Feminisation has consequences: I

The evolutionary novelty of abandoning presumptive sex roles

This is the fourteenth piece in Lorenzo Warby’s series of essays on the strange and disorienting times in which we live. The publication schedule for Lorenzo’s essays is available here.

This one can be adumbrated thusly: Men and women are not only physically dimorphic but cognitively dimorphic. This reality has major social effects and policy consequences.

Housekeeping: This is the tip link; you can tip as much or as little as you like. I have complete control over tips, not substack.

Do remember this substack is free for everyone. Only contribute if you fancy. However, if you put your hands in your pocket, money goes into Lorenzo’s pocket.

This, meanwhile, is the subscription button, if that’s how you prefer to support Lorenzo’s writing:

If something is found in all human societies, it counts as a human universal.

In every culture in which it has been systematically studied, it has been found that boys and girls segregate into same-sex groups and engage in different forms of play and social behaviour in these groups. (Geary et al 2003.)

If something is observed in every human society, it will have a fair degree of innateness to it. Indeed, as societies become more prosperous and more liberal— meaning people occupy larger and less constrained social niches—innate factors become more salient because environmental factors are less constraining.

As evolutionary psychologists John Tooby and Lena Cosmides write:

The assertion that “culture” explains human variation will be taken seriously when there are reports of women war parties raiding villages to capture men as husbands, or of parents cloistering their sons but not their daughters to protect their sons’ “virtue,” or when cultural distributions for preferences concerning physical attractiveness, earning power, relative age, and so on, show as many cultures with bias in one direction as in the other.

Culture does explain some human variation. We are the most cultural species because we have the biological adaptations to be the most cultural species. And human cultures vary, as the above indicates, within the parameters of those adaptations.

There is nothing scientifically surprising about human children sex-segregating while displaying sex-differentiated play and social behaviour.

We live in an age where mountains of bullshit—such as on sex and gender matters—are regularly created within academe out of molehills of truth. Societies have often constrained women, for example, but that fact does not support the huge theoretical edifice constructed above it. This has happened because reality tests across the academy are so weak.

Some elementary facts about the human condition therefore need to be reiterated.

Dimorphic realities

We are a sexually reproducing species, with two sexes (i.e. producers of two different types of gametes, one small and motile, the other large and sessile) which thus have different reproduction strategies. This leads to various forms of sexual dimorphism in our species.

One is dimorphism in shape. Male and female Homo sapiens are more shape-dimorphic than any of our primate cousins. This is partly because female Homo sapiens have higher fat content in their bodies, so they have the stored calories to—if necessary—support two energy-hog human brains: their own and their infant’s.

Regarding size-dimorphism, while adult human males average about eight per cent taller and about 13 per cent larger than adult human females, that is actually a relatively low level of dimorphism by primate standards. For instance, adult male gorillas are about twice the size of adult female gorillas, a fairly common level of disparity in harem species.

A much more significant dimension of dimorphism in Homo sapiens is that adult human males average twice the lean upper body mass of adult human females. So, females average about 52 per cent of the upper body strength, and about 66 per of the lower body strength, of males.

This difference in strength leads to different patterns of physical aggression. That this difference is far more strategic than innate can be see from the fact that adult women are at least as likely to engage in physical aggression against a systematically physically weaker group of Homo sapiens (children) as are men. Similarly, male willingness to engage in physical aggression is profoundly affected by whether they are married and whether they are fathers.

Hormonal differences between men and women are much more about managing differences, including differences in reproductive strategies and risks, than in generating patterns of aggression or other behaviour. Hormone levels respond in part to individual circumstances. People who take testosterone they have not evolved to or been socialised to manage can be dangerous to themselves and others.

Adult humans also show high levels of cognitive dimorphism. Using the 15 personality traits* that are aggregated together to form the Big Five (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism), approximately 80 per cent of us have a pattern of traits that do not occur in the other sex. This does lead to differences in patterns of behaviour, including occupational and other choices.

These choices respond to circumstances. For instance, across the C20th, the proportion of women entering professions rose and fell with average age of marriage. So, as the average age of marriage rose in the first part of the century, the number of women entering professions rose. As the average age of marriage fell in the middle part of the century, the number of women entering professions fell. When the average age of marriage then rose again (and the number of children kept falling), so did the number of women entering professions.

Women also tend to avoid occupations where there is a high rate of skill obsolesce, favouring occupations where one can leave and enter with a break, something much more compatible with pregnancy and nursing small children.

