The paradox of polities

The state protects against social predators and is the most dangerous of social predators

This is the fourth essay in Lorenzo from Oz’s series on the strange and disorienting times in which we live, and as with the previous three, the ensuing conversation has been extraordinary.

Of particular note is this response by Simon Cooke in The View from Culllingworth and another excellent short piece from Arnold Kling at In My Tribe.

This fourth piece can be adumbrated thus: States—can’t live with ‘em, can’t live without ‘em.

Housekeeping: I have activated paid subscriptions, and a number of you have put your hands in your pocket so money goes into Lorenzo’s pocket. Do be aware, however, this substack will always be kept free for everyone. I’m vain enough to think that Lorenzo’s ideas are important enough not to go behind a paywall. I want people to read them. So does he.

That means providing benefits other than paywall-dodging for people who donate.

Founders who pay USD$120 will get a free copy of one of my novels (please choose one and write to me with an address; you know who you are). Paid subscribers generally will get exclusive zoom chats with me, Lorenzo, and—if there is enough money—other writers I publish.

Meanwhile, for those who want to “hit the tip jar” and make a one-off payment that isn’t a traditional substack subscription, go here. I’ve been able to set up a traditional blogging tip-jar facility using Stripe, which has stronger free speech protections than the available alternatives.

Once again, the publication schedule for Lorenzo’s essays is available here, and will remain pinned at the top of my substack throughout the publication process. I’ll also link each essay there as it’s published, so it becomes a “one-stop-shop”.

Lorenzo is on Twitter @LorenzoFrom. I’m on the Bird Site @_HelenDale

Both of us will tweet each essay as it’s published. Do subscribe below so that you don’t miss anything, and help spread the word.

Note: at the end of each essay, you’ll find a detailed bibliography and suggestions for further reading.

Ibn Khaldun contra Marx

It’s useful to contrast Marx’s profoundly mistaken delusions about surplus, class, and the state with observations from the first, and greatest, of historical sociologists, Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406).

Ibn Khaldun articulated the fundamental paradox of the state: we need the state to protect us from social predators, but the state is itself the most dangerous of social predators.

Mutual aggression of people in cities and towns is thus averted by the authorities and by the government, which hold back the masses under their control from attacks and aggression against each other. They are thus prevented by the influence of force and governmental authority from mutual injustice, save such injustice as comes from the ruler himself.

The Muqaddimah, I.2.7.

This seeking to have the most effective social predator be one’s protector is a paradox at the heart of state social pacification that can never be solved, just managed more or less badly.

This is notable because, for most of human history, state apparats were not agents of their wider society. On the contrary, those pacified and taxed by the state were often resources for the state apparat.

Rulers were rulers because they were a-top the state apparat. It channelled resources to the ruler, while rulers sought to ensure the agents of the state apparat acted according to the ruler’s will (with varying degrees of success).

Deliberative assemblies with genuine power, including those which developed via the representative principle into Parliamentarianism, are the only path whereby the state apparat becomes, to any significant degree, its society’s agent. And achieving parliamentary democracy doesn’t mean the struggle to ensure that the state apparat is reliably an agent of the wider society has been finally won.

The paradox of polities never goes away, it’s just managed more or less badly.

Even in Parliamentary states, what is the great advantage of empire to a state apparat? You administer people for whom you are not the agent, to whom you are not accountable.

