Mismanaged Analogy

Empires also have internal failures

Most of the time, Lorenzo & I like the books people send us for review. Sometimes, however, we finish up with a stinker. Lorenzo reviews one such below.

Lorenzo and I will be having a Chatham House Zoom discussion for paid subscribers this Sunday December 22nd at 10 am GMT.

Hit the button below if you wish to join us. Christmas jumpers optional (we know some of you are in Australia…).

Zoom Link will go out to paid subscribers the day before.

Why Empires Fall: Rome, America and the Future of the West by historian of Rome Peter Heather and political economist John Rapley is not a good book. It attempts to analogise the fall of Rome with the US’s current geopolitical travails. In the process, it reveals itself to be an historical fable written by, and for, an Anywhere elite that cannot look honestly at itself, nor at the social regime it has created and over which it presides.

Often, all they’re doing is showing how clever they are, while passing over more obscure (but equally interesting) historical periods, periods that are, perhaps, actually useful as analogies—just not ones that provide readers with ready mental furniture on which to sit.

One of the advantages of being Australian—of looking at the world from the Southern Hemisphere and the juncture of the Indian and Pacific Oceans—is that it becomes much easier to see through the limitations in (North) Atlanticist perspectives.

For example, it becomes much easier to see through over-claiming about the advantages of the EU. Apart from the experience of Australia’s own post-war prosperity, the postwar economic resurrection of Japan shows that what became the EU was not remotely necessary for a war-devastated economy stripped of its empire to prosper.

Australia’s resource economy also casts strong doubts on the resource-periphery/industrial-core model, or the resource-periphery/financial-core model.1 Then again, comparing landlocked, never had an empire, notoriously wealthy Switzerland with maritime, longest-running substantial colonial empire, Portugal—the poorest country in Western Europe—also does that.

About empire

There are few things which seem to cause more muddy thinking than the notion of empire. The contemporary United States does not have an empire—except in the trivial sense of some island outposts. The US is the Hegemon of a maritime order. That is a very different game.2 Nor was there ever, post-Rome, a Western Empire. There were a whole lot of imperial states, both maritime and landed empires or—in the case of Second Reich Germany—an awkward mixture of both. But they did not, in any sense, form a system with a central imperium.

It was an anarchic system of state competition that generated two world wars in a century—the Dynasts’ War of 1914-1918 and the Dictators’ War of 1939-45. But it had generated world wars before then—the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), the Seven Years War (1756-1763), the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815).

The period of 1815-1914 was striking for lacking such grand, multi-continent, conflicts. Heather and Rapley trying to conjure up a Western empire to make their analogy work is silly.

The maritime order

After 1945, the US maritime hegemony provided a structure whereby the metropoles of shrinking maritime empires could become richer as their empires evaporated. This was a process where membership—or not—of what became the EU was utterly irrelevant to mass prosperity: ask Japan, ask Australia, ask former colonies such as South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore.

One of the muddiest of muddy thinkings about empire is to hold that the maritime empires were some great boon to the economies of the metropoles. This is simply untrue. Empire is, always and everywhere, a state activity. Certain forms of empire could be a boon to state revenue. Outside simple territorial expansion which allowed new territories to be taxed in much the same way as the rest of a land empire, benefits to state revenue came via either the seizure, exploitation and development of [1] trade nodes and/or [2] silver and gold mines. This is a very different matter from the overall effects on the domestic economies of metropoles with maritime empires.

For instance, the flows of American bullion were a boon for the Portuguese and Spanish Crowns. It was a curse for Iberian economies. The “Dutch disease” made local manufactures uncompetitive by being “silver dear,” while it also destroyed the Iberian Crowns’ incentive to negotiate with—or even pay much attention to—local commercial interests. Contrast how Swiss wealth has rested on very careful attention to the needs and opportunities of commerce.

The lack of mass domestic economic benefit from empire is precisely why the maritime empires were either willing to withdraw from many of their colonies or were unwilling to put in the resources—and/or engage in the methods—required to win various wars in their colonial periphery. Resource flows do not explain Western economic power: certainly not anything that rests on some centre/periphery pattern.

At the height of its people running the largest empire in human history, the income from the Empire was worth maybe five per cent of British GDP and—given the Empire’s military and administrative expense—may have cost more than it provided in income. This also means the great bulk of the British economy had nothing to do with its Empire.3

The majority of Britain’s trade was outside its Empire—rich countries mainly trade with other rich countries—and it’s likely that perhaps half of Britain’s trade with the Empire would have taken place if the Empire had not existed.