The cognitive dimorphism between men and women means that if one entrenches what men do on average as a benchmark for women, one is likely to set up a disconnect for many women between aspiration and experience. It also means that any “blank slate” ideology is likely to fail to promote human—particularly female—flourishing. It’s notable that in the period since the Sexual Revolution (across the developed world), masculinised sexuality—where we replaced a norm of sex-within-commitment with sex-as-cathartic-release—women have fallen behind men in average happiness.

Pushing what men do as the benchmark for women either eliminates the differences between men and women from consideration, or requires active measures to suppress differences between men and women. In particular, it will tend to devalue motherhood, which is distinctively female.

Evolutionary novelty

That—even in foraging societies—a human child represents an almost 20-year investment creates fundamental patterns in all human societies. Most notable is the transfer of risks away from childrearing and the provision of resources to childrearing.

Such transferring of risk is part of why we are such a cognitively dimorphic species. Homo sapien males are extraordinary among mammals in how much they invest in their offspring. This creates an unusual level of convergence in reproductive strategies between males and females. Nevertheless, that there are different potential reproductive costs—while convergence is based on systematic transfer of risks—clearly drives a cognitive dimorphism too high to be anything other than a pattern of adaptation for reproductive success.

In Homo sapiens, female ornamentalism (prominent breasts, curved figure, delicate features) evolved to attract males willing to accept the transfer of risks to them and to commit to the joint decades-long project of raising children. Conversely, male ornamentalism (beards, muscularity, deep voice, height) is mainly to intimidate other males. Only human penises being unusually large among primates is about impressing women.

This pattern of transferring risks and resources has also meant that all human societies, until very recently, had presumptive sex roles.

Sex is a matter of biology, of strategies of reproduction. Sex roles are the behavioural manifestation of sex. Having sex roles is common in sexually reproducing species. Gender is the cultural manifestation of sex. We are the only species that is sufficiently cultural that we can usefully speak of the cultural manifestations of sex.

So, if one is going to transfer resources to, and risks away, from child-rearing then one is going to have sex roles. How rigidly defined sex roles are has varied enormously between societies. In particular, the role of father tends to vary across cultures far more than the role of mother.

We are mammals whose children take decades to reach full adulthood. The biological constraints on successful motherhood are strong.

Fatherhood—as distinct from biological paternity—is a social construction. It is why we have marriage. It is why human societies perennially suppress short-term mating (casual sex) to protect long-term mating (marriage). This ensures there is male investment in our biologically expensive children.

If, as in the case of the Mosuo of China, fatherhood was traditionally not a socially recognised relationship, then unclehood, a mother’s brothers, provided the male investment. There is far more cultural variation in fatherhood than motherhood.

We have evolved to be a pair-bonding species across thousands of generations. Hence, fatherlessness imposes costs on children that extend into adulthood. As does single-parenthood generally.

Developed democracies have increasingly replaced the providing husband-and-father with the providing state. Both choices have their costs and benefits. It is conspicuous that higher socio-economic classes have stuck to married father-and-mother pattern while those lower down have ever higher rates of single parenthood.

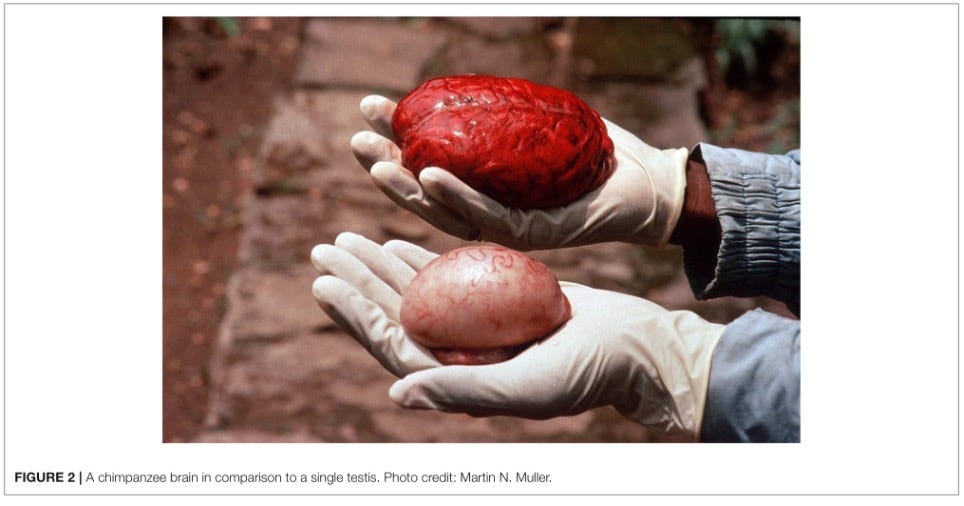

Some people dispute that we are a pair-bonding species. However, we don’t have enough size-dimorphism to be a harem species and the testes of Homo sapiens males are too small for us to be a female-sharing species.

