Social justice as social leverage

Is social justice advancing our evolution or gaming it?

This is the first in a series of essays dissecting the social mechanisms that have led to the strange and disorienting times in which we live. Helen commissioned them from Lorenzo from Oz when it became clear that her substack was going to be much more popular than expected.

The publication schedule is available here, and will remain pinned at the top of Helen’s substack throughout the publication process. Helen will also link each essay there as it’s published.

Lorenzo is on Twitter @LorenzoFrom. Helen’s on the Bird Site @_HelenDale

Both of us will tweet each essay as it’s published. Do subscribe below so that you don’t miss anything, and help spread the word.

Note: at the end of each essay, you’ll find a detailed bibliography and suggestions for further reading.

Meet the Humans

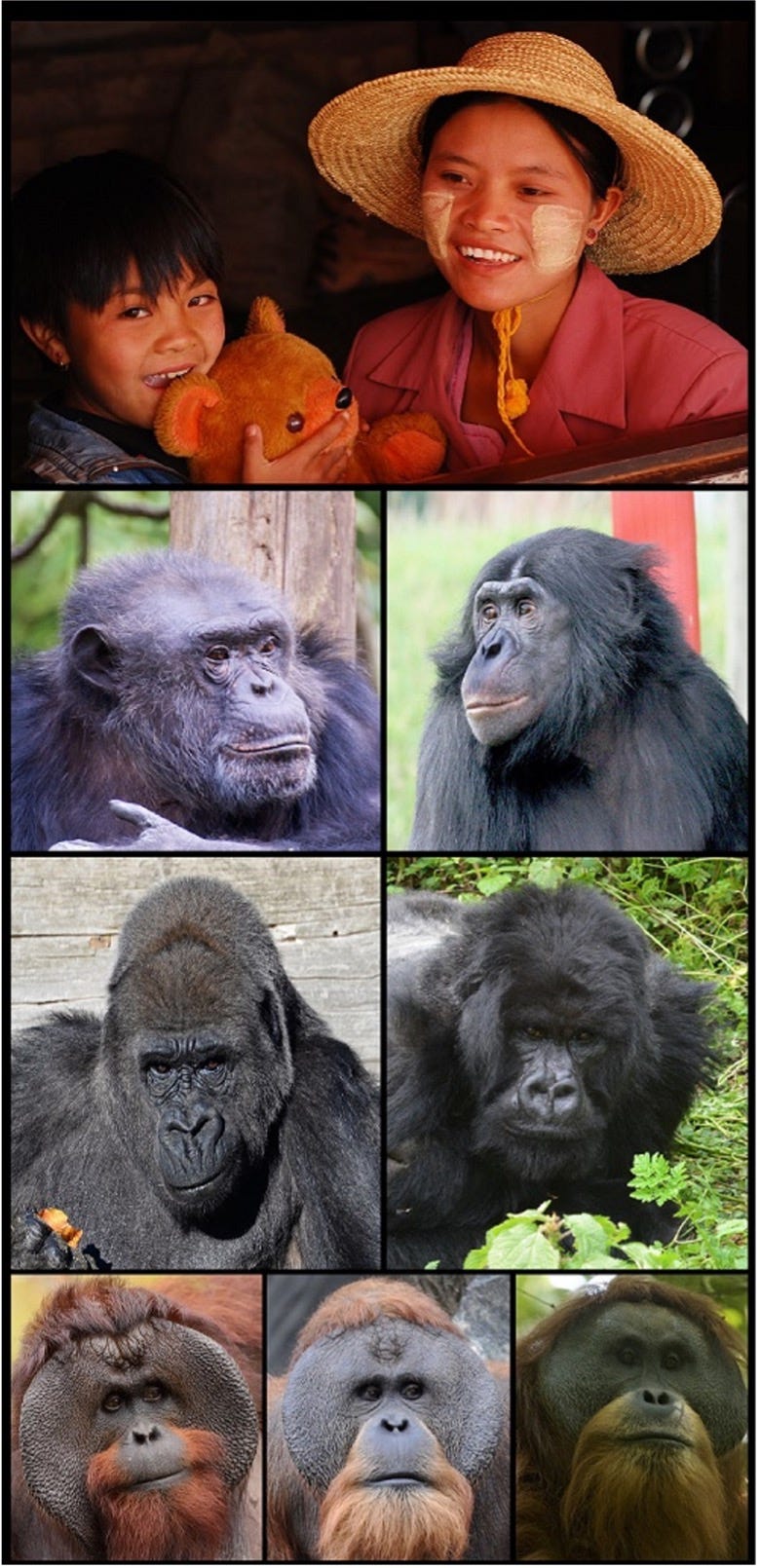

Homo sapiens are the most cooperative of primates.

We evolved cooperative subsistence strategies because we became predators without rending claws or killing jaws. We became apex predators through tools and cooperation.

We started down this path before we became human. Our Australopithecine ancestors used stones to smash open bones to extract their marrow and skulls to scoop out the brains. Bones and skulls leftover from the kills of African predators. (Pause for image of our Australopithecine ancestors staggering across the savannah in search of “brains! brains!”.) We moved on to doing our own kills and cooking them around shared fires.

Our Neanderthal cousins (who are also, to a small extent, our ancestors) were as carnivorous as wolves, hyenas and lions while also, like all humans, being highly adaptable in their dietary strategies. Neanderthal carnivory may be somewhat over-stated by the level of stable isotopes in their collagen, as they also ate carnivores. Still, cooperative tool-making and use was crucial to their subsistence strategy, as it was for all human ancestors.

We humans also evolved cooperative reproduction strategies. It takes almost 20 years for a human forager child to attain the skills to forage as many calories as it consumes.

It became evolutionarily advantageous for a mother to survive for around 15-20 years after the birth of her last surviving child, creating lengthy post-menopausal survival. Such survival allowed her to invest effort in her children’s children.

