Class and the state

Surplus drives history: states create surplus

This is the third essay in Lorenzo from Oz’s series on the strange and disorienting times in which we live, and as with the previous two, the ensuing conversation has been extraordinary. This time, Josh Slocum responded in the podcast (vodcast, really, with astonishing production values) that goes with hisDisaffected Newsletter. You’ll need to watch to get the skinny.

Other things are also in train. I have activated paid subscriptions, and a number of you have put your hands in your pocket so money goes into Lorenzo’s pocket. Do be aware, however, that this substack will always be kept free for everyone. I’m vain enough to think that Lorenzo’s ideas are important enough not to go behind a paywall. I want people to read them. So does he.

That means providing benefits other than paywall-dodging for people who donate.

Founders who pay USD$120 will get a free copy of one of my novels (please choose one and write to me with an address; you know who you are). Paid subscribers generally will get exclusive zoom chats with me, Lorenzo, and — if there is enough money in the tip-jar — other writers I publish.

Note: I have decided against setting up the “Buy Me a Coffee” tip-jar facility, as according to the Free Speech Union’s briefing on the speech-friendliness of various payment processors and crowdfunding platforms, it rates a lowly 3/10 — only PayPal and Patreon are worse — and has become notorious for pulling the rug out from under people for wrongthink.

This means I will have to come up with an alternative for those of you who wish to make tips in the traditional “blogging” way. Please bear with me.

Once again, the publication schedule for Lorenzo’s essays is available here, and will remain pinned at the top of my substack throughout the publication process. I’ll also link each essay there as it’s published, so it becomes a “one-stop-shop”.

Lorenzo is on Twitter @LorenzoFrom. I’m on the Bird Site @_HelenDale

Both of us will tweet each essay as it’s published. Do subscribe below so that you don’t miss anything, and help spread the word.

Note: at the end of each essay, you’ll find a detailed bibliography and suggestions for further reading.

A key advantage mercantile societies have over the alternatives is that commerce naturally tends to eliminate inefficiency, as it releases potential income. Conversely, bureaucracy naturally tends to entrench inefficiency. The more resources the bureaucracy consumes, the more resources accrue to bureaucrats. Hence the economic stagnation from multiplying inefficiency to which command economies are so prone, compared to the dynamism of mercantile societies.

When academics teach Marxist analysis, they are teaching false claims about commerce. They are also teaching false claims about class, the state, and surplus.

Surplus delusions

That Marxist regimes are unrelievedly tyrannical is a direct result of Marx’s theory.

According to Marx, surplus is produced via ownership of the means of production extracting surplus value. And it is true commercial activity can absolutely generate income above subsistence (that is what surplus is). In modern mercantile societies, profit share is about 15 per cent of GDP.

Yet commercial activity has never been the dominant generator of surplus. In any society ruled by a state, the dominant surplus generator has been the state itself, via its taxes.

In developed mercantile societies, the tax share is 35-50 per cent of GDP. Yes, those taxes are extracted from highly productive societies, well able to generate incomes far above subsistence. Nevertheless, it is normal for taxation to be the dominant generator of surplus in societies ruled by a state.

It’s true that the scale of modern taxation is unprecedented. This is mainly thanks to the development of modern firms, whose documented mass employment make income much more transparent to the state and so an excellent tax-collection point.

What the state can document (or is otherwise visible to it), it can tax. What is not documented (or is otherwise not seen), not so much. But, in all societies with a functional state, the state is the dominant generator of surplus.

The only significant exception to this is slavery, as slaves are not only markers of power and prowess for their owners. Slavery also enables extraction of surplus without a chiefdom or state.

Slaves have no kin encumbrances, for they are so dominated they are stripped of any connections that their master need respect. Hence the ability to turn them into property, force them onto subsistence incomes, and extract a surplus from them.

Although seizing and enslaving captives was ubiquitous in human societies, stateless societies were limited in how much they could engage in slavery. The mere existence of slaves did not create a tax base. For that, stored food was necessary.

Farming and pastoralism

Property is ubiquitous in human societies. Every single human society has some concept of property, because having simple-to-operate conventions that determine who gets to decide about a thing makes it so much easier to manage material things.

Property is something law (if you have it) deals with, yet law is not required for property — for mutually acknowledged possession granting the right-to-decide — to exist. Indeed, every black market on earth has property transactions entirely without legal warrant.

Every human society has property. Since the evolution of our species, only a tiny minority of all the human societies that have existed have created significant surpluses. Property does not, in itself, create surplus.

