A Crusading Clerisy

Gaining leverage by replicating religion's social role

This is the twenty-fifth piece in Lorenzo Warby’s series of essays on the strange and disorienting times in which we live. The publication schedule is available here.

Many of you are new to my Substack thanks to its “featured publication” status on Substack Inc’s front page this week, and I’ll write a formal welcome to you this coming weekend. However, Lorenzo’s essays are published every week, usually on Thursdays, so now’s your chance to dive in. I strongly recommend going to the pinned post and exploring the rest of his series.

This article can be adumbrated thusly: Marxism isn’t a religion, despite sailing close to the definitional wind. Post-enlightenment progressivism (“Wokery”), however, is definitely a religion.

Do remember, my substack is free for everyone. Only contribute if you fancy. If you put your hands in your pocket, money goes into Lorenzo’s pocket.

Here’s the subscription button, if you’d like to support the writing around here:

Whether Post-Enlightenment-Progressivism (“Wokery”) is a religion is currently the subject of lively debate, and I’ll be exploring this question in the next two essays. However, I draw on legal definitions rather than theological ones because the lawyers are more precise.

Since 1945, universities have expanded, producing many more graduates. The human-and-cultural capital class—people whose social position derives from what’s in their heads—has grown.

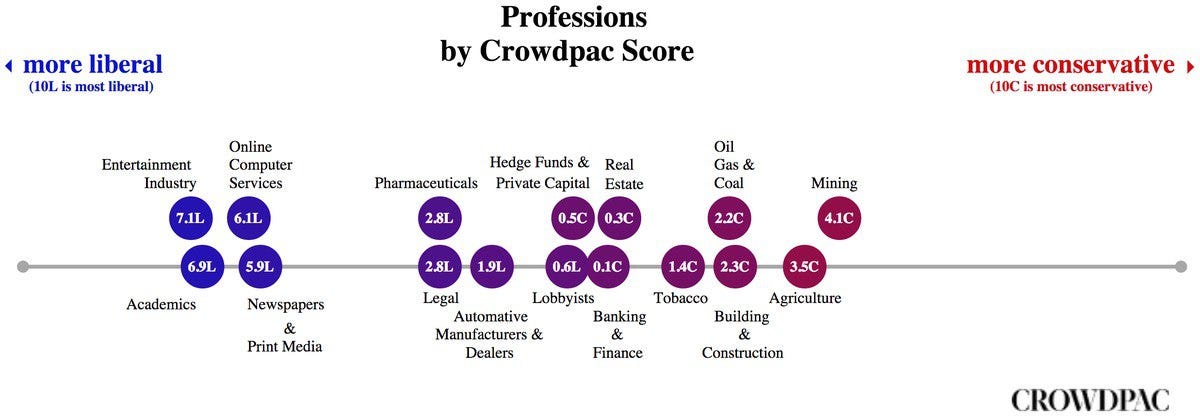

This, plus the evolution of technology, has led to more people with jobs and skills less grounded in physical reality. This pattern is most intense in the epistemic industries: entertainment, media, education, online IT.

Clerics …

Human-and-cultural-capital classes have existed throughout history. The scholar-officials of dynastic China were members. So are the religious scholars of Islam, the rabbis of Judaism, the priests of Catholicism, the pastors of Protestantism and Pentecostalism, India’s Brahmins, Buddhist monks and nuns, the priests and priestesses of any religion.

Short of actually running the state apparatus—as did China’s scholar-officials1—and as do Party-officials in Leninist states2—their most direct path to social leverage, to authority over others, is by controlling what is and is not legitimate to say and do.

It is not remotely a coincidence that dominant members of human-and-cultural capital classes are people with religious authority. Religious authority provides social leverage through legitimating word and action.

This sometimes involves a convergence of interest between the religious class and women (who seek protection via propriety). This was particularly so in Christianity, which sought to impose female-typical sexual behaviour on males.