The evolutionary pressure to produce bipedal pelvises structured for energy-efficient, long-distance running to run down prey to exhaustion interacted with the evolutionary pressure for larger brains, creating unusually risky childbirth and unusually helpless infants. We evolved so that much of our brain growth was postponed until after birth. Brain size was not confined to what could pass through a bipedal pelvis.

Human babies spend about 40 per cent of their calories feeding their growing brains. They are helpless brain casings with attached feeding and elimination mechanisms.

Long childhoods meant that birthing another child could not be delayed until the previous child was a juvenile, as other primates do. Otherwise, the gap between children would be far too long for a viable reproduction strategy. A human mother came to care for children of different ages at the same time.

Such vulnerable late pregnancies, helpless infants, long childhoods and “stacked” children meant that risks had to be transferred away from child-rearing. Successful human child-raising became a cooperative, risk-transferring, strategy. Something that not only all human societies do, but is, in all cases, one of their fundamental features.

Killing to cooperate

We humans likely murdered our way to further cooperation: subsistence and reproduction was greatly aided by selective homicide.

We Homo sapiens, along with our Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees) cousins, are the most proactively aggressive primates. The primates most likely to engage in premeditated violence, including homicide, against members of our own species.

We Homo sapiens are also the least reactively aggressive of primates. We are far less likely than any other primates to respond with violence to the actions of other members of our species.

This combination of being highly proactively aggressive, yet not very reactively aggressive, makes us unusually deadly when we cooperate. It also makes us fantastically socially capable, as we have proved able to develop so many ways, so many mechanisms, to cooperate.

How did we achieve this unusual combination of features? The best hypothesis is by selective murder. Human beta males got together and systematically killed off the alpha males.

As different brain circuits are involved, proactive aggression was used to select murderously against reactive aggression. Alpha male dominance is very much about being willing to react with violence.

Such a process of killing off the alpha males has both archaeological evidence (larger males with bashed-in skulls) and anthropological evidence. Forager societies systematically repress dominance behaviour: by derision, by gossip, by shunning. If need be, by killing.

