Great analysis, dreadful framing

A Review of ‘We Have Never Been Woke’

Housekeeping: Lorenzo and I will be hosting a paid subscribers only Chatham House rules chat on Tuesday 30th December (morning in the UK, evening in Australia). Among other things, we’ll be discussing this piece and—given both of us are Australian, at least in part—the Bondi Beach Massacre.

As background for the chat, I recommend reading my piece on Bondi for Law & Liberty, the magazine where I’m senior writer. As you’d expect from a legally-oriented outlet, I have covered some legislative background with respect to Australian immigration and its gun laws.

I did not discuss the ongoing royal commission political football—or the controls on protests the NSW state government has enacted—partly because there was a fair bit of “fog of news” getting around when I was writing (as you will see when you read it, I nearly tripped and fell down the “but Sajid Akram came from Pakistan!” hole).

Lorenzo and I will discuss the unaddressed issues for our paid subscribers; you will get a dedicated Zoom link with a complete set of instructions as usual.

One of the great puzzles of our time is how oppressor/oppressed dichotomies, and celebrations of marginalisation—ideas that came out of Critical Theory, so from meditations on Marxism—came to spread across Western institutions and throughout public discourse. There are a range of factors that matter: the dramatic expansion in universities; the massive expansion in bureaucratisation, whether government, corporate or non-profit; the feminisation of institutions and occupations.

In We Have Never Been Woke, sociologist Musa al-Gharbi provides a key part of the explanation for the spread of such ideas. They were re-packaged as elite signals, as signals of moral righteousness, of how you showed yourself to be a good and worthy person.

Social signals

These new signals of righteousness fitted in with the ideas of equality—particularly of group equality—that arose in the wake of the 1960s equal rights movements. Equality-as-equal-group-outcomes were given extra legal force by the disparate impact ruling of the US Supreme Court in Griggs v Duke Power (1971) and by waves of anti-discrimination legislation.

Consider DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion): it became a way of signalling we really care about merit; we will look for talent anywhere and everywhere (p.260). This was not remotely the only thing going on with DEI, but it was central to how quickly it managed to spread. Righteous embrace of talent had also been a factor in the original DEI programs: the Soviet Korenizatsiya program; Mao’s so-called Black and Red identities; North Korea’s Songbun system.

In the case of DEI, there is a difference between signal and action. Indeed, that difference is central to We Have Never Been Woke, and especially its title. That these moral signals did not get in the way of people acting in their own interests—indeed, they helped them to do so—was precisely the point and the appeal.

The adoption of such being moral signalling generated a commitment to curate information flows so as to protect such moralised cognitive assets; the beliefs and claims about the world that make for truly moral people. This has come to generate very considerable social costs: costs to the health of public discourse; costs to Western elite willingness to confront any moral-signal-inconvenient facts; costs to the quality of schooling and education; costs to social solidarity by the moralised denigration—amounting to exclusion—of voices that failed to play such games.

While We Have Never Been Woke is mostly concerned about social dynamics, Musa al-Gharbi is very much concerned with who is and is not favoured within such dynamics. It is clear that exclusions fell disproportionately on working-class voices who failed to keep up with the latest linguistic taboos.

Those linguistic taboos shift regularly so as to preserve their elite signalling capacity—Latinx anyone? Relatedly, it is hard to understand the sheer, vicious antipathy of so much of the British elite to the visibly working-class Tommy Robinson without understanding the threat he imposed to elite understandings of what made one—what signalled that one was—a moral person.

Those wider social costs for public discourse, institutional health and social solidarity did not fall on those playing evolving elite status games. On the contrary, the cost of undermining—by dissenting from—the shared status game was much more potentially serious. It is only moral to affirm X if it is immoral to affirm not-X.

It became morally respectable—even required—to shun and shame people over their politics. To do so not only showed how moral you were, it showed your commitment to the shared status game of moral-because-believe-correctly. A game that advantages the shrill over the competent.

The historian A. J. P. Taylor once noted that while working class people in Britain did not have to join the Labour Party to affirm their working class status, middle-class intellectuals could do so in no other way. The educated class (“post-material”) takeover of centre-left politics has become so complete that mechanisms to exclude working-class voices now increasingly dominate such politics.

More and more, working-class voters have noticed, and either stopped voting or shifted to voting for populists. The more one experiences elite contempt and exclusion, the more appeal ostentatiously anti-elite politics have.