There is a claim that developing farming means generating surplus. This is also mostly not true. What more food production mainly means is more babies.

Farming was first developed by women, as they dominated the gathering of plants. Unless and until societies shifted to using ploughs, women dominated farming labour.

It takes less skill, and involves less day-to-day risk, to be a successful farmer than a successful forager. Farming means children become more useful more quickly. Thus, farming reduced the cost of raising children, including the costs of supervising them (something sedentary living also did), so mothers could have more of them.

Farming not only made smaller (and so more numerous) human niches sustainable. It also expanded the number of such niches via expanding food production. More food => more niches is straight Malthusian population dynamics that we can see throughout the biosphere.

The only way to reliably extract, and so generate, a systematic and substantial surplus was to take food before it turned into supporting more babies. Which is what the taxing activity of the state does.

Such taxing requires, in the first instance, stored food, so that extracted resources can be transferred and stored to support the apparatus of the state. This is why states only evolve in places where there are seasonal crops, which thereby generate stored food.

The stored food (and seeds) of seasonal crops also create an elevated protection problem. From this arises the paying-for-protection spiral that ends in chiefdoms and states.

Taxing labour service and trade (the dominant other ancient tax sources, apart from mines) are dependent on there being sufficient stored food to support the taxing apparatus and those providing labour. Even mining on any scale usually requires stored food.

Regions with no seasonal crops, so no stored food, do not generate states, or even chiefdoms. There is no start-up tax base with an intensified protection problem. For instance, New Guinea had no seasonal crops generating stored food, hence its millennia of farming without states or chiefdoms.

How one can examine such monumental constructions as the Great Pyramids, Angkor Wat and the Great Wall(s) of China and not appreciate that states dominate the extraction of surplus? The capacities of societies with states are far greater than stateless societies precisely because states so dominate the extraction and creation of surplus (and engage in the pacification necessary to generate and sustain such surplus).

Pacifying surplus

Subsistence drives life, but surplus drives history. The extraction and creation of surplus drives the expansion of human capacity.

While gift and trade networks are ancient (possibly about as old as Homo sapiens), to have significant levels of commercial activity depends on, and is enabled by, the pacification effects of states. Indeed, the pacification of society by chiefdoms and states was such a dramatic change in human affairs that it shows up in the genetic record.

After population surges from the development of farming and pastoralism, competition between kin-groups became so vicious that only about 1-in-17 male lineages made it through what is known as the Neolithic y-chromosome bottleneck. It was only the pacification efforts of chiefdoms and states which brought this harrowing of male lineages to an end, though such harrowing continued to some degree in pastoralist societies.

Female lineages were largely unaffected, as women were clearly appropriated by the winning males. In contrast to farming and pastoralist societies, conflict between foraging populations is much more likely to lead to “kill them all” complete population replacements, as foraging societies have little capacity to absorb extra mouths.

Kin-groups enabled the creation of highly effective aggression by warrior-teams, with women, land and animal herds being spoils to fight over. The development of chiefdoms and states enabled the techniques of exploitation (via tribute and taxation) to catch up and surpass these techniques of aggression. Chiefs and rulers pacified to protect their taxpayers (and so their revenue base).

Pacifying to tax

Rather than — as competing kin-groups did (and pastoralist kin-groups did particularly effectively) — kill or enslave rival men and take their women, one could instead protect-and-tax men and their families. Rulers thereby lived off (in a sense farmed) people who themselves farmed plants and animals. Such living-off included fostering, and then taxing, trade within pacified domains.

The importance of state pacification efforts to levels of commercial activity has not gone away. The first great era of mass globalisation — from the invention of steamships and railways in the 1820s to the outbreak of war between the European Great Powers in 1914 — was based on the Royal Navy’s pacification of the world’s oceans. Just as the post-1945 mass globalisation has been based on the pacification of the world’s oceans by the US Navy.

In contemporary societies, where do states pacify (i.e. police) least? Localities that are fiscal sinks. That is, localities that cost more in welfare and other expenditure than they return in tax revenues (or are so undocumented they generate little tax revenue). Such fiscal-sink localities being under-policed, and so suffering more crime, is a pattern one can see very strongly across the shanty-towns of the developing world (especially in the Americas) and in the “distressed urban localities” of the US and France and somewhat more weakly elsewhere in Europe.

This sets up interactive processes. The more densely populated a locality, the more interactions with those who are violent. As executive function (and control) is highly heritable and socially sorted, there are more potential committers of violence in welfare-dense/poor localities.