Dominance, top-down status, is the normal form of status in group-living mammals, including our primate cousins. Systematic selection against dominance by killing off alpha males led to the evolution of two other forms of status among us Homo sapiens. One is prestige: status through competence; through demonstrated capacity; through successful risk-taking. Young human males in particular are prone to seek such status.

The other is propriety: status through following and exemplifying norms. A cooperative, group-living species needs to be able to both encourage, and sort, competence and to have attention paid to group cohesion. Women have tended to be particularly concerned with propriety, for stronger group cohesion generally better protects them and their children.

Prestige and propriety became the social currencies of human cooperation. Especially as our cooperative subsistence and reproduction strategies led us to becoming the most normative of species.

Becoming normative

Expectations are if-then predictions. As there is no information from the future (information is caused, and causation runs forward in time, not backward) we rely on expectations to act.

The more we have shared expectations, including about each other, the more reliably we can cooperate. So, we evolved ways of generating robustly congruent expectations about each other.

Norms are if-then rules. A shared set of if-then rules followed within a group makes it easier to act according to a common set of if-then predictions. The more robust the shared norms, the more reliably we can cooperate.

By developing a normative capacity that levers off our emotional architecture, so gives norms emotional oomph, means robustly congruent mutual expectations could be generated. The sort of robustly-followed norms that lead to, for instance, systematic suppression of dominance behaviour among forager peoples.

Another way to make commitment to norms more robust is to embed them in a religious framework. Something with divine (so elevated) authority that creates a sense of the sacred (so that which cannot be traded-off).

By heightening authority and narrowing and channelling the acceptable, engaging in common rituals and markings or ways of dressing that reinforce the sense of common commitment, the religious can become more reliable coordinators among themselves. This gives them a selection advantage which likely accounts for how pervasive religion is among human societies.

Our normative capacity makes us able to cooperate to such an extent that we can create enormously complex societies. It also creates a potential source of evolutionary advantage within our social groups: by “gaming” other people’s expectations, including expectations based on norms, to our own advantage.

That our normative capacity levers off our emotional architecture means that being emotionally disordered can lead — to use an old expression—to moral insanity. Highly manipulative personalities can seek to use norms that others expect folk to be committed to, but are not, to their own advantage.

This is why so many societies evolved various character tests to select against such personalities and such behaviours.

What has also been selected for are certain types of self-deception: using ostentatious commitment to norms to our own advantage. Including as a cover for aggression against others. Particularly relational aggression: attacking and undermining a target person’s connections with others.

The advantage of being self-deceptive in these ways is that if we are convinced what we are doing is righteous, the cognitive load on us is much lower and our persuasiveness (and so the effectiveness of our relational aggression) is likely to be much higher.

Across history, human societies waver back and forth between strong mechanisms of social cohesion (particularly if a group sees itself as facing a common threat) and socially-corrosive mechanisms of self-interested (albeit often significantly self-deceptive) gaming of norms, and of other social-connection mechanisms.

An early, and highly perceptive, analysis of shifts between strong group-cohesion and corrosive self-interest was provided by the first, and arguably greatest, historical sociologist, Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), in his analysis of the waxing and waning of assabiya (group feeling).

Moralised, coordinated, self-interest?

We live in a time when social justice is much invoked. The question becomes: how much is this, as it purports to be, concern for creating a better society, and how much is moralised (even self-deceptive) self-interest?

How much is it instantiating norms and how much is it gaming them? If it is gaming them, how much—and what forms of—self-deception are involved?

How much is it a status strategy? If it is a status strategy, what sort of status strategy?

While forager societies do systematically suppress dominance, dominance has not disappeared from human societies. There are still primaeval “do as I say or I will thump you” dominance games played, as well as dominance games via emotional intimidation.

Dominance in human societies often has a significant coalitional element to it, where dominance is created and maintained via some team or clique. All sorts of reward-and-punish strategies can be used to create and sustain such dominance.

Propriety also can shade into dominance. Especially if sanctions are to be invoked against those who are seen to act against propriety.

