JudgeGPT is in Da House

“The dog ate my homework!”

Maybe Judge Kemp only identifies as a judge, because the farrago of nonsense he’s managed to produce in the Peggie matter is, well, a sight to behold.

Industry news/gossip magazine Roll on Friday—otherwise known as the “orange time-suck” among City solicitors—has a handy run-down of the most egregious fake quotations, selective editing, and incorrect citations. It’s a concise one-stop-shop for Peggie errors, although they’ve already had to add to it since it was published yesterday.

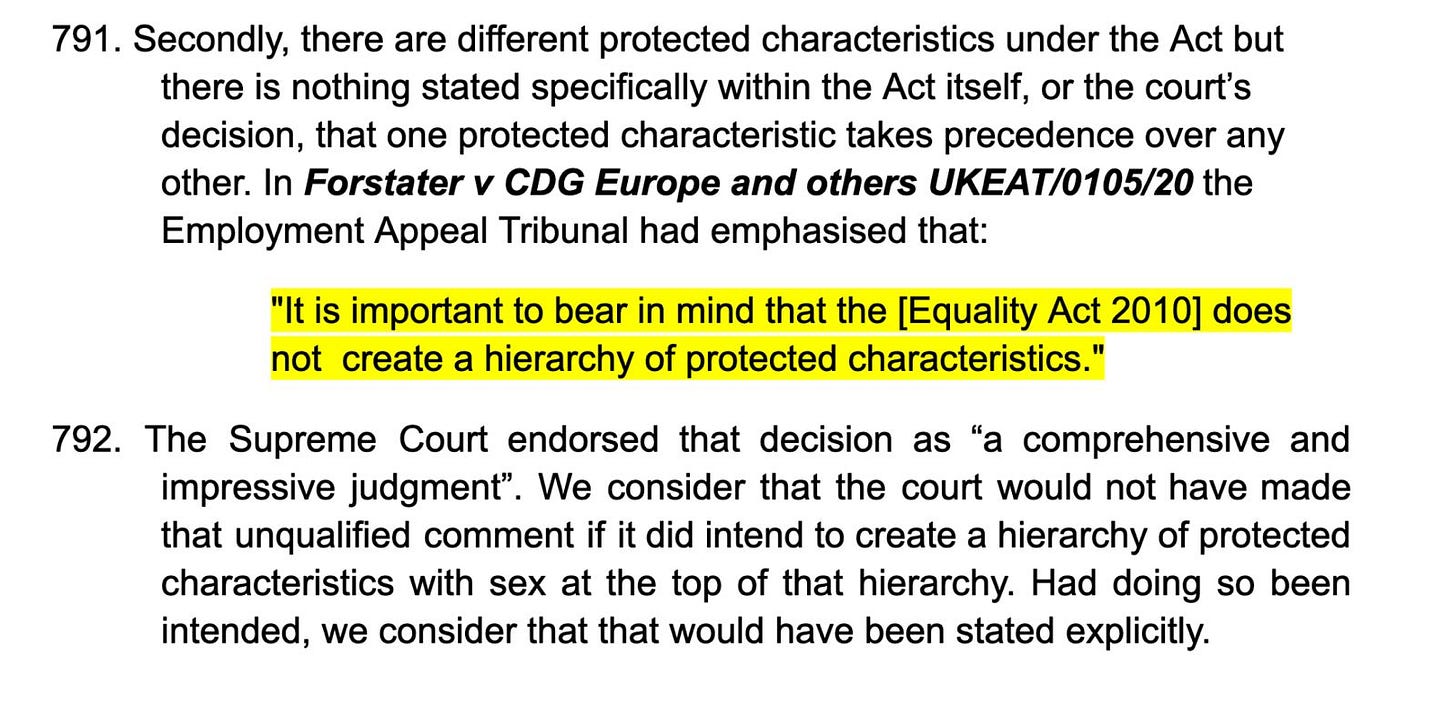

The situation is far more serious than the single—and that was bad enough—fake quotation from Forstater, since corrected by means of what lawyers call “the slip rule”. Notably, the corrected quotation does not support the point Judge Kemp wanted to make, rendering the passage nonsensical.

The slip rule or procedure—something many of us have seen in practice—exists to fix typos, wrong page/paragraph numbers, misspellings. One common error I remember from my pupillage days is fat-fingered judges leaving the “o” out of county in “County Court,” which of course litters the judgment with “Cunty Court”. Yes, everyone laughs and says “typo,” but things like this do have to be fixed.

The Roll on Friday piece notes that the Peggie opinion presents “a summary as if it was a quote from a judgment,” something that “appears to be a recurring issue.” This, as most people know by now, is a hallmark of AI.

I can’t prove that Judge Kemp used ChatGPT or Grok or a bespoke AI made available through the Judicial Office, although my suspicions are strong on this point. As an associate back in the oughts (a special kind of pupil barrister who works for a judge in a superior state or federal court in Australia), I’ve drafted multiple legal judgments. I have a good idea about what goes into them.

I also don’t know if Judge Kemp is on the transactivist side of this particular debate. I do know, however, that the judgment is dreadfully written and full of woolly reasoning, and—as other people have pointed out—all the errors tend in one direction.