The synergy of the offered being moral signal with elite networking led to enthusiastic adoption of the offered moral-signalling game. This adoption was beneficial to the adoptees, but that does not mean it was insincere. Our conscious cognition is only a small fraction of our cognition and we Homo sapiens are easily capable of whatever level of self-deception is required to adopt beliefs that work for us.

This is especially so as we are such highly imitative—even mimetic—species as well as a very status-conscious species. This is a moralised status strategy that could—and did—extend to all realms of life: into comedy, advertising, workplaces, schools, universities, professional associations, media, journals, sport, fiction, entertainment, games, hobbies … .

It all works so much better as an elite-signalling game if folk adopt the beliefs required to prosecute it. This then maximises the incentive to curate one’s information flows to protect such moralised cognitive assets. Maximising the personal benefit maximises the social cost of the status strategy.

The advantage of sincerity, even of self-deceiving sincerity, does not mean, however, that there will not be some preference falsification—pretending to believe what one does not. On the contrary, the more social sanctions are used to enforce the shared moralised status game, the more extensive preference falsification is likely to be.

Tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel discusses precisely such preference falsification happening in the Tech sector. The recent “vibe shift” is at least some of those falsifications collapsing in a preference cascade.

Why these ideas?

It was not accidental that meditations on Marxism were sources for these new elite signals of righteousness. The problem with OG Marxism was that it was tough sell to Western elites—we will shoot you, possibly your entire family, and take your property. Not an ideal marketing strategy. On the contrary, Western elites were all too willing to put considerable efforts into opposing Communism—both Communist Parties inside the West and Communist Powers outside the West. That was very much the dynamic of the Cold War era that ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

In stark contrast to we will shoot you, possibly your entire family, and take your property, the new, Critical Theory derived, package said: affirm these beliefs, using this language, and you will signal to the world how moral you are, how much you care. In other words, being truly moral is about displaying-through-affirmation the splendours in your head.

In addition to any other assets folk may have, they could add highly moralised cognitive assets. Even better, these new moralised (cognitive) assets could be used in synergy with their existing advantages. In particular, they actively assisted the networking that is at the heart of elite credentialing and signalling.

Re-packaging those moral splendours in ostentatiously progressive heads so that they could operate as elite-signalling devices turned out to be a massive winner in spreading such ideas and having them colonise Western institutions. Offering members of Western elites moralised cognitive assets proved to just the ticket.

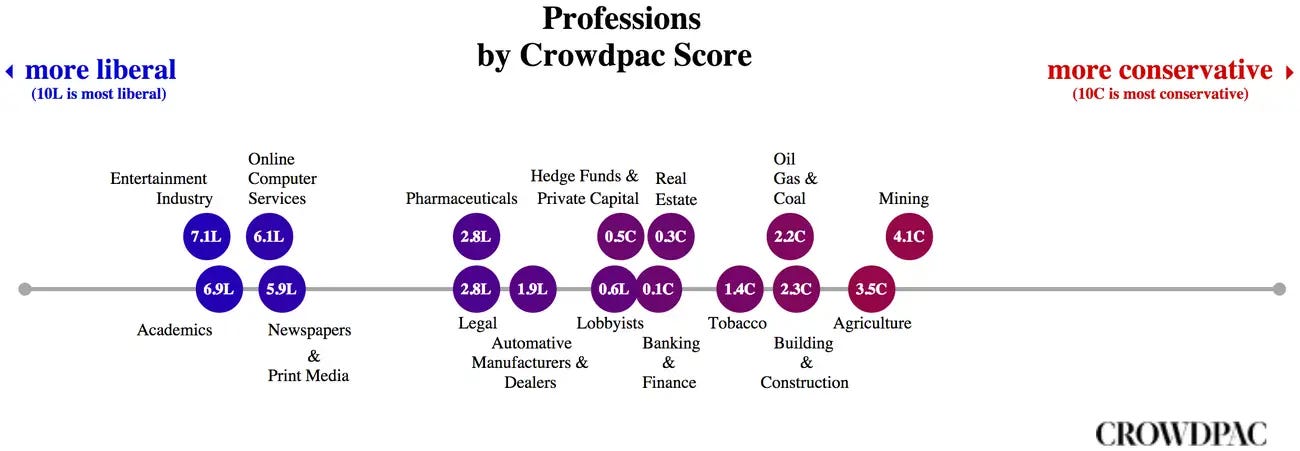

How so? Well, to whom was this re-packaged, piety-display version of ostentatious virtue absolute catnip? To those whose position in society was already based on what was in their heads—yet did not have to face the reality-tests of wresting value from physical things—and to whom a parade of altruism was already a preferred basis to claim position, status and authority.