Social justice is concerned with social leverage. With developing the capacity to access and use social resources. But, again, the question is: how much is this social leverage to achieve stated social-betterment goals and how much is this social leverage to advantage those using the social-justice strategy?

These questions make a huge practical difference. If social justice is about achieving better outcomes, then that is something one can bargain over. If social justice is for its proponents (consciously or unconsciously) a status-and-social-leverage strategy, then any concession just feeds the strategy. The strategy will then continue as long as it works.

Fortunately, these questions can be tested. When social justice is about improving the human condition, then certain forms of behaviour will be displayed. When social justice is a status-and-social-leverage strategy for its proponents, different patterns of behaviour will be displayed.

Social justice as social leverage

Again and again, we observe that once something is declared to be a matter of social justice, opposition to such a claim becomes illegitimate. This is not a bargaining-to-make-things-better strategy. This is a social dominance strategy.

Ostentatious moralising can make for an effective social dominance strategy. It gives the strategy rhetorical power that can be used to disarm or intimidate others. It provides a mechanism for coordination as people use approved language, and other social cues, as signalling devices. It provides a morally empowered, and so self-motivating, narrative for proponents.

All of which is much more effective, including because it imposes less of a cognitive load, if its proponents are blind to self-interest. Moralisation can be an excellent status-and-social-leverage mechanism. We have, after all, had thousands of generations of evolution to produce the capacity to game normative claims in our own interest.

To improve the human condition, by contrast, we must have a certain open-minded humility toward evidence. To be willing to go where the evidence goes, so as to be more effective, given how the world (and we) are structured.

Again and again, we do not see this open-minded humility among advocates of social justice. We do not see open-minded, genuinely evidence-based, attention to social dynamics, to how things work. On the contrary, we see stigmatising of those who raise awkward facts or complications.

The less social justice is tied to serious analysis of social dynamics, and likely social outcomes, the more it is primarily being used a status-and-social-leverage strategy. This is even more true when social analysis itself is driven by declared social justice implications.

If social justice was concerned for what it purports to be concerned with—creating a better society—it would seek to be broadly persuasive and concerned with what less socially advantaged folk are concerned about, and what they have to say. Again and again, social justice does the opposite of this. Instead, it acts as status-and-social-leverage strategy, as a dominance strategy, seeking to determine who may speak and what it is acceptable to say.

Demanding a blank slate

All claims derived from the doctrine that humans are cognitive blank slates are false. To have the cognitive capacities we do, it is literally impossible for us to be blank slates. Our cognition has to be significantly structured to learn in functional ways.

Reinventing cognitive adaptations every generation is not remotely a way for reproductive survival and success. Hence our normative capacity leverages off our emotional architecture to generate the robustly congruent expectations from shared norms that provide cooperative advantage.

But social justice as status-and-social-leverage is driven towards blank-slate claims. For the less constrained by underlying structures—such as innate human cognitive traits—the grander the imagined social justice future can be. So the more rhetorically dominant its claims can be. The more motivating its aspirations can be.

Dominating language

The less our evolved structures are accepted as generating constraints, the more elevated is the justifying moral grandeur while a greater quantity of social resources are required to achieve moral grandeur. Social justice can then expand and apply to every aspect of society.

Including language. The more language is held to structure social outcomes, the more language is held to be the vehicle for creating social outcomes, the more language itself has to be controlled to achieve the transformations demanded by social justice. Including by setting what’s acceptable to say and how it’s to be said.

Capital is the produced means of production. Human capital is learnt skills, abilities, knowledge. Cultural capital is human capital specific to the creation and transmission of culture.

Human-and-cultural capital classes include priesthoods, clergy, clerisies, members of vanguard political parties. Controlling legitimacy, setting what is proper and improper, is a classic social leverage mechanism possessors of human-and-cultural-capital use.

Prestige opinions and luxury beliefs

A key way the social justice status-and-social-leverage strategy operates in contemporary societies is by in-group signalling. This is based on prestige opinions (opinions that mark one as being of the smart and the good) and luxury beliefs (prestige opinions with entry costs).

