The Klan Springs Eternal

A Pandemic of Fake Hate

Some people love trials, and I’m not talking about lawyers (or jurors, or police, or bailiffs, or even judges) here. I’m talking witnesses, and, sometimes, accused criminals. That is, there are people for whom a trial is an opportunity — perhaps their only opportunity — to be heard, to command an audience, to feel real and alive.

There are folk who view trials (and legal action more widely) as dramas where they can be a “star”. This can manifest out of court, too. I once saw a particularly histrionic family client throw an office ashtray at another solicitor’s head when he didn’t get the outcome he wanted at trial.

Such people contrive to land in court by any means possible, although the most common involve making false crime reports or bringing frivolous civil claims. My first “baby barrister” memory does not involve a scratchy wig or excessively warm robes (this in country Queensland, remember, which is hot by UK standards even in winter). It’s of the number of people who hang around courthouses and treat trials as spectacles for which they do not have to pay. Murders and rapes are always popular among, ahem, viewers.

Non-lawyers are usually astonished when I say this. Inevitably, I have to explain further. “Wasting police time” and the more serious “perverting the course of justice” have been on the books in various forms for centuries, for example, while vexatious litigants (the civil court equivalent) existed in Ancient Rome. Roman jurists complained about people lingering outside courthouses “looking for opportunistic reasons to bring suit”.

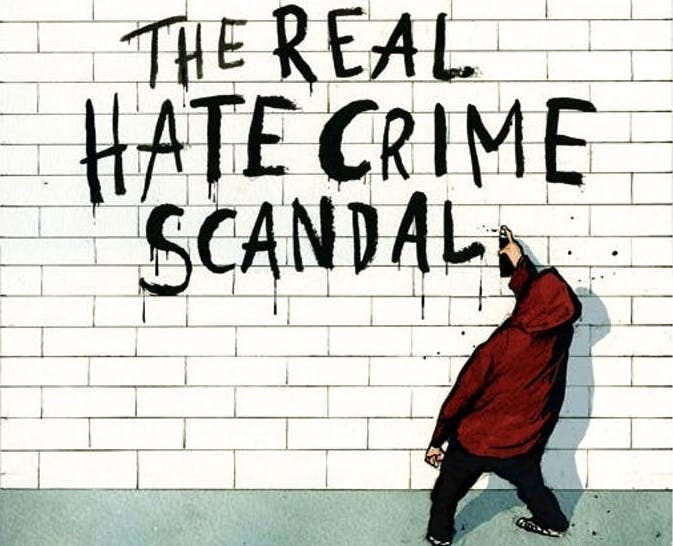

It’s something I’ve been called on to discuss quite a bit of late given there’s been a global uptick in false hate crime reports and false crime reports more broadly. However, while it’s true people do this sort of thing because there’s a psychological payoff, a truism of economics is that you get more of what you subsidise and less of what you tax.

By indulging such mantras as “believe women” or “believe the victim” we’ve succeeded in making a bad thing that’s always existed worse. It now looks like the Klan springs eternal: fake hate has become a perverse way for members of racial minorities to use fictional attacks by members of white hate groups to explain away their own struggles with narcissism and attention-seeking.

Without attempting to make a laundry list, it’s worth noting that some of the hate crime hoaxes and false crime reports have been absolutely boggling — in the sense of “as well planned as the 1983 Brink’s-Mat heist”.

While phoning in hundreds of bomb threats to Jewish Community Centres — first in the US, then globally — Michael Kaydar ran a phone bank out of his home, masking his caller ID using a service called SpoofCard and paying for it using Bitcoin rather than a traceable credit card or PayPal. He routed the calls through anonymous proxy servers overseas, sending the FBI on multiple wild goose chases.