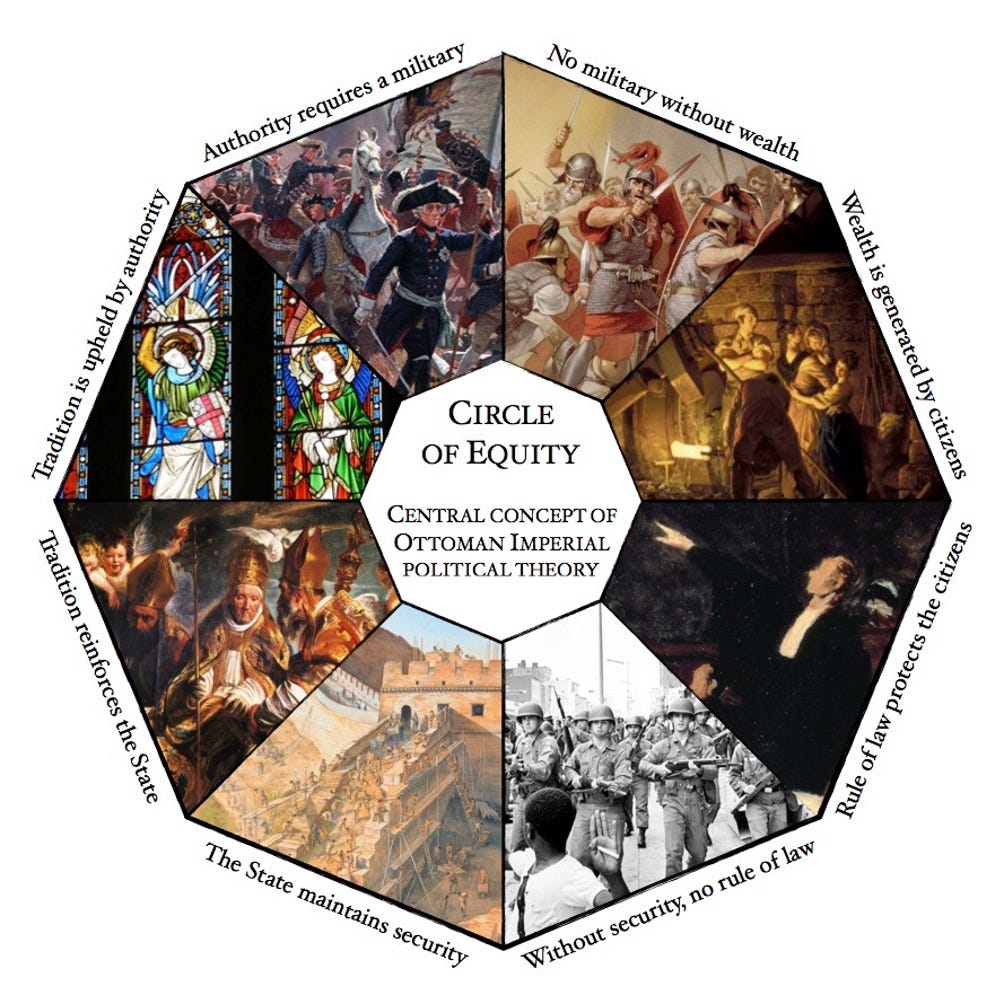

The circle of justice in Islamic political theory, dating back to at least the tenth century, expressed the centrality of the state to social order:

The world is a garden, hedged in by sovereignty

Sovereignty is lordship, preserved by law

Law is administration, governed by the king

The king is a shepherd, supported by the army

The army are soldiers, fed by money

Money is revenue, gathered by the people

The people are servants, subjected by justice

Justice is happiness, the well-being of the world.

Ibn Khaldun has his own version:

[1] The world is a garden the fence of which is the dynasty [dawlah]. [2] The dynasty is an authority through which life is given to proper behaviour. [3] Proper behaviour is a policy directed by the ruler. [4] The ruler is an institution supported by the soldiers. [5] The soldiers are helpers who are maintained by money. [6] Money is sustenance brought together by subjects. [7] The subjects are servants who are protected by justice. [8] Justice is something harmonious, and through it the world persists. The world is a garden...

The Muqaddimah, Bk 1, Preliminary remarks.

Ibn Khaldun was aware, in a way that Marx was clearly not, that the state is the dominant economic actor in any society with a state.

The reason for this is that the dynasty and government serve as the world’s greatest market-place, providing the substance of civilization. …

The dynasty is the greatest market, the mother and base of all trade, the substance of income and expenditure. If government business slumps and the volume of trade is small, the dependant markets will naturally show the same symptoms, and to a greater degree. Furthermore, money circulates between money and ruler, moving back and forth. Now, if the ruler keeps it to himself, it is lost to the subjects.

The Muqaddimah, I.3.40.

Ibn Khaldun talks in terms of the “dynasty” [dawlah] being so dominant, because he lived and wrote in a civilisation where law was dominated by religious scholars and anchored in revelation.

In a situation where rulers have very limited law-making powers (limited to rules for the state apparat itself, say) so political bargains cannot be entrenched in law, states are almost pure structures of pacification-and-domination. Such states came and went while leaving remarkably little distinctive effect on their civilisation’s institutional structures. (This was true of the autocracies of Brahmin civilisation.)