Losing the Empire did not mean the trade stopped. It didn’t even mean all the income flows stopped, as much of that was return on investments. Britain found—as all the former imperial metropoles found—that access to US markets, and the US-led maritime order, was more economically valuable—and far cheaper—than its Empire had been. That is why all the former imperial metropoles got richer after losing their maritime empires.

Due to the combination of competitive jurisdictions and the Christian sanctification of the Roman synthesis—single spouse marriage, suppression of kin-groups, law as human, consent for marriage, testamentary freedom, no cousin marriage—European Christian civilisation put the central Homo sapien advantage—non-kin cooperation—on steroids. The resulting development of institutional capacity is why European states ended up dominating the planet.

Institutional development, and culture, were more important (and still are) than trade with the periphery. The EU is in relative economic decline precisely because its institutional structure is not up to US and East Asian/South-East Asian competition. It is nothing to do with external resource flows, or centre/periphery dynamics.

It becomes very clear how Britain could lose or discard its Empire and yet become richer. It is also clear that European imperial dominance was a by-product of European economic achievement and institutional capacity, not a cause of such dominance.

European Powers could conquer so much of the world with what were mostly minor expeditionary forces because European organisational dominance was so great. This implies that what’s happening with those institutions will continue to matter. It’s simply not true—as the authors claim—that Western mass prosperity “was constructed on a flow of wealth from the less-developed world into the West” (p.143) and it is fundamentally innumerate (and economically illiterate) to claim so.

Institutions matter

The centre-periphery distinction is systematically misconstrued in How Empires End, as it is in much of the academic literature. Australia is a valued source of resources not despite being an advanced, developed economy but because it is such. That is, it is a reliable, law-abiding, competitively-priced provider with some of the world’s highest paid miners: highly paid because they are so productive. When it turned out that Australia could dig out coal via highly-paid miners, export it across an expensive waterfront, ship it to the other side of the world, across another expensive waterfront, and deposit it outside British mines more cheaply than those same mines could dig up their coal, those British coal mines were clearly doomed.

The difference between core/periphery is not about who does, or does not, have resources. Europe is still full of mines and farms. So, for that matter is the United States. The core-periphery distinction is about who does, or does not, have well-functioning institutions. The story of Japanese, South Korean, Taiwanese, Singaporean, and Botswanan prosperity are all stories of successful institution-building. You become part of the centre by having the institutions that make you part of the centre.

This kind of muddied thinking is usually due to a triumph of Theory over evidence, helped by not noticing patterns that are less salient to folk looking from a North Atlantic perspective. This is added to the pervasive innumeracy of so much academic analysis and commentary.

It does not help when we get cliches—that go back to Marx—about the unceasing demand of “capitalism” for new markets. (Capitalism is an analytically fraught term that also encourages muddy thinking.)

Most systems have very strong status quo bias. We can see this in the “very ready to say no” regulation—such as of land use—in developed democracies. While it is true—as the authors make much of—that the West as a whole has lost share in (an expanding) world GDP, that is mainly a European phenomenon, as in recent decades the US, Australia, and Canada have maintained their shares just fine.4 What commerce does have is a strong discovery incentive, and its disruptiveness is an easy target for interest group mobilisation.

The longer a social system has been operating—especially the less it has been subject to outside pressure and/or the weaker its internal corrective pressures—the more what political scientist Mancur Olson called distributional coalitions emerge to bleed off resources, forming “social barnacles” that degrade the system. The more bureaucratised the state and society, the more that will tend to happen. This is a very clear pattern in Chinese dynasties, for instance.

Core-periphery

By far the most usefully informative element in Why Empires Fail is the discussion of the interaction between Rome’s imperial core and the periphery around the borders of the Empire. There was never another Roman Empire in the Mediterranean world because the Empire itself spread the capacity to organise states beyond the Mediterranean littoral.

Once the social technology of statehood had spread sufficiently across Europe, the geography of Europe precluded another unification on the scale of Rome. Would-be unifiers ended up in an ultimately fruitless “whack-a-mole” strategic game.

The Hapsburgs, and later the Bourbons, found that there were too many European states able to combine against them. The Ottomans found that Christendom could (eventually) provide too much resistance. Napoleon found that he could not conquer Russia or Britain. The Hohenzollern Second Reich could knock out Tsarist Russia but not France or Britain or Italy. The Nazi Third Reich could knock out France, but not Britain or the Soviet Union. All this without considering the European state system becoming an Atlantic, and then global, state system.

As long as the US had enough European allies—France, Britain and Italy in the Great War; Britain and the Soviet Union in its sequel—it could block any attempt to dominate the European continent. NATO has institutionalised this principle.

