Cheating for Racists

Affirmative action is morally monstrous

As many of you know, I have a policy of ignoring US politics and culture to the greatest extent possible. I try, instead, to pay attention to Australian politics (because I was born there) and European politics (because I speak two European languages, one fluently and one reasonably well).

However, given I’m employed as Senior Writer for a legally focussed US magazine (Law & Liberty), I’m professionally obliged to note leading SCOTUS rulings, and have read hundreds of them over the years. This doesn’t mean I always write about them, but when I do, I try to do so from a position of knowledge.

To that end, I’m in the process of reading the SCOTUS ruling ending affirmative action in US universities: so far, Roberts CJ’s controlling majority opinion and Thomas J’s concurrence. I’m about to start on Gorsuch J’s opinion, and will also read Kavanaugh J and the dissents.

While I’m a lawyer, I’m not a US lawyer. Although based on the English common law, the US legal system has strayed furthest from its mother. That means the SCOTUS opinion will provide local colour and context so I can write about affirmative action from the perspective of someone legally trained and experienced in two countries that use much less of it.

When I went to university in Australia and then the UK, there was no affirmative action at all. There is some in both countries now, but mainly in employment, not in education. I’ll discuss those changes in my forthcoming piece.

The Australian system was (and largely still is) particularly inflexible. University entrance when I went through was based entirely on scores in standardised tests and results in individual, externally assessed subjects (maths, English, physics etc). Despite its extraordinary sporting achievements, Australia has no history of separate admission for good athletes, or what Americans call “legacies”, something I find completely crackers. Why should you get into university more easily because your parents went there? Honestly, just fuck off.

It’s for this reason—when I first encountered American affirmative action, widespread in that country since 1973—the first sentence to fly out of my mouth was “people who get into university like this are cheats”. Like most Australians of my vintage, I’d played a lot of sport as a kid. And cheating is just about the worst thing you can do as a player. Recall the country’s reaction to the cricket-ball-tampering-sandpaper scandal.

To that end, I should warn readers—in advance of my piece for Law & Liberty—that I haven’t really changed the view I formed at 17.

If you get a higher mark in an exam by, say, secreting a list of formulae in your sock and surreptitiously using it when you can’t remember how to do indefinite integrals— and thereby get a better result—you are a cheat.

You’re still a cheat if you don’t do better, too. Your cheating simply didn’t pay off.

If you use your ethnicity to get into a prestigious university when your results would not otherwise be good enough to get you into that university, you are a cheat.

Yes—as SCOTUS makes clear—the universities built and maintained this pernicious system. But every single student wrongly admitted thereby is a cheat.

You ask, presumably rhetorically, why you should get into university more easily just because your parents went there? It turns out that there is a simple reason: most private universities have traditionally raised the bulk of their finances, not from tuition, but from alumni donations. It is therefore very much in the university's interest to keep their alumni loyal. They do this in a number of ways, including regular mailing, sports success... and admitting the children of alumni.

It has been found, therefore, that alumni donations regularly increase during their children's high school years, in hopes of making it that much more likely for those children to be admitted, and it is largely assumed (although I've seen no data) that it is specifically the children of alumni who are large donors who have the highest chance of admission.

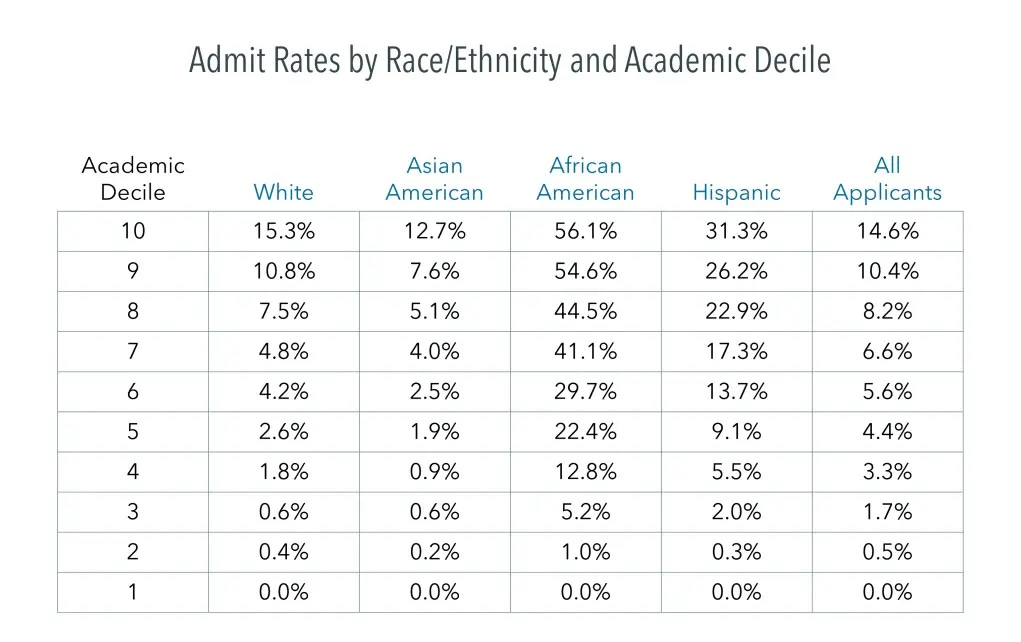

As an American who studied at the Australian Graduate School of Management in Sydney, I applaud your perspective and quick analysis. I think you should explain the table to the mathematically challenged who will not quite get what the - very powerful - point the table makes.