Consequently, the incentive to provide effective policing services is lowest at the localities where the need for effective policing is highest. The less effectively policed is a locality, the more illegal activities will occur there, both of which lead to the more violence. States, and what they do (or don’t do) really are fundamental to the ordering of societies.

Imperialism is territorial expansion of pacifying-to-tax. It is a fable of empire that empire represents, or serves, the interests of the core region from which the empire was built. The core interest empire serves is the state apparat itself, including the ruler atop it.

Yes, various interest groups may be enlisted by, or seek, the spoils of empire, or be flattered by its rhetoric. Yes, empires foster trade, but for the revenue this trade provides to a state apparat. The more autocratic the state, the more it is the state apparat and the ruler any empire serves: the less any spoils have to be shared.

Even that most mercantile of empires, the Venetian, is not really a counter-example. For in the Serene Republic the citizen-nobles were, very deliberately, deeply entwined with the state apparat.

All the countries that lost their maritime empires after 1945 proceeded to get richer, suffered little social disruption and had their democracies strengthened. Ironically, some of those who most propagate fables of empire as grand social projects for entire societies—rather than projects of the state apparat—are themselves critics of empire. They buy into such imperial fables so as to either to elevate their rejection of empire or to serve other agendas.

Creating class

As states dominate the extraction of surplus, they also dominate the creation of class structures. Tax-extracting (and so surplus-creating) states also control access to said surplus.

This state domination of the creation of class structures is nowhere more clearly demonstrated than in revolutionary Marxist states. The revolutionary vanguard-capital elite seizes control of the state, atomises society and creates a class structure to suit the new regime’s ideology and interests. Every Marxist state represents directly and obviously state-created class structure.

Yet again, the notion that Lenin somehow perverted Marxism fails. As private commerce was deemed by Marx to be the source of oppression and exploitation — with modes of production driving social structure — there was no need to pay attention to millennia of thought about how to manage state power. For Marx, all production can be concentrated in the state, if it is controlled by the correct class, motivated by the correct purpose, with the correct historical role.

Leninism, in all its derivatives, operationalises (and speeds up) Marxism in accord with the logic that oppression and exploitation is a result of private ownership of the means of production, and that the state “reflects” modes of production rather than being a fundamental structuring element of society. So, a proletarian state can safely encompass all major production.

As Marx states:

Social relations are closely bound up with productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces men change their mode of production; and in changing their mode of production, in changing the way of earning their living, they change all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist.

The Poverty of Philosophy, (1847) Ch.2.

The state is reduced to an instrument of class:

… the bourgeoisie has at last, since the establishment of Modern Industry and of the world market, conquered for itself, in the modern representative State, exclusive political sway. The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.

The Communist Manifesto, (1848) Ch.1.

The notion that state apparats are inherently agents of their society, or parts thereof, is ahistorical nonsense. Even the most autocratic rulers struggle to turn the state apparat reliably into their agents. One of the advantages of Parliaments for medieval Christian rulers was that they provided feedback about their own officials.

This is why all manorial authorities (knights, nobles, the Church, kings) supported the Church’s measures against kin-groups, as it meant kin-groups could not compete against their authority. Kings even gave up their concubines (secondary wives able to also provide heirs). Suppression of kin-groups via the whole “Christian package” (single-spouse marriage, no consanguineous marriage, no adoption, female consent for marriage, individual wills to break kin-group control of property transmission) meant that kin-groups did not colonise their instruments of rule.

Given the way kin-groups colonised the Irish Church, frustrating Papal control, the medieval Papacy had reason to be very keen on suppressing kin-groups. Unfortunately for the medieval Papacy, pastoralist Ireland lacked manors. There was not the same shared interest with the landholding warrior elite in suppressing kin-groups. Clan chiefs in particular were not interested. (When, in 1688-9, it came time to choose between supporting the Catholic clan chiefs or the clan-suppressing, Protestant British crown, the Papacy chose the latter.*)

Forcing the state apparat to be full agents of a wider society has been a constant struggle across centuries of European (and Eurosphere*) history. Yet the notion that the state is a manifestation of society, rather than a fundamental ordering element of society, at least implicitly underpins a lot of social science.

As I’ll discuss in later essays, societies never achieve full and final victory in the struggle to force subordinate agency and accountability on the state apparat. Not even in the most stable democracies.