In Why Empires Fall, Heather and Rapley tease out how interaction with Rome made the areas on their borders more capable: richer, more technologically advanced, more politically coherent. This is all well and good and has obvious parallels with the modern success of states outside of Europe and the settler Neo-Europes—i.e., the Americas, the Antipodes, Siberia.

This process of successful adaptation started with Japan, spread to the rest of East Asia and further out: including such cases as Botswana, South-East Asia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Indeed, the UAE seem to be in the process of turning themselves into the new Venetian trade empire. Conversely, Latin America’s institutional failures keep it on the periphery, this despite having a longer history of European settlement than North America.5

Unfortunately, much of the rest of Why Empires Fail suffers from (remarkably) getting the history wrong or engaging in unexamined conventionality while analysing data. While their discussion of the expansion in capacity of the areas adjacent to the Roman Empire is sensible and informative, the treatment of the internal dynamics of the Roman Empire is much less impressive.

Calling the ejection of Britain from Imperial Rome “the first Brexit” is just sad. Yes, there had been a British-based rebellion some decades previously, but such rebellions had been a feature of Roman imperial politics since the Year of the Four Emperors in 69.

Britain was abandoned because an increasingly dysfunctional and revenue-stressed Western Empire could no longer spare the resources to protect it. The result was an appalling disaster for Britain—even the country’s cows got smaller after the Romans left. Imperial protection and bureaucratisation had sapped British society’s resilience, and it wasn’t remotely up to the challenges of collapsing trade and barbarian invasions. This was nothing like a coherent British polity deciding to leave the EU—which was more akin to the Henrician Reformation of England leaving the Catholic Church.6

The authors cite Peter Heather’s own The Fall of the Roman Empire on the rural prosperity of C4th Rome, though acknowledging that parts of the Western Empire did not seem to have shared in this (notably Italy and the Rhine provinces). Yet Heather also points out in earlier work that the cities, and especially the local notables, were clearly in retreat.

Such rural prosperity has to be considered along with evidence—such as the Greenland ice core data—for a Roman Empire after the Antonine (165-180) and Cyprian (c.249-c.270) plagues that was significantly less populous and economically vibrant

Even with pottery shards, archeological data from Nettuno in Italy is congruent with a pattern of lower populations—and less economic activity—after the pandemics.

What we are looking at is how many—but not all—rural areas maintained population and local prosperity while the level of general economic integration within the Empire declined.

One of the surprising historical absences in Why Empires Fail is that the authors discuss the effects of the c14th Black Death at some length, yet they ignore the Antonine (165-180) and Cyprian (c.249-c.270) plagues. They acknowledge—but mostly elide—the massive increase in the Roman bureaucracy’s size under the Dominate, even though they do discuss the undermining of city self-government by that expanded bureaucracy.

Under the Dominate, the Roman bureaucracy grew by orders of magnitude. The cosmopolitan mercantile empire—full of self-governing cities—of the Principate had around 300 full-time civil servants (not including the Imperial household). This expanded to around 30-35,000 under the Dominate.

That dramatic expansion had several effects beyond the strangling of city self-government and civil society. It also meant that far more of the surplus created and extracted by taxation was consumed by the Empire’s administration.

The combination of a dramatic reduction in Eurasian trade levels—about which more anon—with much more expensive imperial administration meant an imperial state that was both more complex to manage and less capable. An early sign of this loss of state capacity was the decay of Roman roads: both a symptom, and a cause, of declining trade.

A less capable Empire was then less able to manage exogenous shocks. A metastasising bureaucracy undermined the Empire’s resilience, a process we can see happening in contemporary developed democracies.

Early in the book the authors compare a generally upward tendency in per capita GDP growth in developing countries with the generally downward tendency of the same in developed countries in the period 1983-2020. The implication is that the former is generating the latter, even though [1] the demographics are hardly identical; [2] it is notoriously easier to have “catch up” growth when one is not on the production frontier; and [3] rich countries still overwhelmingly trade with other rich countries.

This notion of external pressure as the problem is also present when the authors argue that replacement of the Parthian Empire of the Arsacid dynasty by the more capable and aggressive Iranian Empire of the House of Sassan in 224 meant that Roman Emperors had to pay more attention to the Persian border, leading to the division of the Empire into its Eastern and Western halves. Maybe.

Yet a much larger bureaucracy meant much higher administrative costs, and managerial complexity, which in itself facilitated dividing the Empire. That the Emperor who most expanded Rome’s imperial bureaucracy—Diocletian (r.284-305)—also attempted to set up the Tetrarchy is, at the very least, suggestive.

