Celebration of a Nation

Australia Day, the 1988 Bicentenary, and Citizenship

At some point in the mid-to-late 1970s, my parents became Australian citizens. Considering they both arrived in the country in 1950, this may seem like an excessive delay.

Citizenship was necessitated by a change in the law which, among other things, mandated that immigrants from the UK and Ireland were no longer Australian citizens as soon as they turned up in the country without a return ticket. If mum and dad wanted to keep voting—remember, voting is compulsory in Australia and the country takes citizenship seriously—then they had to be Australian citizens.

This means I’ve experienced one of those traditional, now much-maligned Australia Day citizenship ceremonies, in a period when—although always understated in style—Australian patriotism displayed on the country’s national day was an unalloyed good.

Sprigs of wattle. Certificates of citizenship printed on fancy paper to be framed and hung on the wall. Children from a local primary school singing Waltzing Matilda. The mayor in his hot purple robes and medallion chains reeling off a series of more or less inappropriate gags. Sausages with fried onions, followed by pavlova served on paper plates at long trestle tables. Friends and relatives clutching polyester Australian flags. Kids running around as high as a kite on red cordial. Parish pump politics, small-town patriotic hoopla, all of a summer’s day.

The Poms and Paddies and a lone older central European milled about, shaking hands with much younger immigrants from Vietnam and what was then known as Yugoslavia. The central European, it turned out, was Hungarian. The Nazis had revoked his Hungarian citizenship because he’d been involved in anti-fascist politics before the war. However, given he also rejected Communism, the country’s post-war Warsaw Pact regime had neglected to restore it. AusGov—concerned he was technically stateless thanks to falling through the cracks—was now ensuring he at least had Australian papers.

Even to someone who attended only as a spectator—a small child, say, who’d heard of Australia without yet grasping that she lived there—it was obvious the Australia Day citizenship ceremony was for immigrants. It was, in a real sense, their day.

By the time Australia’s 1988 Bicentenary rolled around, the nation-building aspects of immigration and citizenship remained front and centre, despite sometimes awkward incorporation of Australian Aboriginal motifs.

If you’re Australian of a certain vintage, you’ll remember this advert and others like it.

Australian governments—both state and federal—went absolutely hogwild when it came to the Bicentenary. It was possible to drown in an ocean of memorabilia if you’d caught the collecting bug. Some of it was (and still is) valuable, although of course fools and their money were also readily parted.

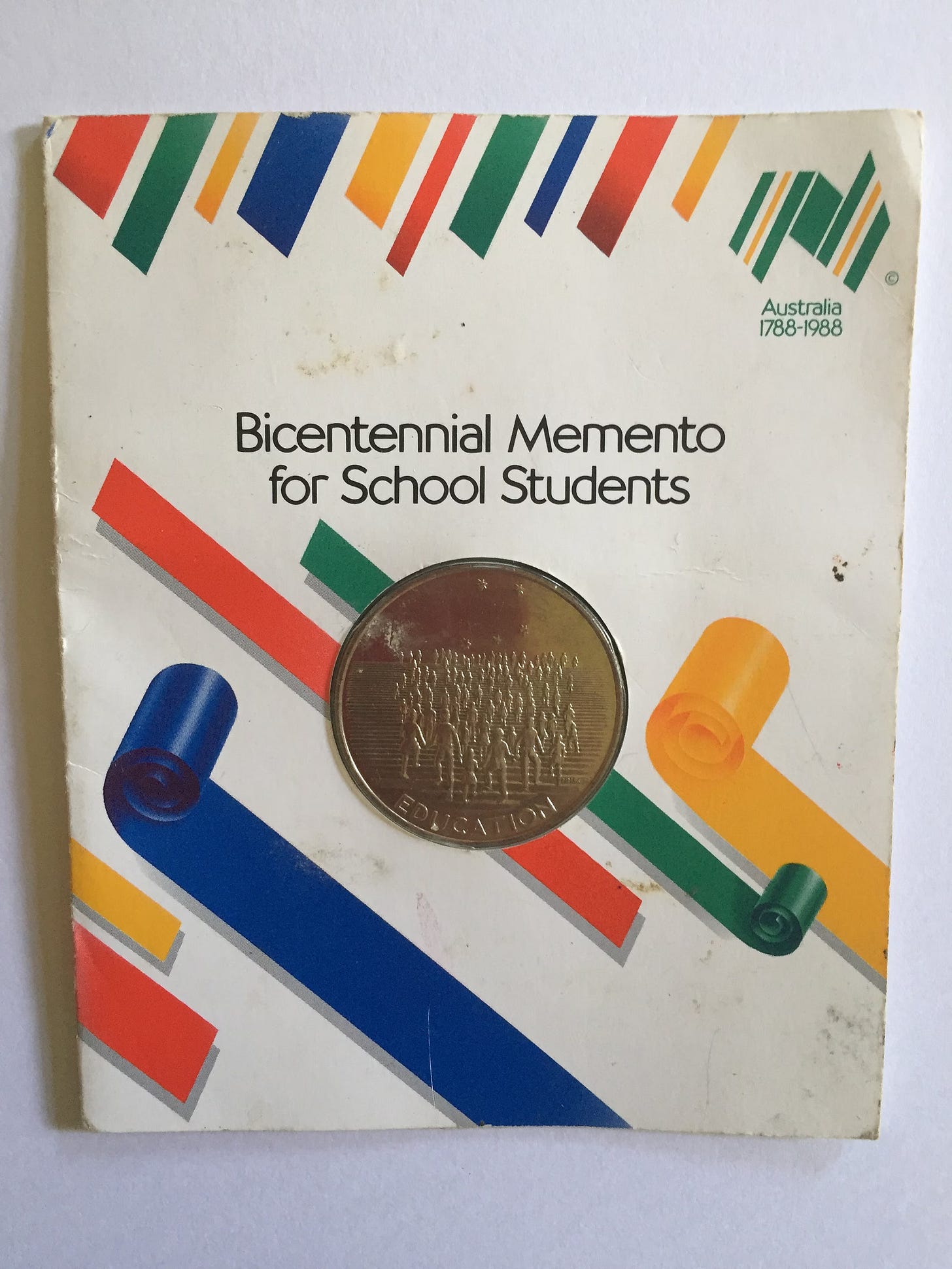

Every schoolkid in the country got one of these (not valuable, I don’t think).