Meanwhile, the bomb threats continued. Jewish care homes and day schools began evacuating with almost routine regularity. The threats were seen as evidence that anti-Semitic fringe groups were emboldened by Donald Trump’s election. It was only when Kaydar accidentally forgot to use his proxy server, disclosing a real IP address — location Ashkelon, Israel — that police finally traced it to a WiFi hub the teenager was accessing through a giant antenna pointing out his bedroom window.

Needless to say, both Israel Police and the FBI let rip with a number of justifiably salty complaints about wasting police time, while a Jewish friend of mine made the bitter observation that Kaydar “had made it harder to live in the world as a Jew”.

Closer to home, Operation Midland was a skein of horrors, which — as it unravelled — cost the Metropolitan Police thousands of man-hours and an as yet unknown sum in compensation to those wrongfully accused of running a VIP paedophile ring.

The investigation itself carried a price tag north of £2.5 million, while former Tory MP Harvey Proctor — who was falsely accused of rape and murder and lost his house and job as a result — won £900,000 (from the Met) for loss of earnings and damage to his reputation. In late July 2019, the entirety of “Operation Midland” came apart, and Carl Beech (a fantasist later convicted of paedophilia) was imprisoned for his troubles.

Worse, a number of public figures — notably Labour’s Tom Watson — bought into Beech’s claims of historic child abuse, giving them oxygen from the floor of the Commons.

In December 2021, meanwhile, actor Jussie Smollett was convicted under US public order legislation for perpetrating a hate crime hoax.

These vast exercises in organised criminality tend to overshadow smaller incidences of the same thing, but be in no doubt that people like Liam Allan (fake rape allegation) have had their lives comprehensively upended.

No one really knows how many reports — as a percentage of all crime reports — are provably false. My pupil-master (an eminent QC and later Supreme Court judge) said 10 per cent was a good rule-of-thumb. He did, however, tell me that way back in 2006 and as anyone who hasn’t spent the last few years living under a rock knows, since then we’ve experienced an immense moral panic about historic sex offences (“Me Too”), an allegedly off-the-scale racist US president, and Brexit.

On that last point, I’m now reasonably satisfied the increased hate crime widely reported from 23 June 2016 onwards and seized upon by the Remain camp after its shock defeat was a classic example of moral panic, and that most of the reports were false.

This is because no evidence is required, only the victim’s subjective feelings. Worse, many reports are not made to police, but to an online portal called “True Vision”, which allows (and encourages) anonymous submissions and also permits the alleged victim to forbid police follow-up. Even when contacted in person, police officers are not allowed to contest an alleged victim’s interpretation of events. They can’t even ask, “are you sure?”

The process goes by the name of “perception-based policing”. It’s got that way we’re encouraging people from minority backgrounds (loosely defined) to audition for respect by being the most insulted person in the village.

Fake hate crimes exist because — across much of the developed world — we’ve made being a victim of what US commentator Josh Slocum calls “heirloom trauma” profitable. That is, we’ve decided it’s acceptable to treat people differently and more leniently as members of a group based on the way that group’s ancestors were treated.

Increased appetites grow by what they feed on, and we are currently subsidising victimhood and taxing resilience. This means more of the former and less of the latter, along with more (and more costly) miscarriages of justice.

This is great and timely commentary. The use of the word 'hate' to describe disagreement (with radicals) is on the rise too, you cant read a newspaper in Canada today without seeing at least one headline (and probably several) claiming that either A) some 'hate' action has been perpetrated by some vague 'far-right hate group' or B) some marginalized community has been targeted by 'hate'. Frankly, its out control. Its really an attempt (as you say) for narcissists to gain attention, but its also a way for radicals to shut down speech opposing them. All sorts of good faith principled opposition to radical ideas and people is now framed as hate, it's simply an attempt to shut people up. Calling out this bad behavior, as you are (and I do too) is really important. Its especially dangerous when state institutions like school boards start using political rhetoric (using the word hate) to describe disagreement.

Much of the "Believe" view of the law reminds me of the old witch trials, if she downs, she was innocent, if she floats, she's a witch