That the bureaucracy was now much larger also meant that the Empire became more subject to the pathologies of bureaucracy. Examining the patterns of Chinese history makes one much more aware of these.

Pathological bureaucracy is something that contemporary Western democracies are also struggling with: especially the EU, and the UK. This is an analogy with the late Roman Empire that would be worth exploring, but it passes the authors by.

Misreading the Crisis of the Third Century

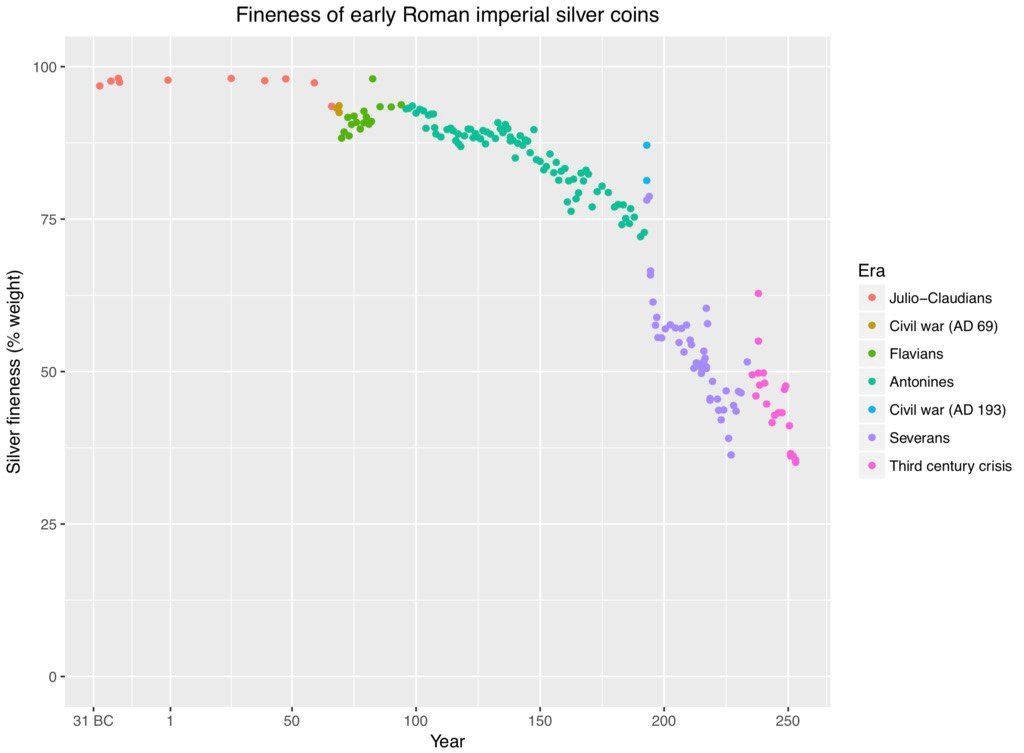

The authors also do not seem to be aware that the collapse in Roman silver production predates the rise of the House of Sassan, as they claim (p.85) that increased military expenditure meant there was not enough silver for the needed coins, leading to their debasement. Indeed, the collapse in Roman silver production helps explain the rise of the Sassanids.

The authors treat the Crisis of the Third Century as a Roman event, largely precipitated by shifts in population pressures on the Steppes. The later shock of the movement of the Huns driving folk such as the Goths westwards in the late C4th can be reasonably analysed in that way, but the c3rd Crisis is a rather different beast.