These are the group that Musa al-Gharbi labels symbolic capitalists. Symbolic capitalists are people whose economic position is defined by their possession of symbolic capital. Musa al-Gharbi is using a sociological definition of capital:

… someone who possesses financial resources (capital) that are used to acquire, exert control over, and extract profits from the means of (material production). (P.7)

This is a terrible definition and concept of capital. That it is central to much sociology is enough on its own to consign the discipline to the dustbin of history. It riffs off Marx’s dreadfully bad concept of capital and reflects Sociology falling into what Arnold Kling nicely calls the tarpit of Marxism. The great advantage of Marxism and its derivatives is that it offers the denizens of such Theory moralised cognitive assets.

Hence, the Communist antecedents for DEI are not accidental. Just as Critical Theory was a way of laundering Marxism so as to insulate the core ideas from the mass murders, tyrannies, and economic stagnation of actual Marxism (i.e. Communism), so ideas derived from Critical Theory proved to be an excellent way of laundering social advantages into self-righteous moral authority.

There is a wider geopolitical irony here. Geopolitically, Communism was the best thing that happened for the United States as it demographically and economically crippled the two states most able to rival it—Russia and China.

Just as the Chinese Communist Party has come to use commerce to break out of the economic stagnation inherent in command economies, status games flowing from derivatives of Marxism have been doing systematic institutional damage to the United States, robbing it of much of what had been its institutional advantages. This pattern is even more advanced in Canada, the UK, the EU. The adoption of toxic status strategies by elites is a great way to bring down a state, a society, a civilisation.

Elite signalling of moral virtue was much less of a change in the Marxian source ideas than it might appear, as left-progressivism has always been based on extolling the splendours in the heads of believers. Even in The Communist Manifesto, a clear distinction is drawn between the proletarians to be liberated and the Communists who will lead that liberation.

There is always a gulf between folk to be equalised and those doing the equalising. The most ostentatious exponents of “equality”—in whatever form, including elimination of distinct classes—are often quite vicious in asserting their moral superiority over all those not so righteously committed. This is a very conspicuous feature of Marx’s own writings, for example.

Connections before transactions

The irony is that the leaden legacy of Marx is most obvious in We Have Never Been Woke precisely in the concept of capital invoked. Economists have a fairly straightforward notion of capital—the economically produced factor of production. This contrasts with the other factors of production—land and labour. So, you can have physical capital (tools, machines, buildings, etc) and human capital (skills and knowledge). It is a fairly short step to social capital (connections and framings that help with risk management; opportunity spotting; collective action problems).

Production requires coordination of factors of production. It also requires effective information flows—plus risk management—with which connections can provide and/or assist. Ronald Coase’s famous transaction costs theory of the firm is precisely about whether to rely on transactions or on connections to manage production and commerce.

We grow up embedded in connections long before transactions become important to us. Even after they do, connections still matter; hence friends, relatives, acquaintances is persistently the most important labour market intermediary.

A large reason why conventional economic analysis of immigration is so hopeless—and a prime example of social science making Western societies stupider—is precisely because societies are treated as connectionless arenas for free-floating transactions where efficiency is the pervasively trumping concern and there are no issues of social resilience.

This analytical failure is aided by a favourable view of immigration itself having become a powerful elite moral signal. Indeed, it is clear that many regard immigrants as “purifying”—indeed decolonising—Western societies.

Hence, there really is no public debate on immigration. There are people in different informational universes shouting past each other, with economists’ commitment to the Theory which is the basis of their social-institutional standing aiding in their curating of the information they receive/take cognisance of. Those different informational universes are themselves largely generated and maintained by curation of information to protect moralised cognitive assets. This is very much part of the social cost of the elite status strategy analysed so usefully in We Have Never Been Woke.

Back to capital

Financial capital may seem a bit of a stretch for the concept of capital. It is less so once one realises that risk management is a fundamental element in economic production. Commerce is very concerned with risk management.

So, what capital does in its various forms is perform an economic function. It is not some mysterious claim on resources. The profound analytical failure of the Sociological concept of capital springs from Marx’s greatly overblown Conflict Theory of social dynamics, famously expressed in his and Engel’s statements that:

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

That:

… every form of society has been based, as we have already seen, on the antagonism of oppressing and oppressed classes.

This generates a concomitant underrating—by those who fall into the tarpit of Marxism—of the cooperative mechanisms that enable human societies to scale up so dramatically.