It’s useful to distinguish between the divine:

the realm of transcendent or otherwise ultimate authority insulated from replicable feedback. (It being the nature of revelation that it is not replicable.)

And the sacred:

things valued in a way such that any trade-off against them is likely to be resisted or refused and may be seen as a betrayal. Contrasts with the profane, where trade-offs are readily accepted.

The notion of the sacred, including a sense of sacredness, underlies taboos, including language taboos. From Christianity—the religion of the sacralised victim—arose the contemporary notion of sacred victims (based on skin colour, religion, sex, sexuality, gender identity). This is used to push taboos and claims to authority over what discourse is legitimate (or not).

Accusations that one is an -ist or a -phobe strip people of any authority to participate in public debate. It’s the modern form of casting out the heretic/blasphemer/infidel, a religious exclude-and-dominate strategy.

As I noted in an earlier essay, the realm of the divine provides grounding for authority as grandiose as one likes. A realm with no replicable feedback, the divine can be used to buttress a wide range of claims.

Hence the appeal of the politics of the transformational future, with its sourcing of moral authority in an imagined future from which there is no feedback. It can be as perfect as one wants. It provides a new basis for age-old patterns of authority.

The politics of the transformational future is not merely a religion-substitute, however. It is functionally religious. This is even more so when we don’t require religion to incorporate the supernatural. It’s notable that US attempts to provide a legal definition of religion wrestle with whether Marxism is a religion.

Marxism’s notion of history as having a telos, a proper direction—it aims at the completion of man’s self-creation—overlaps with many religious ideas. So do the division of labour and commodification, which create an ontological Fall that alienates people from their creative nature.

Marxism is covered under the following suggested legal definition of religion, drawn from US jurisprudence:

… a comprehensive belief system that addresses the fundamental questions of human existence, such as the meaning of life and death, man’s role in the universe, and the nature of good and evil, and that gives rise to duties of conscience.

By contrast, Australia’s High Court (HCA) requires religion to incorporate the supernatural, which excludes Marxism. The UK Supreme Court later came to agree with the HCA, though it prefers spiritual or non-secular to supernatural, meaning:

… a belief system which goes beyond that which can be perceived by the senses or ascertained by the application of science.

Once one adopts standpoint epistemology—including the claim there are oppressive structures only certain people can see—then one has wandered outside a shared natural world. That Marx built on Hegel and poured the spiritual into the social makes it easy—especially if one re-engages with Hegel, or builds on such re-engagement—to shift Marx’s dialectical oppressor-oppressed template in a religious direction.

A lesson from Ancient Rome and Medieval Islam

Post-Enlightenment Progressivism (“wokery”)—the currently dominant form of the politics of the transformational future—performs many religious functions.

It has the same role in government, non-profit, and corporate structures that Christianity did from the reign of Constantine (r.306-337) onwards in the Roman Dominate’s bureaucracy. It provides—as discussed below—a selection mechanism (pick those who agree), a coordinating mechanism (operate off a shared playbook), and an aggrandising mechanism (generates moral projects). Like C4th and C5th Romans, we live in an age of expanding bureaucracy combined with the collapse of an existing religious order.