Luxury beliefs are beliefs that, if acted upon, have costs for folk of lower socio-economic status that either preclude them accepting them or have disastrous consequences if they do. They are prestige opinions with entry costs. Defund the police is a classic luxury belief.

Such beliefs are assets, providing status, coordination and leverage. And where beliefs are assets, those assets have to be protected.

If believing X makes one of the good and the smart, then believing not-X makes one malicious, stupid, ignorant, and so not a legitimate participant in social discourse. A propensity towards censorship is built into the use of beliefs as markers of status.

Writer Chris Bray nicely characterises this as anti-discourse discourse: language riddled with fearful emotion to close down debate and stigmatise dissent. This is both a social dominance mechanism (driving alternatives out of the legitimate public space) and a status strategy (only those who agree with us are truly moral).

As I’ll explore in later essays, one signals one’s members of the progressive, the social-justice oriented, moral elite by various required affirmations plus not noticing of things awkward to the discourses of in-group legitimacy. One signals even more strongly one’s in-group status by stigmatising those who engage in wrongful noticing of awkward matters.

Fearful anti-discourse discourse signals the limits of the acceptable while reinforcing its own all-trumping moral urgency. Thus do elite media and journalists not only tolerate censorship but are advocates for, and practitioners thereof. Practitioners and purveyors of a discourse of required affirmations and not noticings and denouncers of wrongful noticing.

Hence, far from being concerned with careful analysis of evidence, again and again social justice determines what is acceptable, and what is unacceptable, to cite as evidence. Doing so based on what suits the status-and-social-leverage strategies.

This facilitates polarisation through mutual support while closing off acceptable alternatives. Consider what legal scholar Cass Sunstein says about group polarisation:

The underlying mechanisms have a great deal to do with skewed and limited argument pools, and with people’s desire to maintain relative position of a certain kind (perhaps as a heuristic, perhaps for reputational reasons, perhaps because of self-conception).

We can absolutely see these mechanisms in operation with social justice progressivism. Sunstein also notes the role of rhetorical asymmetries fostering movement in a particular direction.

Focusing on imagined futures sets up rhetorical asymmetries, as the imagined future can be as perfect as one wants, while what exists inevitably has to deal with trade-offs and has a flawed history. The imagined future thus rhetorically trumps the flawed present and the awful past.

By examining its patterns, we can see how much social justice has increasingly evolved into a self-deceptive moralising status and social leverage strategy. A mutually coordinated, networked set of status-and-social-leverage strategies based on shared signals.

A set of outlooks and behaviours that, as we shall see, specifically advantages the human-and-cultural-capital class. There has been social selection for what enables more effective gaming of our normative capacity in the interests of those who sign on for social justice.

By these mechanisms, mutually supporting and coordinating networks are set up. As such networks grow, so does the status advantage of being within the network and the status cost of not being so. These network effects enable holders of prestige opinions and luxury beliefs to dominate organisations and institutions.

Sneering, moralised arrogance is a pattern among contemporary progressives: the maximum amount of self-righteous entitlement coming from the minimum amount of knowledge and intellectual effort.

What has become known as “woke”, but is more precisely described as Post-Enlightenment Progressivism (or even Counter-Enlightenment Progressivism) operates as an ever-evolving status strategy, an ever-evolving mechanism for normative and social dominance.

One of its features is a near-permanent state of moral hysteria, both as a mechanism to de-legitimise criticism of whatever is being proposed and as a motivating self-identity. These are the people Who Fight Great Evil.

Unappeasable

As noted above, because social justice is not outcome-directed (so outcome-limited), you cannot appease people who use the social justice moralised status-and-social-leverage strategies. On the contrary, they will continue to use the strategy until the strategy itself becomes dysfunctional. The more the social justice status-and-social-leverage strategy is fed, the more it continues to be functional. The more it is confirmed as an effective strategy, the more it will be pursued.

Appeasement makes it worse, not better. Feeding the strategy intensifies and spreads the strategy.