I’m now going to set out what I think has happened, with the caveat that I could be wrong—something no-one will know until the appeal is heard and an opinion handed down.

Forms, precedents, and pleadings

Lawyers—when we’re in practice, and even as academics—make extensive use of in-house banks of “styles” (Scotland) or “precedents” (England) when drafting contracts, pleadings, debt instruments, corporate structures, legislation, trusts, wills etc. These represent the accumulated wisdom of one’s firm, usually over decades and even centuries. Some of them go back to antiquity (eg contracts of insurance and reinsurance, which have roots in “bottomry loans” developed by Roman notaries). If, as an employed solicitor, you draft something useful that works well for a client or clients, it belongs to your firm, not you—the usual rule with intellectual property produced “during the course of employment.”

There are also companies that provide searchable banks of styles or precedents for a fee, and firms subscribe to them. Probably the most famous of these is PLC, “Practical Law Company”. One of course modifies the styles or precedents in one’s “firm bank” as necessary for each individual client. This is a legal draughtsman’s key skill, and is cognate with other forms of high quality technical writing, and even writing more widely. Unsurprisingly, it’s something I enjoy.

The problem with AI

Judge Kemp has—I think—treated his AI tool the way a solicitor or barrister treats a firm or chambers style/precedent/pleading bank. However, to state the bleeding obvious, an AI tool does not represent the accumulated wisdom of the legal profession over the past 2K+ years, or even the accumulated wisdom of a single law firm.

Like a lot of technical innovations in their early stages of development, AI is in large part flim-flam. Over time, the useful and accurate elements may take over from the flim-flam, but we are nowhere near that point yet. I’ll also note that Judge Kemp is over sixty, and often took notes during the hearing longhand. This is, shall we say, not a good sign.

Without making excuses for Judge Kemp, I wish to tell on myself a bit here when it comes to AI and how tempting it is to make use of it, even for those of us who should know better.

AI hallucinations

As most people know, search engines have largely turned into woke mush, littered with inaccurate AI summaries. It’s often impossible to find things that one knows to exist out in the wild.

I got very angry last week when Google refused to find me a piece on how Australia has raised its average national IQ thanks to selective immigration, a contrast with every other developed country. I have an exceptional memory for technical detail. I knew what I’d read, and could repeat many of the piece’s conclusions. Repeated searches with varied search strings got me nowhere, no matter how many pages of search results deep I went.

Obviously—as you can see from the link above—I found it. However, I did so because—in despair—I used SuperGrok. I get SuperGrok free with my premium blue tick on Twitter/X. SuperGrok found the article within minutes, after a couple of queries from a rank AI amateur (ie, me). This made me more favourably disposed towards it than I perhaps otherwise should have been.

Foolishly, I then used SuperGrok to do some research on the period I was writing about for my Rage of Party review, which was published on Tuesday this week for Law & Liberty, the magazine where I’m Senior Writer.

What I’m about to say next will make more sense if you read that review, but suffice to say the book is a well-written account of the period 1688-1725 in first England and then Britain (ie, including Scotland after 1707). Among other things, it covers the development of political parties in their modern form, a subject of genuine and global interest. Before that period, what can look like modern political parties in places as diverse as Ancient Rome or Medieval Poland routinely degenerated into civil war or something close to it.

I was keen to get more detail about Jonathan Swift’s writings on immigration policy in the lead up to the 1710 general election. And me being me, I checked the figures SuperGrok gave me, because despite my reputation as a writer and lawyer, I’m actually what the kids call a “shape rotator”. It’s just that my family already had an engineer (my first choice of profession), so dad sent me off to law school. I’ve also had the embarrassing experience of citing a paper that failed to replicate, something I was perfectly capable of checking (the dataset it used was public) in R.

SuperGrok’s figures were correct.

However, I did not check the quotation from Swift that SuperGrok spat out.

It was only when I was doing the final editorial pass that the niggling feeling I was getting about the Swift quote niggled me enough to look it up in Rage of Party. And lo! SuperGrok had hallucinated a Jonathan Swift quote. I swapped in the correct quote (included in my review) and then filed my piece, breaking out in a cold sweat borne of sheer terror as I did so.

I probably only noticed because I’d just finished a book about the period and I’ve read a lot of Swift over the years. I’m familiar with his style.

My point is this: if anyone is going to Hell for the sin of excessive scrupulosity it is me, and I very nearly let an AI drop me right in it. So—without making excuses for Judge Kemp, because I realise this is bad—I can also see how the Peggie foul-up may have happened.

To be quite frank, I think AI is going to rot a lot of people’s brains and stop a lot of other people from learning things properly before we get a proper grip on it.

Anyone who cares about the rule of law should be deeply troubled by the use of AI in producing judgments. If this had been a precedent-setting court the implications would be serious, and if it were a lower profile case it’s highly unlikely anybody would have even noticed.

FWIW, I don't think Judge Kemp is a transactivist; I think he is an old school sexist, or MCP as we used to call them. Amazing how such men have so much in common with transactivists, isn't it?! Replete also, in the passage about lipstick and speaking in modulated feminine tones signalling woman, with that faint whiff of gampiness.