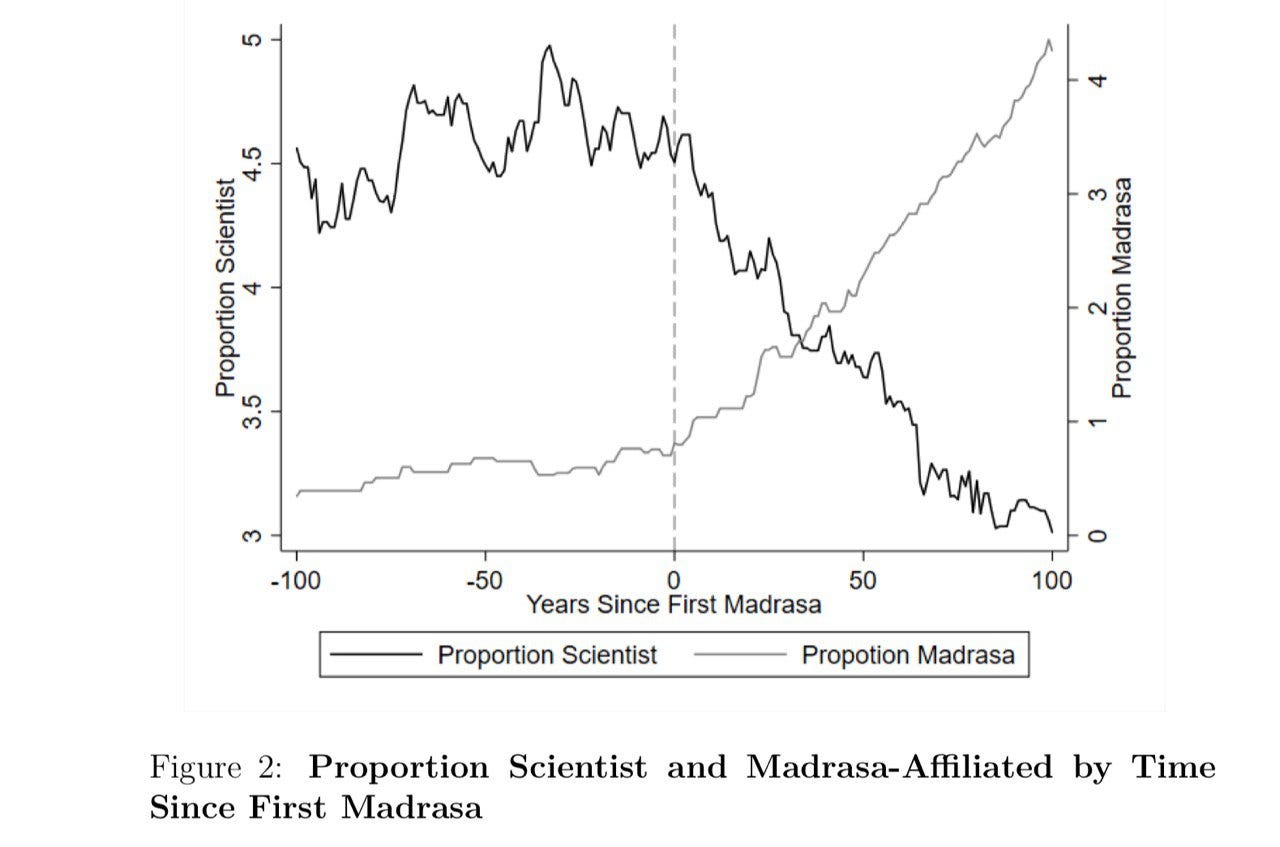

Post-Enlightenment Progressivism is also performing the same role in universities and schools that al Ghazali’s Asharite theology did in the madrassas of Middle Eastern Islam from the C11th onwards. It has the same anti-scientific effects, thanks to moral authority claims trumping knowledge.

Islam provides a particularly stark example of how a civilisation can cripple its own scientific successes. Classical Islam (from the C7th to the C10th) was the “in-the-middle” civilisation, so able to mix-and-match Greek and Indian mathematics, science, and philosophy. It produced a remarkable surge in scientific discovery and dissemination. When Islam’s contemporary defenders make this point, they’re not lying.

Then came al Ghazali’s synthesis of Asharite theology. He argued there is no inherent structure to the universe, merely the habits of God as He creates the universe at every instance. When allied to the claim that the Quran (as the direct Word of God) was uncreated and outside time, this made religious knowledge much more profound than mere interrogation of reality. His synthesis became dominant within Sunni Islam and was promulgated in its expanding madrassa networks.

Science’s loss of standing and resources meant that Islamic innovation and discovery became a shadow of its former self.