This replacement of attention to coordination and functionality with an analysis of “clear to us clever folk” exploitation plays much better to academic status games. Conservative concern for making things work is much less appealing in any academic status game than such lofty moralised knowingness.

This is especially as academics do not have to make anything—even their disciplines—work except as an academic status game. The notion that they may have some obligation to serve the society, culture and citizens that pay for, and protect them, is, again and again, not acceptable to academic arrogance. All this is both a reflection, and cause, of the exclusion of conservative voices from so much of academe.

Marx’s dreadful concept of capital leads to capitalist, which is a dreadful term for folk who coordinate land, labour and capital, who engage in risk management and commercial discovery. Many people in business use little or none of their own capital, however much they may be coordinating capital with land and labour.

The deeply misleading concept of capitalist—and for that matter of capitalism—has spread well beyond Marxism and leads to silly “crank the handle/just add factors of production” conceptions of economic growth and “just add capital” failures of foreign aid. It also obscures why different cultural groups can have dramatically different economic outcomes—due to having very different propensities to network productively; to coordinate; to risk manage; to discover; to generate and use capital.

The dreadful Marxian/Sociological concept of capital feeds directly into “success = oppression” and to viewing differences in social outcomes between groups as presumptive moral failures. The latter is something that Musa al-Gharbi’s commentary in We Have Never Been Woke buys into, without getting in the way of his underlying analysis—though it does help him highlight the gulf between signal and action.

After invoking the Sociological concept of capital, Musa al-Gharbi continues:

Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu, we can define a symbolic capitalist as someone who possesses a high level of symbolic capital and exerts control over, and extracts profits from, the means of symbolic (re)production. (P.7)

That so many of these people are employees—and even fewer of them employ anyone themselves—makes the notion of them as capitalists even more misleading. Yes, the ones that do employ people are typically doing so to help them commercialise their skills but that commercialisation is not what they have in common.

The Introduction goes through Musa al-Gharbi’s personal history and what led him to where he is. He starts the first chapter—On Wokeness—with a short biography of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002) before moving on to Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic capital.

… the resources available to someone on the basis of honor, prestige, celebrity, consecration, and recognition. (P.24)

Moreover,

These symbolic aspects of social life are intimately bound up with power and wealth, or with material and political needs and aspirations. According to Bourdieu, the roles people are assigned to on the basis of their symbolic capital (or lack thereof) may actually be more important than more conventional economic factors in determining how power is arranged in society. And regardless of how such inequalities come about, it is primarily through symbolic capital that they are legitimised and maintained. (Pp24-25)

Given the Queer Theory nonsense of “sex assigned at birth”, we should be particularly alert to the analytical red flag in “roles people are assigned to on the basis of the symbolic capital (or lack thereof)”. The phrasing of “how power is arranged in society” is also a bit of a worry.

Why would we call any of this capital? What about issues of expectations, conflicting presumptions, contested claims, performance? If status and authority claims are such important issues, is the use of such ersatz economic terms really the way to go in analysing it? Yes, the ability to garner people’s attention is absolutely a crucial element in status but that is something that itself requires management precisely because it is so interactive. Why do we have culture anyway? What does it do and how?

No, folk do notice

Musa al-Gharbi continues:

However, symbolic capital operates much more subtly than other forms of power and wealth. Indeed, when deployed effectively, neither the person wielding this capital nor the people it is exercised on will consciously recognize the power dynamics at play. Instead, interactions, relationships and states of affairs will seem natural, necessary, inevitable, or in any case normal to all those involved. (P.25)

“Effectively” is doing a lot of work here. Many folk are patently alienated by the authority claims being advanced by so-called “symbolic capitalists”, and that fact that social sanctions are so much part of the status-signalling package means they require enforcement, precisely because they are not “just accepted”.

By contrast, legal academic Joan Williams back in 2016 picked up on class-based cultural tensions because the claimed authority of the “symbolic capitalists” is not only not invisible to working-class people, it is openly resented:

For months, the only thing that’s surprised me about Donald Trump is my friends’ astonishment at his success. What’s driving it is the class culture gap.

One little-known element of that gap is that the white working class (WWC) resents professionals but admires the rich. Class migrants (white-collar professionals born to blue-collar families) report that “professional people were generally suspect” and that managers are college kids “who don’t know shit about how to do anything but are full of ideas about how I have to do my job,” said Alfred Lubrano in Limbo. Barbara Ehrenreich recalled in 1990 that her blue-collar dad “could not say the word doctor without the virtual prefix quack. Lawyers were shysters…and professors were without exception phonies.” Annette Lareau found tremendous resentment against teachers, who were perceived as condescending and unhelpful.