You’ll note the oddly stylised map of Australia on both coins and packaging: it means they were official products endorsed by the Australian Bicentennial Authority.

At the time, there was controversy over the ABA logo, perceived as it was to leave Tasmania off the map. This was an ongoing point of irritation. During the opening ceremony for the 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane, a map of Australia—also with Tasmania left off—had featured heavily.

It’s worth noting that in 1988, the idea of “progress” in Australia was different from that in the US either then or now. Progress meant “economic prosperity and technological excellence”. It did not mean “social progress”. Even now, most Australians don’t tend to incorporate social justice into their politics, at least not automatically. To carry the Australian electorate, anything resembling social justice must draw on one of its older definitions: economic redistribution, collective bargaining in the workplace, good wages.

This was brought home in October 2023’s Voice Referendum, when the electorate resoundingly rejected the importation of US-style social justice politics. I still maintain the result happened in part because the YES campaign did not recruit the unifying uplift that formed such a large part of the 1988 celebrations. In one of my post-mortems on the result, I commented:

Australia Day—the country’s national holiday—was labelled “Invasion Day.” Australia was “occupied.” People who’d immigrated were called “settler-colonials” or just “colonists.” Indigenous Australians (their collective nouns kept changing) were “oppressed.” At first—catching it out of the corner of my eye, busy while life made other plans—I thought this was boiler-plate racism.

I still agree with past Helen’s intuition that Australia Day citizenship ceremonies are for immigrants, and exist to introduce them formally to people already in the country. Meanwhile, most of those people are also immigrants or the descendants of immigrants.

There’s no evidence Australian Aborigines developed the concept of citizenship. Letting activists mess with it via attacks on Australia Day has done little for the cause of national unity, and led many local councils to abandon their Australia Day citizenship ceremonies for reasons that genuinely do look petty and small-minded.

In the form it takes now—throughout the developed world at least—national citizenship has its historical roots in the Roman Republic. There’s no shame in not coming up with citizenship, or democracy (Athens), or the separation of powers (Europe generally), or the representative principle (England, Scotland, France, Poland) or the rule of law (Rome, England).

Anyone can use those things.

At the same time, do remember they were invented by particular people in particular locations in particular historical periods. They’re also good things. They make the countries that use them better places to live. They’re part of how and why the world grew rich. And because other people came up with them first, the rest of us don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

Unlike other material in my piece thus far, the short clip (below) is new, made for Australia Day 2024. Precisely because the Voice referendum result is so recent, its presenter (the Centre for Independent Studies’ CEO Tom Switzer) has to engage in some awkward exposition in the middle.

Switzer’s awkwardness comes from the attempt—which probably did start in 1988, at least officially, with the Bicentennial—to yoke Aboriginal dispossession to Australia Day and yet retain the latter’s historic importance for a wider sense of nationhood. It’s not his fault and, realistically—given the result in that calamitous referendum, which he discusses—we’re now stuck with it.

We’re stuck with it until the losing YES case gets over the referendum result and stops trying to fiddle with Australia Day.

Australia Day is bigger than any one individual or minority ethnic group. And yes, that includes the ones that were there first. It’s important to the country’s national cohesion and—once again, until that utter shitstain of a referendum in October—its ability to avoid the sort of polarisation that is wrecking the US, UK, and EU.

From a distance, then, hope your Australia Day is a good one. If your local council does Australia Day Citizenship ceremonies, go along to support the New Australians there.

I am American ("Californian," to be specific, and yes, there is a difference). I pray that Australia (which I have never physically visited) does not fall victim to the identitarian dogma that is tearing my country apart. It is not even utopian; it is nihilistic.

And even if it were, the people who wish to tear down "the present," however flawed, from its roots, neglect to even think about, much less offer, a coherent, practicable, livable alternative. For this reason, dogmatic utopianism almost always leads to everyday hell. And yes, "the everyday" is the real test.

Michael Oakeshott is an under-appreciated voice, and I will end with his words:

"To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss. Familiar relationships and loyalties will be preferred to the allure of more profitable attachments; to acquire and to enlarge will be less important than to keep, to cultivate and to enjoy; the grief of loss will be more acute than the excitement of novelty or promise. It is to be equal to one’s own fortune, to live at the level of one’s own means, to be content with the want of greater perfection which belongs alike to oneself and one’s circumstances. With some people this is itself a choice; in others it is a disposition which appears, frequently or less frequently, in their preferences and aversions, and is onto itself chosen or specifically cultivated."

On Being Conservative

I certainly hope Australia can avoid the polarization over ethnic identities that afflicts the US, but after seeing the general behavior of its government during Covid, I am not sanguine. But really the whole concept of "indigenous" is absurd. There is not one patch of ground anywhere on this planet whose present-day inhabitants are the lineal descendants, and only the lineal descendants, of the "original" inhabitants. Human beings have been moving around and pushing one another out of the places they inhabit since we first walked upright. Picking a specific date and arbitrarily dividing people as of that date into "indigenous" and "settler" (or some such) is merely ideology, not history.