Even so, the class structure of state societies in Islam (or in the Brahmin world) was very different from that in stateless ones. Societies without stored food tended to have flat and permeable social hierarchies, due to a lack of surplus.

The struggle to control the state apparat

The notion that states are subordinated expressions of their societies only has plausibility in situations of relatively stable boundaries, where the long struggle to turn the state apparat into the wider society’s agent has been relatively successful. (It is never fully successful.)

Looking at the fluidity of state boundaries across history, what “society” were states supposed to be expressions of? The bit that stayed within the boundary of the state over time? What was special about it? Was there anything fundamentally different about its relations to the state than, say, contested areas that moved in and out of state boundaries?

When you look at the operation of historical states, the dominant relationship is the other way round. The state apparat dominates the creation and extraction of resources and the mobilising and structuring of social resource flows. The state apparat was typically most thoroughly embedded in the territory it controlled longest, but that reflected gradations of control.

Even in Islamic and Brahmin civilisation, where clerical control of law hugely restricted the institutional effect of rulership, the autocratic fluidity of rulership displayed how much rulerships were not subordinated expressions of their societies, but organised attempts to extract resources from whatever parts they controlled at various times. Particularly, as ibn Khaldun pointed out, they dominated the flow of resources not involved in basic subsistence.

Rulers themselves always have difficulties controlling their own officials: what economists call principal-agent problems. The capacity of Parliaments to provide information to rulers about their own agents was part of the value of Parliaments for rulers. Along with finding out (and bargaining over) what was bothering politically significant people and getting consent for taxes, which made them easier to collect.

Across the long haul of European Christian civilisation, Parliaments went from consent makes taxing easier to taxing only possible if have consent. Bargaining over taxation via Parliaments evolved into bargaining over imposing accountability on the state apparat. The push for putting political bargains into law (which made them worth doing) evolved into imposing accountability on the ruler and his state apparat.

Enduring patterns

Having a Parliamentary tradition turned out to matter when it came to the experience of Marxist tyranny.

The level of domestic Marxist murderousness was much less in countries with Parliamentary histories (Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany), so histories of political bargains being put into law. Or in countries adjacent to same (Albania).

Marxist murderousness was worse, often much worse, in countries with deep histories of autocracy (Russia, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Ethiopia, North Korea), so without a serious history of entrenching political bargains in law. Or, indeed, of law as other than autocratic diktats or directions to officials. Being at war with another state tended to mean less, rather than more, internal murderousness, given the need to mobilise resources for the war effort. (Very coastal postwar Vietnam used the innovative tactic of driving its unwanted human dross into the sea.)

While the content and falsity of Marx’s doctrines matter greatly for the course of Soviet history, and of other Marxist regimes, his analytical framework is as useless for analysing the history of the Soviet Union and other Marxist regimes as it is for understanding surplus, class, states and commerce. By contrast, Ibn Khaldun’s analysis of the patterns for elite dynamics in autocratic regimes works just fine in analysing the history of the Soviet Union:

Stage 1: Group motivated by strongly cohesive group-feeling (asabiyya) seizes power. (Lenin)

Stage 2: The ruler separates himself from the group to establish his dominance. (Stalin)

Stage 3: Group-feeling decays as the elite enjoys, and competes over, the benefits of rule. (Khrushchev to Chernenko)

Stage 4: Group-feeling collapses and the regime is overrun or breaks up. (Gorbachev)

Ibn Khaldun’s analysis centred on the interaction between pastoralist nomads and settled farmers with cities. The state centred on Moscow, and its institutional culture, was created out of that interaction, albeit a distinctive form of it.

It is an analytical mistake to see the Muscovite state as a product of European patterns. The Republic of Novgorod was a classic medieval Christian mercantile city-republic. The realm of the Grand Princes of Moscow was something rather different.

Muscovy was a farming state that was the heir to, and adaptor of, the institutional politics of pastoralist polities. Politically, it was the heir of Tartary, not Kievan Rus. An institutional culture whose path runs through the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and into the Russian Federation.

It is less than startling that the analysis of Ibn Khaldun, a fourteenth century polymath well aware of the dynamics of pastoralist societies, turns out to apply to an industrialised, revolutionary Marxist state half a millennia later, for underlying structures can persist across time.