Michèle Lamont, in The Dignity of Working Men, also found resentment of professionals — but not of the rich. “[I] can’t knock anyone for succeeding,” a laborer told her. “There’s a lot of people out there who are wealthy and I’m sure they worked darned hard for every cent they have,” chimed in a receiving clerk. Why the difference? For one thing, most blue-collar workers have little direct contact with the rich outside of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. But professionals order them around every day. The dream is not to become upper-middle-class, with its different food, family, and friendship patterns; the dream is to live in your own class milieu, where you feel comfortable — just with more money. “The main thing is to be independent and give your own orders and not have to take them from anybody else,” a machine operator told Lamont. Owning one’s own business — that’s the goal. That’s another part of Trump’s appeal.

Hillary Clinton, by contrast, epitomizes the dorky arrogance and smugness of the professional elite. The dorkiness: the pantsuits. The arrogance: the email server. The smugness: the basket of deplorables

Musa al-Gharbi continues riffing off Bourdieu:

Even those at the bottom of social hierarchies will often acquiesce or resign themselves to their own domination. As Bourdieu put it, “Symbolic power is the invisible power which can be excised only with the complicity of those who do not want to know that they are subject to it or even that they themselves exercise it.” (P.25)

There is clearly nothing invisible about such authority claims to working-class folk. What may well be invisible is the use of morality for social signalling and social aggression by those doing so: but that is an evolved human mechanism for social aggression which seeks to avoid physical backlash—and to be more effective as social aggression—by piggy-backing off status-through-propriety; i.e. status through ostentatious norm adherence.

Moralised social aggression that does not know when to stop is a curse of our time, one greatly enabled by social media. Much of the contemporary mobilisation of such aggression was pioneered by activists on behalf of Jews. Musa al-Gharbi himself was targeted in this way, and ended up working in a shoe shop for several years. We need the modern equivalent of the ducking stool to police our social emotions as part of restoring health to our public discourse and institutions.

Fortunately, once Musa al-Gharbi has labelled symbolic capitalists as people possessing symbolic capital, then the concept of capital and being capitalists performs no more analytical work in We Have Never Been Woke. For all the rest of his analysis, he is looking at status, claims to authority, contests over position, the operation of networks.

One of the strengths of the book is pointing out that these claims are a class pattern that can, and do, attack both rightwards and leftwards. They often rely on academic and bureaucratic cowardice. al-Gharbi comes from a military family and is clearly unimpressed by the pervasive cowardice of academics.

The capitalist in symbolic capitalist thus becomes a way of saying elite/having elite pretensions and, perhaps, a labelling jab that accords with a certain cachet of Sociological Seriousness. The last resounds with me not at all, since I regard Sociology as, at best, the Anthropology of developed societies and, at worst, a mess of Theory no one should call their intellectual home.

After all, what is examining in a scholarly way: status; claims to authority; contests over position; the operation of networks? Classic Anthropology. What We Were Never Woke does demonstrate is that perceptive social noticing, backed up by careful empirical work assembling relevant and useful data, can overcome a bad analytical framework—especially one mainly used for labelling (and perhaps signalling).

Only the latest Awokening

In the second chapter—The Great Awokening(s)—Musa al-Gharbi argues that what commentator Matt Yglesias famously labeled The Great Awokening was merely the latest in a series of such Awokenings since the early C20th. The first was in the 1920s, the next in the late 60s, the third in the late 80s and the fourth from the 2010s to present.

The Awokenings represent sharpened contests for position and resources in periods when there is an over-supply of certain types of human capital, relative to demand for that knowledge and skills. Hence, a sharpening of moral claims, of ostentatious altruism, both as a way of more intensely competing for available positions—including, for younger cohorts to push aside older ones—and for expanding the number of positions available on the grounds of both commitment to worthy moral projects and analytical utility.

Both these things have been conspicuous features of the most recent Great Awokening. Discourses that can help with such claims are clearly favoured among such occupations.

Like political scientist Eric Kaufmann, Musa al-Gharbi emphasises the use of various moral discourses over their content. Yet ideas have consequences. It is not accidental which discourses get adopted. To at least some degree, these discourses then have to be acted out.