This rejection within Sunni Islam of an inherent structure to the universe contrasts with Aquinas’ and Maimonides’ Aristotelian syntheses. Their argument—that God had created a rational world capable of explanation using scientific laws—was accepted within Latin Christendom and Judaism respectively. Mind you, both had to overcome significant opposition, including the claim that accepting an inherent structure to the universe infringed God’s omnipotence.

Ironically—emphasising how much Islam’s wound was self-inflicted—both Aquinas and Maimonides built upon the work of Islamic Aristotelians, especially ibn Rushd (aka Averroes). Aquinas referred to him as The Commentator, while Aristotle was The Philosopher. Aquinas’s synthesis of Aristotelianism and Catholic doctrine encouraged Scholastic thinkers to investigate natural phenomena, which meant Western science began to develop just as Islamic science was withering.

Blocking bargaining

If law is based on revelation—as is Sharia—then it inhibits legislating for political bargains. This makes explicit political bargaining—required for non-autocratic politics—less likely to be worth the effort.

The only pre-1900 Islamic republic, the corsair city-state of Sale, was founded by Morisco refugees and copied Christian self-governing cities. The triumph of Brahmin law-based-on-revelation—a key element in its successful response to Buddhism, Jainism and the other Sramana movements—meant that Classical India’s Gana-Sangha republics were replaced by autocracies.

Democracy is a system of government where citizens can participate in political bargaining by the mechanism of voting. Clement Attlee defined democracy as “government by discussion”.

The politics of the transformational future—including Post-Enlightenment Progressivism—is hostile to open discussion. Precisely because it seeks to police discourse in the name of morally trumping activism, it makes effective political bargaining and alternative choices—including alternative democratic choices—illegitimate.

These anti-bargaining—so anti-democratic—effects are magnified when social-status and social-leverage patterns become entrenched within the media class. As a veteran journalist noted in his exposure of the Russiagate nonsense:

Walter Lippmann wrote about these dangers in his 1920 book Liberty and the News. Lippmann worried then that when journalists “arrogate to themselves the right to determine by their own consciences what shall be reported and for what purpose, democracy is unworkable.”

This damages a society’s ability to talk to itself, undermining both accountability and its capacity for broad-based political bargaining.

Selecting for religious modes

The massive expansion in the human-and-cultural capital class that occurred as a result of the postwar education boom—and the increased bureaucratisation of just about everything—came to select for status-and-social-leverage-strategies that use religious modes of authority.

Marxism provides a working template to motivate and coordinate such strategies. Various ideological entrepreneurs provided the means to update and adapt that template.

Lenin’s model of operational Marxism3 demonstrated how well structured the politics of the transformational future is for bureaucratic aggrandisement:

The totalitarian state had its origins in War Communism, which attempted to control every aspect of the economy and society. For this reason the Soviet bureaucracy ballooned spectacularly during the Civil War. The old problem of the tsarist state—its inability to impose itself on the majority of the country—was not shared by the Soviet regime. By 1920, 5.4 million people worked for the government. There were twice as many officials as there were workers in Soviet Russia, and these officials were the main social base of the new regime. This was not a Dictatorship of the Proletariat but a Dictatorship of the Bureaucracy.

Figes, Revolutionary Russia 1891-1991, p.154.

Social justice generates moral projects that aid the welfare state’s colonising of society. Hence also the elevation of discourse as the supreme vehicle of moral action and belief as the supreme marker of moral status.

If you think people are good or bad depending on their beliefs, there’s an excellent chance you’re a self-righteous shit. You will naturally slide into supporting a social regime of moral intimidation and censorship, and to argue that error-has-no-rights. If believing X makes you a good person, then believing not-X must make you a bad one.

The claim that belief determines goodness is toxic nonsense. Behaviour is what shows character. It is perfectly possible for a good person to have some horrid beliefs if, in practice, he never acts upon them. Similarly, it is perfectly possible for a wicked person to profess all sorts of noble beliefs and yet still engage in evil behaviour. There is an entire set of persons who do precisely that. Activism empowers and attracts them.