Our chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus) cousins are female-sharing-among-group-of-males species. Hence, their males have evolved large testes so as to spurt aside the sperm of the previous male to mate with a female and have enough to not be all spurted aside by the next male to do so. We do not have that adaptation.

Some have argued that our physical dimorphism suggests we are a (mildly) polygynous species. Leaving aside the unusual gerontocratic polygyny of Australian Aboriginal cultures (likely a learning-transfer mechanism for landscapes with a lot of hidden dangers), the level of polygyny in foraging societies is low. The transfer of risks away from, and resources to, child-rearing seems a much more likely explanation for the various forms of dimorphism among Homo sapiens as it operated on all mating pairs.

All cultures, foraging, farming, and pastoralist, have presumptive sex roles that flow directly from transferring risks away from, and resources to, child-rearing.

In foraging cultures, males dominated riskier hunting and gathering (e.g. raiding bee hives for honey). Females did what they could do with kids in tow. This meant that men dominated the provision of food: particularly protein, particularly to children.

Women have been documented doing such hunting, but only if they didn’t have children in tow. For instance, they are not mothers, all their children are adults or someone else is minding the kids. This is the same pattern as women writers, artists, and intellectuals in all civilisations until the C20th.

In horticultural (hoe-farming) societies, women often dominate the provision of food as hoe-farming can be done with kids in tow. In such societies, one can have very high levels of polygyny as women are net contributors of food (and may well own the land). In plough societies, men usually dominate farming and own the land, as you cannot plough while minding kids.

In pastoralist societies, men own the herds as minding large animals is also not a kids-in-tow activity. In steppe pastoralist societies, the men were often away, so the women were armed and owned the dwellings.

Indeed, whether men were likely to be away was one of the factors most likely to raise the status of women. First, it often leads to armed women, which raises their status. (It is not smart to alienate a women who can kill you at 300 paces; women were often archers.) Second, women have to manage assets, which also raises their status, their accepted range of roles and actions.

Steppe pastoralists, Celtic societies, Norse and Germanic societies, Sparta and Rome were all relatively gender-egalitarian societies for precisely the “men were often away, so women managed assets” reasons (although Romans found warrior women horrifying when they encountered them in Germanic and Celtic cultures).

They were not, however, feminised societies. Whether a society is gender-egalitarian is a completely different issue from whether a society is feminised. That is, whether female patterns of aggression, association, emotionality, and preferences are increasingly salient.

Human societies have typically put considerable effort into creating effective male teams. Pastoralist societies either are, or become, patrilineal kin-group societies precisely so one gets teams of related male warriors who are raised together to defend their highly mobile herds. The effect is particularly strong in the Middle East, where there is a great deal of cousin marriage within kin groups, so that wives are not outsiders and daughters breed new warriors for the kin group (rather than someone else’s kin group).

Matrilineal kin-group societies have the problem of males marrying-in and so being unrelated. In that case, male ritual societies became key male-bonding mechanisms.

All of this means that men (the male expression of Homo sapien genes) evolved to be more cognitively oriented towards forming teams than women. To being in groups of individuals acting in various roles for some common purpose, such as hunting large animals, protecting the group, or attacking other groups.

Men are cognitively and hormonally structured for quicker reactions, find it easier to establish and maintain stable hierarchies, to operate in larger groups, to focus on functional roles, and to create and use tools and technology, than women. Women tend to focus much more on managing and investing in emotional commitments.

Building teams can often involve a fair bit of “ragging” as members test each other out. If I say outrageous things to you, will you still support me? If I push, will you fold under pressure? This pattern often becomes more intense the greater the risks with which the team has to deal.

This encouraged the suppression of emotions, save those which helped team functioning. Status often come from how well one engaged in team behaviour. The love of physical play, of sport, and of team versions of both, fits in with this.

As psychologist Rob Henderson puts it:

Men bond by insulting each other and not really meaning it; women bond by complimenting each other and not really meaning it.

Homo sapien males are quite likely to have lower-status friends. You never know when you might want them on your team. Homo sapien females are much less likely to have lower-status friends, as they are not likely to be worth the emotional investment.