Moreover, ibn Khaldun was attempting to understand social dynamics in their own terms. This gives him a profound advantage over Marx, whose analysis is driven, and degraded by, his commitment to the transformational future to which his analysis has to point.

To put entire control over the creation of surplus in the hands of the state is to maximise the creation of class hierarchy, not minimise it. As can be seen in every Marxist state.

It is also to destroy any resource-base for resistance to the demands of the ruling revolutionary elite. The delusion that private ownership of the means of production dominates the creation of surplus, and so the creation of class structures—which can therefore be eliminated by ending such ownership—also ensures that Marxist states will be tyrannical states, as full command economies must be.

That the first revolutionary Marxist state, the Soviet Union, reintroduced state slavery via its labour camp system, and then reintroduced an expanded serfdom—by banning workers from changing workplace without workplace permission—was an enabled consequence of the concentration of all production in the hands of the state.

Marx and the intellectuals

By encouraging the view that states are basically “reflections” of their societies, rather than fundamental structuring elements thereof, Marx has encouraged generations of intellectuals not to understand how class structure is created and maintained. He has also encouraged them to discount the difficulties in ensuring a state apparat operates as the agent of wider society.

Claiming that a properly motivated and knowing elite should be given such utterly dominant social power so as to comprehensively transform society is to ensure that the paradox of polities will be managed very badly (i.e., tyrannically). It reverts to a pattern whereby those pacified and taxed by the state become resources for the state apparat. Or, in modern times, the Party-state apparat.

This is true of every single revolutionary Marxist regime as a direct result of their Marxism. The North Korean regime has simply taken this atavism to an extreme and reinstalled the dynastic principle at its apex. Reintroducing slavery and serfdom also fits in with state atavism.

Cults of personality sitting on top of secular theocracies is also atavistic, the modernised version of rule by God-kings. For, where public loyalty is compulsory, only extravagant, even debasing, expressions of loyalty are sufficiently costly to be believed. Hence the divine rulers of the past and modern tyrants’ cults of personality.

Tyrannising struggle

The notion that human existence is all about class struggle has the same murderous and tyrannical implications as claiming that human existence is all about race struggle.

Murderous, because clearly the righteous class or race is justified in eliminating its exploitative, parasitical or otherwise inferior rival(s).

Tyrannical, because it not only strips human groups of moral legitimacy, it strips away the contingency of history—the this-is-what-happened because of what people did—and the could-have-happened-differently if people had acted differently. It strips away the human agency that created that contingency.

Such struggle-theses are thus profoundly anti-democratic. Democracy being rule by the agency of the general populace. By the contingent choices of electorates.

If history is all about class or race struggle, the application of state power becomes not a danger to be managed, but a tool to be correctly directed. One to be judged entirely by its role in that struggle and so to be maximally mobilised to prosecute that struggle. Hence you get the Party-State, where the state is subordinated to a grandiose political purpose and so capable both of pervasive tyranny and mass murder on a grand scale.

Hitler as the secular Satan, the great embodiment of evil, provides progressives in general, and Marxism and its derivatives in particular, with endless cover. The mass murders and tyrannies of Marxism, vaster in extent across time, space and corpses than those of Nazism, recede into the background behind endless invocations of the Holocaust. Progressives can avoid confronting the metastasising of their own tradition.

Without the cover of Nazism, Marxism would stand entirely exposed as the most murderous and tyrannical political movement of the modern era. The cover that Hitler and Nazism is used to provide Marxism is even more striking given that Nazism is so tyrannical and murderous, not because it is so different from Marxism, but because it is so similar.

Imperialism as what states do

Marx also encouraged the misunderstanding of international state dynamics.

Imperialism is simply what states do when they can. As soon as there are states, there is imperialism.

Pastoralists may invade, raid, enslave. To create an empire, however, requires a state.

Imperialism is not a manifestation of a social system, nor an economy. Imperialism is a manifestation of the territorial expansion of state authority. Which every state apparat has an incentive to do, as it increases revenue, standing, authority, and career prospects.

The question is what structures restrain states from acting on those incentives. Typically, the block has been either the power of rival states or the lack of useful revenue from the available territory.

In the post-1945 world, the experience of the horrors of Nazi imperialism in the territory of European states, few benefits from imperial possessions accruing to voters, plus defeat in various anti-colonial revolts, led European states to retreat from direct territorial imperialism.