Alas, beliefs-determining-worthiness has an appealing simplicity and comes naturally to many intellectuals. It makes it much easier for them to be the most noble people around.

Selecting for conformity

The more a social milieu lacks character tests—and the weaker its reality tests—the more unconstrained selection-by-approval is likely to become. Without constraining reality and character tests, the efficient level of self-deception also increases, making it easier to rationalise and moralise self-interest.

Character and reality tests are constraints on self-deception because they increase error costs. You take away or minimise those constraints, and self-deception is going to go up. Hence the propagation of pseudo-knowledge in academe and the way commentators and bureaucrats seem able to survive any amount of forecasting, analytical and public policy failures—provided they play to the correct status and in-group markers.

Industries that deal in human imaginings are more prone to select for views that are rhetorically powerful, rather than evidenced.

Expanding bureaucracies provide incentives to develop and propagate beliefs grounded in unreality. As intimated above, prestige opinions and luxury beliefs based on commitment to the future, to social justice, simplify selection procedures. Only those who accept the belief system, the current social justice discourse taboos, the current prestige opinions and luxury beliefs, need apply.

Diversity statements—ubiquitous in academic appointments—perform this simplifying-selection role. They also direct people to engage in, and so support, prestige-opinion and luxury-beliefs status games. To accept non-believers would imply the legitimacy of non-belief, which would mean prestige opinions were just ordinary opinions that confer no status.

Those actively seeking to entrench this normative system have particularly strong incentives to select fellow believers. The larger such belief networks become, the more folk play (and mutually support) a shared status game: this is what the smart and good believe. This simplifies coordination within bureaucracies. If everyone is operating off the same belief system, then convergence in action and response can be reached more readily.

The loyalty and coordination advantages of adherence to a common belief system is why autocracies reliant on mining wealth (silver, oil, etc) for revenue have tended to be overtly religious. This was true of Catholicism in Imperial Spain, is true of Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabism, and the Russian Federation’s Orthodoxy among ruling siloviki. Adherence—particularly to beliefs that seem mad or weird to outsiders—signals loyalty, and so means one gets the goodies ruling elites hand out.

Peter Thiel’s analysis of the “tech curse” in California as having siphoned the Tech Boom’s intense—but narrow—returns into public-sector benefits and highly-rationed real-estate, dovetails with his suggestion that “wokery” is the tech boom’s Wahhabism.

What we see in California is not a model of governance created by the tech boom. The narrowly-sourced riches from the tech boom have enabled it to be done extravagantly.

Favouring selection of members from sacred-victim groups signals adherence and makes it easier to establish patronage patterns. Destroying signals of competence and capacity thanks to such identity-group-based selection is corrosive, even dangerous, for the wider society.

But it’s a useful mechanism for protecting and propagating adherence to status and social-leverage strategies based on correct-beliefs-as-signals. Strategies that—with sufficiently high levels of self-deception—can be followed with great sincerity. Sincerity, of course, is a well-known secret of success.4

References

Books

Scott Atran, In Gods We Trust: The Evolutionary Landscape of Religion, Oxford University Press, [2002], 2004.

Christopher I. Beckwith, Warriors of the Cloisters The Central Asian Origins of Science in the Medieval World, Princeton University Press, 2012.

Orlando Figes, Revolutionary Russia 1891-1991: A Pelican Introduction, Penguin, 2014.

James Hannam, God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science, Icon Books, Allen & Unwin, 2009.

Ira M. Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, [1988] 2014.

Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity & Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale University Press, 1997.

Stephen Smith, Pagans & Christian in the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the Potomac, Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2018.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

Edward J Watts, The Final Pagan Generation, University of California Press, 2015.

Articles, papers, book chapters, podcasts

Scott Atran, Robert Axelrod, Richard Davis, ‘Sacred Barriers to Conflict Resolution,’ Science, Vol. 317, 24 August 2007, 1039-1040.