Lenin advocated “speeding up” the process of social transformation. Which meant that he—as he freely stated—applied the Jacobin model of politics to Marxism. Politics unlimited in ambit (so every aspect of life is politicised) and unlimited in means.

But Marx was an advocate and theorist of revolution; he was an advocate of handing all production to the proletarian state, of liquidating exploiting classes. Operationalising the intentions and implications of Marx’s thought was simply Lenin being a practical Marxist, just as collectivisation proletarianised the peasantry in accordance with Marx’s failure to understand commerce.

This devalued both the patterns of discovery and local information inherent in successful peasant farming, while homogenising people within simplistic categories from the top down. It also devalued dispersed discovery and distributed information.

All such collectivisation devalues and obscures the discovery and management of individual differences in human enterprises. Differences that “blank slate” views of humanity deny but any effectively functioning system must manage and that evolution tells us are inevitable.

The value of constraints

That Marxist parties operating within the constraints of liberal democracies operated within those constraints tells us about the value of those constraints, not about Marxism. These are constraints that make it possible to force the state apparat into being an agent of the wider society.

The notion that Marxists in power without those constraints is not authentic Marxism is as ridiculous as the notion that the Nazism in power without those constraints is not authentic Nazism. Breaking those constraints, both the wish to (which both movements shared), and what they did when those constraints were broken, are revelatory of the nature of the two ideologies.

In the next essay, I look at the paradox at the heart of every polity: we need the state to protect us from social predators, but the state itself is the most dangerous of social predators. A paradox that can never be solved, just managed more or less badly.

*That the Pope in question, Innocent XI (r.1676-1689) was very hostile to Louis XIV (r.1643-1715) was also a factor.

**Eurosphere: European societies plus societies that acquired a sufficient proportion of the population (particularly elite population) of European origin (the neo-Europes of the Americas and the Antipodes plus Siberia) so that their cultural and institutional heritage is predominantly of European origin.

References

Books

Catherine M. Cameron, Captives: How Stolen People Changed the World, University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

David Frye, Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, Faber & Faber, 2018.

Paul R Gregory and Valery Lazarev (eds.), The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag, Hoover Institution Press, 2003.

Michael Mitteraur, Why Europe? The Medieval Origins of its Special Path, trans. Gerard Chapple, University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2010.

K.W. Nicholls, Gaelic and Gaelicized Ireland in the Middle Ages, Lilliput Press, [1971, 2003], 2012.

Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study, Harvard University Press, [1982], 2018.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, Yale University Press, 1998.

James C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale University Press, 2017.

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, The Bodley Head, 2010.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