Later essays will explore the role of universities in generating these patterns, in the evolution of social justice as self-deceptive status-and-social-leverage strategy. I will address how the decay of the universities has enabled that evolution and been accelerated by it.

One of the key social functions of universities is the provision of signals of competence and capacity. Universities that actively degrade those signals are dysfunctional for society as a whole.

Social justice is above all oriented towards the future. The moral grandeur of social justice is precisely based on how grand the imagined future is.

To illustrate this, I’ll start with the original template for creating a future society of unparalleled moral significance. The original template of the politics of the transformational future.

Hence, in the next essay, I’ll consider the falsities and failures of Marxism and how its failures led to the evolution of new forms of transformational politics.

References

Books

Scott Atran, In Gods We Trust: The Evolutionary Landscape of Religion, Oxford University Press, [2002], 2004.

Joyce F. Benenson with Henry Markovits, Warriors and Worriers: the Survival of the Sexes, Oxford University Press, 2014.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N J Dawood, Princeton University Press, [1377],1967.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

Articles, Papers, Essays, etc.

Christopher Boehm, “Egalitarian Behavior and Reverse Dominance Hierarchy”, Current Anthropology, Vol. 34, No.3. (Jun., 1993), pp. 227-254 (with Comments by Harold B. Barclay; Robert Knox Dentan; Marie-Claude Dupre; Jonathan D. Hill; Susan Kent; Bruce M. Knauft; Keith F. Otterbein; Steve Rayner and Reply by Christopher Boehm).

Judith K. Brown, ‘A Note on the Division of Labor by Sex,’ American Anthropologist, Vol.72, Issue 5, October 1970, 1073-1078.

Luca Fiorenza, Stefano Benazzi, Amanda G. Henry, Domingo C. Salazar-Garcia, Ruth Blasco, Andrea Picin, Stephen Wroe, and Ottmar Kullmer, ‘To Meat or Not to Meat? New Perspectives on Neanderthal Ecology,’ Yearbook Of Physical Anthropology, 156:43–71 (2015).

Zach Goldberg, ‘How the Media Led the Great Racial Awakening,’ Tablet, August 05, 2020.

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/media-great-racial-awakening.

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353.

Rob Henderson, ‘Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class—A Status Update,’ Quillette, 16 Nov 2019.

Hillard Kaplan, Jane Lancaster & Arthur Robson, ‘Embodied Capital and the Evolutionary Economics of the Human Life Span’, in Carey, James R. and Shripad Tuljapurkar (eds.), Life Span: Evolutionary, Ecological, and Demographic Perspectives, Supplement to Population and Development Review, vol. 29, 2003. New York: Population Council, 152-182.

David C. Lahtia, Bret S. Weinstein, ‘The better angels of our nature: group stability and the evolution of moral tension,’ Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 2005, 47–63.

D. Rozado, R. Hughes, J. Halberstadt, ‘Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with Transformer language models,’ PLoS ONE, 2022 17(10): e0276367.

Richard Sosis, ‘The Adaptive Value of Ritual,’ American Scientist, Vol. 92, March-April 2004, 166-172.

Cass R. Sunstein, ‘The Law of Group Polarization,’ John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 91, University of Chicago, 1999.

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136.

John Tooby and Leda Cosmides, ‘The Psychological Foundations of Culture,’ in The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture, Barkow, L. Cosmides, J. Tooby (eds), Oxford University Press, 1992, 19-136.

Jessica C. Thompson, Susana Carvalho, Curtis W. Marean, and Zeresenay Alemseged, ‘Origins of the Human Predatory Pattern: The Transition to Large-Animal Exploitation by Early Hominins,’ Current Anthropology, Volume 60, Number 1, February 2019.

Richard W. Wrangham, ‘Two types of aggression in human evolution,’ PNAS January 9, 2018 vol. 115 no.2 245–253.

Wokeness bears all the hallmarks of fundamentalist religion...which, of course, it is.

The discussion of hominid evolution at the beginning of this is so fascinating.