But, I would agree with Musa al-Gharbi, the acting out is the key thing. That is, however, not quite the killer point about hypocrisy—about the gap between signal and action—it looks like. Left-progressivism has NEVER achieved what it says it’ll do on the tin. Ever. “We Were Never Woke” is up there with “true Communism has never been tried”.

Yes, a discourse adopted as an elite status strategy—that then replicates and advances elite networking—absolutely can have remarkable little impact on the social outcomes it pretends to care about. Gregory Clark’s work on how little social mobility there is across human societies makes that even less of a surprise.

But the notion that we can achieve equal outcomes between social groups is as much an unnatural social fantasy as Communism itself. To set equality—particularly equality understood as equal outcomes between groups—as the supreme moral benchmark is a nonsense. Especially when it involves—as it does again and again—creating a moral caste system of stigmatisation: stigmatisation from which affirming righteous belief can be a protection.

But the very impossibility of achieving such equal outcomes makes it a useful social fantasy. The moral project that is made absolute moral trumps—but can never be achieved—is a claim on authority, power and resources that never goes away. Musa al-Gharbi seems to buy into that particular social fantasy too much to fully grasp how it being unattainable is central to its utility.

The third chapter (Symbolic Domination), the fourth (Postmaterialist Politics), fifth (Totemic Politics), sixth (Mystification of Social Processes) examine the authority claims of the symbolic capitalists, their politics, their self-deceptions and how their patterns extend beyond even the most currently dominant set of social signals.

Needed: new status games

What We Were Never Woke does clarify to the thoughtful reader, is that to fully stop “wokery”—including repackaged versions—we have to find a new elite signalling and status strategy. To be an improvement, not merely a replacement, it will need to be a pro-social elite signalling and status strategy. One that is far more conducive to open discourse, facts, science, and social solidarity than the current “woke” version, which is none of those things.

Alas, it will be hard to compete with a status strategy that is both so self-deceptively self-serving and so morally and intellectually lazy. I’m pretty sure it will continue to have life even if “woke” goes off the boil. Somehow, as a friend has noted, we have to “Make Doing Hard Things Sexy Again”. It is hard to see how we will manage that without profoundly reforming, even gutting, higher education.

There are many fine things about Musa al-Gharbi’s We Have Never Been Woke. The book is clearly written, in a matter-of-fact style. It is full of useful empiricism, of effective and appropriate use of evidence. It has a solid historical sense. The author has the gift of noticing.

It is sad about the theoretical framework. Riffing off Bourdieu’s cultural capital suffers from way too much capital, not nearly enough culture; not nearly enough simply concentrating on the social dynamics of status, networking, authority claims and how they get contested. But the central point—that these are a series of moralised authority claims being made by a class under pressure through over-supply—is powerfully conveyed.

References

David Cayley (ed.), The Ideas Of Rene Girard: An Anthropology of Violence and Religion, David Cayley, 2019.

Gregory Clark, The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility, Princeton University Press, 2014.

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018.

Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´inez-Toledana, Thomas Piketty, ‘Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages In 21 Western Democracies, 1948–2020,’ The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol. 137, 2022, Issue 1, 1-48. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/137/1/1/6383014

Musa al-Gharbi, We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite,

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Mark Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233. https://www.csc2.ncsu.edu/faculty/mpsingh/local/Social/f15/wrap/readings/Granovetter-revisited.pdf

Oliver Heath, ‘Policy Alienation, Social Alienation and Working-Class Abstention in Britain, 1964–2010,’ British Journal of Political Science, 48(4), (2016), 1053–1073. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/70E409B4E2274FAE7844449B95DA0EBB/S0007123416000272a.pdf/div-class-title-policy-alienation-social-alienation-and-working-class-abstention-in-britain-1964-2010-div.pdf

Frank H. Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Cosimo, [1921] 2005.

Timur Kuran, Private Truths, Public Lives: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification, Harvard University Press, [1995] 1997.

Girijasankar Mallik, ‘Foreign Aid and Economic Growth: A Cointegration Analysis of the Six Poorest African Countries,’ Economic Analysis and Policy, Volume 38, Issue 2, 2008, 251-260. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/99051097/v38_i2_07_mallik-libre.pdf

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

Stanislav Andreski's 50 yo classic 'Social Sciences as Sorcery' is not in print anymore as far as i know. So copies are rather expensive. Below a free pdf version:

https://gwern.net/doc/statistics/bias/1973-andreski-socialsciencesassorcery.pdf

"a very status-conscious species"

The taproot of my misanthropy - those who succumb to such trivial stupidity deserve to be treated as something approaching livestock. Or I'm simply a defective human.