The transfer of risk led to a strong pattern in human societies of male-dominance. Human males are both physically stronger and cognitively structured to be the solidarity sex. This is something that made it easier to enforce male dominance in many societies: to make public authority presumptively male. That is, for the society to be patriarchal.

The least patriarchal of the medieval-and-after civilisations (Christian Europe) still functioned by having male and female domains. The female domain (presumptively running households and society while men ran politics and business) was, however, by the standards of contemporary civilisations unusually publicly extensive. There was none of the sequestering of women regularly seen in polygynous plough societies and there were commercially and politically active women.

Men tend to be oriented towards status through the prestige of competence and successful risk-taking. As part of transferring risks away from child-rearing, women tend to be oriented towards status through the (protective) propriety of conformity-focused adherence to norms.

Being oriented towards teams, solidarity and prestige meant that men are typically the systems-and-rules sex. The main way male physical and sexual incontinence has been restrained historically has been by other males enforcing rules and systems. Men have perennially had women that they wished to protect: wives, daughters, sisters, mothers.

An advantage here is that male-typical aggression—thumping someone—does not scale up except via gangs and wars. (Though threats of violence do.) Systems and teams can be deployed to break up—or otherwise restrain—gangs. The pacifying actions of states are based quite fundamentally on systems and teams.

Women are also more primed to seek connections based on emotional support as signs of commitment, to more emotionally-intimate relationships specifically oriented to respecting others’ feelings and providing long-term individual support.

The delicacy of female facial features makes it easier to express emotion. It is often more culturally acceptable for women to express a wider range of emotions than it is for men.

Female friendships are typically based on mutually observed and respected emotions. This can make female friendships very intense, but it can also make female groups unstable.

Hence human females (and male sissies) create cliques while human males (and female tomboys) create teams. You can see these varying teams-and-cliques patterns in any schoolyard.

As presumptive sex roles vanish, the different cognitive and interaction styles of men and women are mashed together in workplaces. If a process of feminisation ensues, then teams will be undermined compared to cliques, prestige will be undermined compared to propriety, female emotional incontinence will become more prominent (even valorised).

The next essay explores the downsides of feminisation.

* Warmth, Emotional Stability, Assertiveness/Dominance, Gregariousness/Liveliness, Dutifulness/Rule‐Consciousness, Friendliness/Social Boldness, Sensitivity, Distrust/Vigilance, Imagination/Abstractness, Reserve/Privateness, Anxiety/Apprehension, Complexity/Openness to change, Introversion/SelfReliance, Orderliness/Perfectionism, and Emotionality/Tension.

References

Books

Roy F. Baumeister, Is There Anything Good About Men?: How Cultures Flourish by Exploiting Men, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Joyce F. Benenson with Henry Markovits, Warriors and Worriers: the Survival of the Sexes, Oxford University Press, 2014.

Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, The Truth about Cinderella: A Darwinian View of Parental Love, Yale University Press, 1998.

Sir John Glubb, The Fate of Empires and Search for Survival, William Blackwood & Sons, 1976, 1977.

Jemina Olchawski, Sex Equality: State of the Nation 2016, Fawcett Society, January 2016.

Louise Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century, Polity Books, 2022.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Emmanuel Todd, The Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems, (trans. David Garroch), Basil Blackwell, 1985.

Articles, papers, book chapters, podcasts

Joyce F. Benenson, Henry Markovits, Caitlin Fitzgerald, Diana Geoffroy, Julianne Flemming, Sonya M. Kahlenberg and Richard W. Wrangham, ‘Males' Greater Tolerance of Same-Sex Peers,’ Psychological Science 2009 20: 184-190.

Roberta L. Coles, ‘Single-Father Families: A Review of the Literature,’ Journal of Family Theory & Review, Vol 7, No. 2 (June 2015), 144-166.

Orjan Falk, Marta Wallinius, Sebastian Lundstrom, Thomas Frisell, Henrik Anckarsater, Nora Kerekes, ‘The 1% of the population accountable for 63% of all violent crime convictions’,

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2014, 49:559–571.

Jo Freeman, ‘Trashing: The Dark Side of Sisterhood,’ Ms magazine, April 1976, pp. 49-51, 92-98.

David C Geary, Jennifer Byrd-Craven, Mary K Hoard, Jacob Vigil, Chattavee Numtee, ‘Evolution and development of boys’ social behavior,’ Developmental Review, Volume 23, Issue 4, 2003, 444-470.

Ryan Grim, ‘The Elephant in the Zoom,’ The Intercept, June 14 2022.