Eric Chaney, ‘Religion and the Rise and Fall of Islamic Science,’ Working Paper, March 2, 2023.

Eric Chaney, ‘Religion and Political Structure in Historical Perspective,’ Working Paper, October 2019.

Ben Clements, ‘Defining Religion in the First Amendment: A Functional Approach,’ Cornell Law Review, Volume 74, Issue 3, March 1989, Article 4, 532-558.

Ryan Grim, ‘The Elephant in the Zoom,’ The Intercept, June 14 2022.

Jonathan Haidt and Jesse Graham, ‘Planet of the Durkheimians, Where Community, Authority, and Sacredness are Foundations of Morality,’ December 11, 2006. https://ssrn.com/abstract=980844.

Rob Henderson, ‘Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class—A Status Update,’ Quillette, 16 Nov 2019.

Kim Hill, Michael Barton, and A. Magdalena Hurtado, ‘The Emergence of Human Uniqueness: Characters Underlying Behavioral Modernity,’ Evolutionary Anthropology, 2009, 18:187–200.

Ann Krispenz, Alex Bertrams, ‘Understanding left-wing authoritarianism: Relations to the dark personality traits, altruism, and social justice commitment,’ Current Psychology, 20 March 2023.

Jacob Mchangama, ‘The Sordid Origin of Hate-Speech Laws: A tenacious Soviet legacy,’ Hoover Institute, December 1, 2011. https://www.hoover.org/research/sordid-origin-hate-speech-laws.

Ian E. Phillips, ‘Big Five Personality Traits and Political Orientation: An Inquiry into Political Beliefs,’ The Downtown Review, Vol. 7, Iss. 2 (2021) .

Harold Robertson, ‘Complex Systems Won’t Survive the Competence Crisis,’ Palladium: Governance Futurism, June 1, 2023. https://www.palladiummag.com/2023/06/01/complex-systems-wont-survive-the-competence-crisis/

Manvir Singh, Richard Wrangham & Luke Glowacki, ‘Self-Interest and the Design of Rules,’ Human Nature, August 2017.

Richard Sosis and Candace Alcorta, ‘Signaling, Solidarity, and the Sacred: The Evolution of Religious Behavior,’ Evolutionary Anthropology, 12:264–274 (2003).

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136.

Peter Thiel, ‘The Tech Curse,’ Keynote Address, National Conservatism Conference, Miami, Florida, September 11, 2022.

J. Watanabe, J. and B. Smuts, ‘Explaining religion without explaining it away: Trust, truth, and the evolution of cooperation in Roy A. Rappaport’s “The Obvious Aspects of Ritual,” American Anthropologist, 1999, 101:98-112.

Daniel Williams, ‘The marketplace of rationalizations,’ Economics & Philosophy (2022), 1–25.

The weakness (extending to active suppression) of religious authority in Legalist-Confucian China is likely connected to government appointment-by-examination providing a much more direct source of authority for the human-and-cultural-capital class.

Leninist states are famously, often brutally, hostile to religious authority. Contemporary Post-Enlightenment Progressivism (“wokery”) is more hostile to Christianity, with its heritage of authority within Western civilisation, than to other religions.

Lenin’s seizure of power also rescued Marx from obscurity.

The secret of success is sincerity. Once you can fake that you’ve got it made. Jean Giraudoux and George Burns.

From note 2: "Post-Enlightenment Progressivism (“wokery”) is more hostile to Christianity."

The irony of course, is that wokery is fundamentally Christian in its values. Christians believed in equality, but it was equality of souls, equality before God. Christians did not believe (as nobody believes) that people are equal in life, nor that they can be made equal. Woke is what happens when the instinct of equality, cultivated over two thousand years, loses its belief in God. Nietzsche warned of this very thing over 100 years ago. Yet Nietzsche appears to have had little effect on the culture of atheists and secularists.

More brilliance here - Selecting for conformity - removing character as a selection issue is an evolutionary process that makes our world an ever shittier place