Articles, papers, book chapters, podcasts

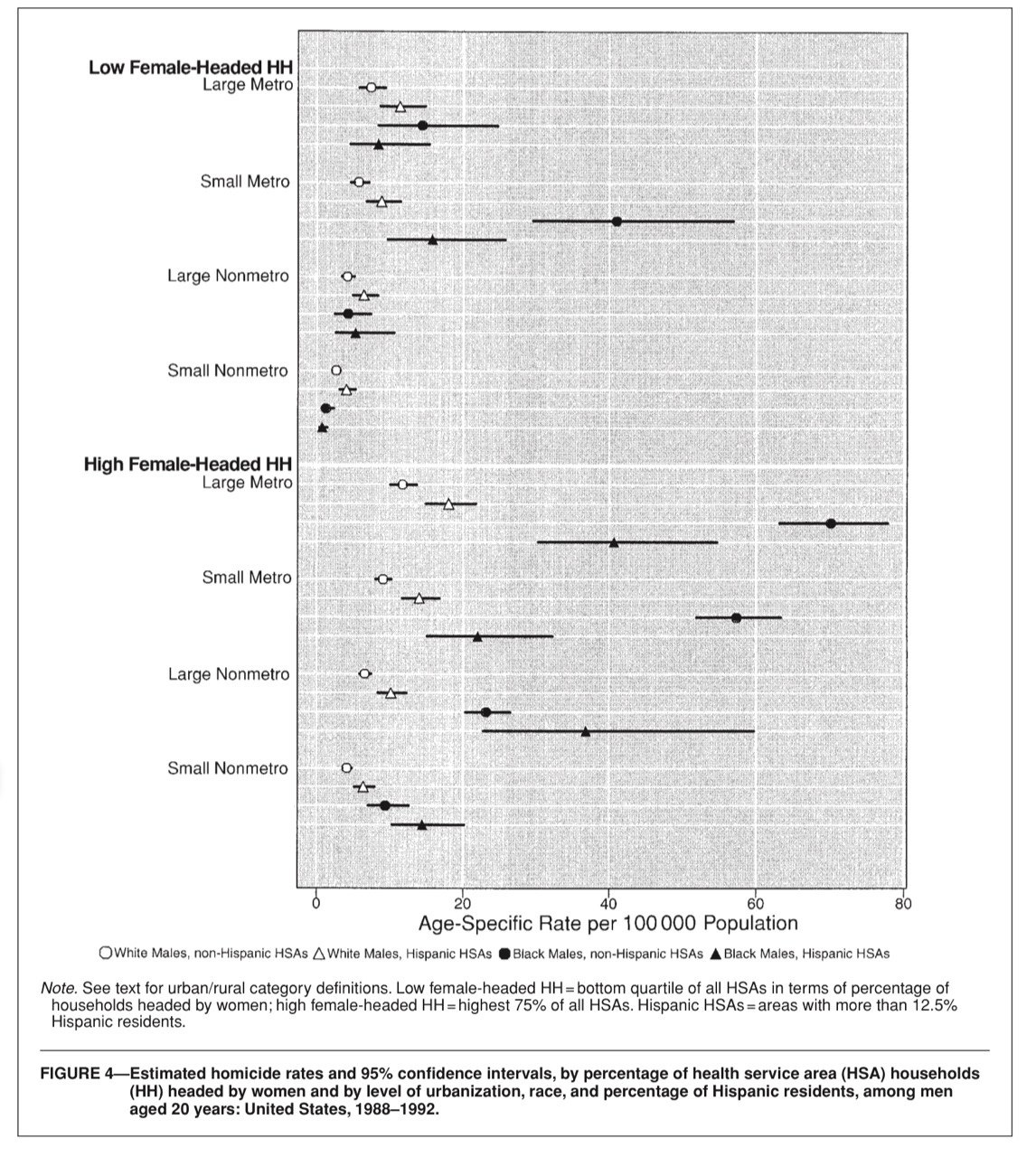

Catherine Cubbin, Linda Williams Pickle, and Lois Fingerhut, ‘Social Context and Geographic Patterns of Homicide Among US Black and White Males,’ American Journal of Public Health, April 2000, Vol. 90, No. 4, 579-587.

Laura E. Engelhardt, Daniel A. Briley, Frank D. Mann, K. Paige Harden Tucker-Drob, ‘Genes Unite Executive Functions in Childhood,’ Psychological Science, 2015 August, 26(8), 1151–1163.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, Vol.85, No.1, Feb. 1977, 59-77.

F. A. Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society,’ American Economic Review, Sep. 1945, XXXV, No. 4, 519-30.

Henrik Jacobsen, Kleven Claus, Thustrup Kreiner, Emmanuel Saez, ‘Why Can Modern Government’s Tax So Much? An Agency Model Of Firms As Fiscal Intermediaries,’ NBER Working Paper 15218, August 2009.

V.I.Lenin, ‘One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: (The Crisis In Our Party),’ February-May 1904, published in book form in Geneva, May 1904.

V.I.Lenin, ‘Can “Jacobinism” Frighten the Working Class?,’ Pravda, No. 90, July 7 (June 24), 1917.

Karl Marx, ‘Value, Price and Profit’, in The Essential Left: Five Classic Texts on the Principles of Socialism, ed. David McLellan, Unwin, [1960], 1985, 51-106.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency, and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, June 2017, 111, 3. 622-636.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, ‘The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?,’Journal of Political Economy, April 2022, 130, 1091-1144.

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 2018, 9:2077.

The modern Left has forgotten about class. No, I have never been a Marxist - when my father explained it to me when I was 8, I said, “People don’t work like that. Even chickens and cows don’t work like that.” Also I know too many ex-Soviets to have a bar of Marxism! But I do think class is really important in analysing social dynamics.

As an outsider (Brit/naturalised Aussie) in Ireland, Ireland still appears - or did appear, 20 years ago, less so now - very tribal. "Kin groups" and "hereditary constituencies" still dominate even national politics to an extent I found astonishing coming from Australia (only other country I've voted in). My reading informs me that some recent Irish tragedies e.g. Magdalen laundries (still not fully acknowledged by the whole community or full restitution given, if it ever will be) were in reality motivated by the concept of keeping land inheritance 'within the (legitimately acknowledged) family' rather than Catholic prudery, which is the official 'explanation'.