Patricia Draper, and Henry Harpending, ‘Father Absence and Reproductive Strategy: An Evolutionary Perspective,’ Journal Of Anthropological Research, Volume 38, Number 3, Fall 1982, 255-273.

Jeanne M. Hilton, Stephan Desrochers, and Esther L. Devall, ‘Comparison of Role Demands, Relationships, and Child Functioning in Single-Mother, Single-Father, and Intact Families,’ Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 2001, 35: 1, 29—56.

Tim Kaiser, Marco Del Giudice, Tom Booth, ‘Global sex differences in personality: Replication with an open online dataset,’ Journal of Personality, 2020, 88, 415–429.

Hillard Kaplan, Kim Hill, A. Magdalena Hurtado, and Jane Lancaster, ‘The embodied capital theory of human evolution,’ in Peter T. Ellison (ed.) Reproductive ecology and human evolution, De Gruyter, 2001, 293-317.

Arnold King, ‘On Feminism,’ In My Tribe Substack, Nov. 26, 2022.

Sara McLanahan, Laura Tach, and Daniel Schneider, ‘The Causal Effects of Father Absence,’ Annual Review of Sociology, 2013 July; 39: 399–427.

Jessica K. Padgett and Paul F. Tremblay, ‘Gender Differences in Aggression,’ in The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (eds. B.J. Carducci, C.S. Nave, A. Fabio, D.H. Saklofske and C. Stough), October 2020, 173-177.

David Popenoe, ‘Life without Father,’ Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the NCFR Fatherhood and Motherhood in a Diverse and Changing World, 59th, Arlington, VA, November 7-10, 1997.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED416035.pdf

Tania Reynolds , Roy F. Baumeister, Jon K. Maner, ‘Competitive reputation manipulation: Women strategically transmit social information about romantic rivals’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2018, 195-209.

Peter J. Richerson, and Robert Boyd, ‘The evolution of human ultra-sociality,’ in Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt and Frank K. Salter (eds.), Indoctrinability, ideology, and warfare: Evolutionary perspectives, Berghahn, 1998, 71-95.

Marten Scheffer, Ingrid van de Leemput, Els Weinans, and Johan Bollen, ‘The rise and fall of rationality in language,’ PNAS, 2021, Vol. 118, No. 51, e2107848118.

David P. Schmitt, Martin Voracek, Anu Realo, Ju¨ri Allik, ‘Why Can’t a Man Be More Like a Woman? Sex Differences in Big Five Personality Traits Across 55 Cultures,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2008, Vol. 94, No. 1, 168–182.

Aaron Sell, Manuel Eisner, Denis Ribeaud, ‘Bargaining power and adolescent aggression: the role of fighting ability, coalitional strength, and mate value,’ Evolution and Human Behavior, Volume 37, Issue 2, 2016, 105-116.

Manvir Singh, Richard Wrangham & Luke Glowacki, ‘Self-Interest and the Design of Rules,’ Human Nature, 2017 Dec;28(4):457-480.

Josh Slocum, Disaffected Podcast.

Betsey Stevenson, Justin Wolfers, ‘The Paradox Of Declining Female Happiness,’ NBER Working Paper 14969, May 2009.

John Tooby and Leda Cosmides, ‘The Psychological Foundations of Culture,’ in The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture, Barkow, L. Cosmides, J. Tooby (eds), Oxford University Press, 1992, 19-136.

Robert Trivers, ‘Parental investment and sexual selection,’ in B. Campbell, Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, Aldine de Gruyter, 1972, 136–179.

Very few would argue that the foundation of an effective military is highly functioning teams and systems nested within a prestige hierarchy. The ignoramuses in charge simply deny biological reality. To them, the feminisation of the military won't necessarily result in teams being supplanted by cliques and a shift in focus from prestige to propriety. From my limited perspective it has already happened to a significant extent. I just hope we don't have to learn the hard way how effective this transition will be in large scale combat operations.

"Hence, their males have evolved large testes so as to spurt aside the sperm of the previous male to mate with a female and have enough to not be all spurted aside by the next male to do so. We do not have that adaptation." Thank God we don't, just imagine the washing!

In all seriousness, what a wonderfully absorbing and interesting essay. Some points e.g. the differences between male and female bonding, were familiar to me, others hadn't occurred to me before. I hadn't really thought about female features expressing emotion more easily, but it explains why to me, my husband always seems to have either a vaguely angry or a bewildered expression. I had assumed that was simply the natural result of being married to me, but perhaps sex differences have more to do with it.