State apparats switched their colonial efforts from external expansion to internal expansion within national territories, trading the imperial state for a welfare state. A shift from the territorial-imperial state to the social-imperial state. The expansion of international and supranational bodies also created more venues for expanding income and authority. One colonises social space rather than territorial space.

I’ll explore the implications of a shift from territorial to social imperialism in later essays. In the next essay, I’ll consider the deep appeal of Marxism. This appeal has little to do with the accuracy of its analysis of social dynamics and a great deal to do with the sense of meaning and purpose it provided.

This template of meaning and purpose, having infected academe, could and did evolve into new forms of pseudo-knowledge providing similar senses of meaning and purpose, generating networks of motivated vanguard capital.

References

Books

David Frye, Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, Faber & Faber, 2018.

Paul R Gregory and Valery Lazarev (eds.), The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag, Hoover Institution Press, 2003.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N J Dawood, Princeton University Press, [1377],1967.

Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study, Harvard University Press, [1982], 2018.

James C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale University Press, 2017.

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, The Bodley Head, 2010.

Articles, papers, book chapters, podcasts

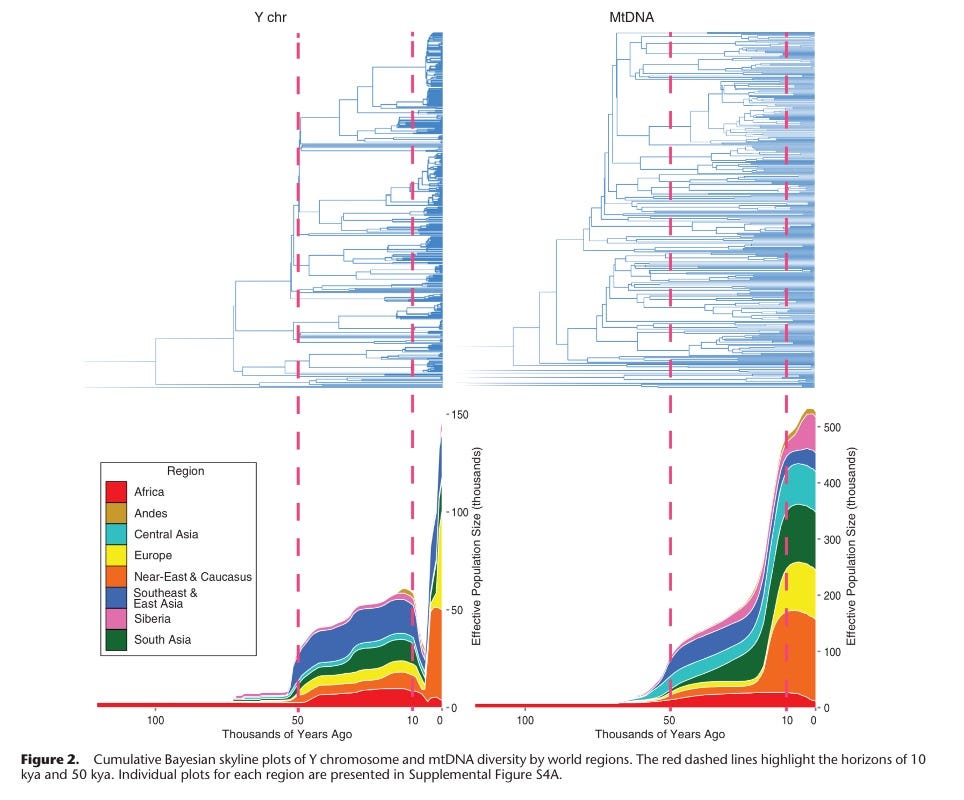

Monika Karmin et al, ‘A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture,’ Genome Research, Apr. 2015, 25 (4):459–466.

Xavier Marquez, “A Model of Cults of Personality”, APSA 2013 Annual Meeting Paper, Last revised: 26 Aug 2013.

Xavier Marquez, “Two Models of Political Leader Cults: Propaganda and Ritual”, Politics, Religion, & Ideology, Volume 19, Issue 3, 2018, 265-285.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency, and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, June 2017, 111, 3. 622-636.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, ‘The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?,’Journal of Political Economy, April 2022, 130, 1091-1144.

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 2018, 9:2077.

Thank you for bringing *The Muqaddimah* to my attention.

That is the best article in this series so far! Well done!