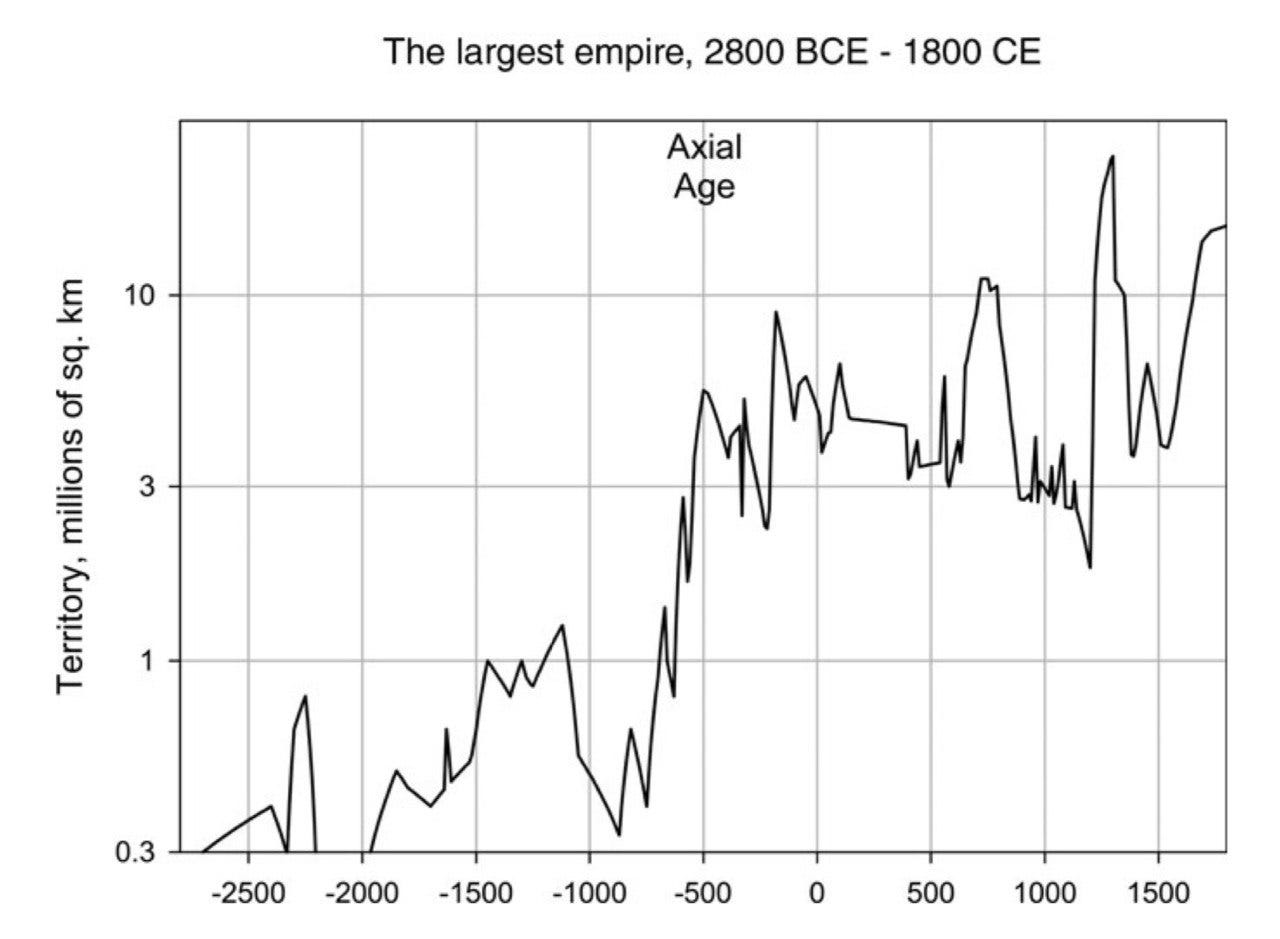

First, it was not just a Roman crisis. There is a wave of imperial collapses and retreats across Eurasia. The Han Dynasty collapses (220), the Kushan Empire fades, the Parthian House of Arsacid is overthrown by their Sassanid Persian vassals (224), various Indian Ocean states collapse or decline.

Second, it was a trade-collapse crisis. The Han-Roman Eurasian trade system was based on export of silk (for horses)7 from China to the steppes—some of which silk was then traded into Iran, the Black Sea, India—and the export of silver from Rome to the Indian trade system.8 The Kushan and Parthian Empires provided links between the two trade systems. This dynamic was the fundamental ballast for a Eurasian trade system that allowed much larger states to arise and maintain themselves.

The basic dynamic for pre-modern states is that tax revenue from land increases linearly: twice as much land of a given quality will generate twice as much tax revenue. Administrative costs increase disproportionately: twice as much territory will require more than twice as much cost to administer, due to factors such as slowness and expense of communication and transport9 plus information management costs.

So, a state system without significant trade will have lots of small polities (“taxing jurisdictions”), as administrative costs rises quicker than revenue across the territory controlled by a state. This puts significant territorial limits on the scale of states.

Trade changes these dynamics. By providing public goods—such as protected marketplaces, safer travel, protection against raids—states can attract trade revenue that (over various ranges) increases faster than administrative costs. Much of this increased revenue comes from increased Smithian specialisation, making land more productive, thereby generating more taxes.

Periods of expansion in trade across Eurasia are periods of larger empires. Thus, the linking up of the East Asian and Indian Ocean maritime trade systems saw a surge of empires in South-East Asia.

The Scythian-Median- Achaemenid Empire (c.653-330BC: see here for problems with the conventional labelling) is the first mega-empire as it—and the Neo-Assyrian (911-609BC) and Neo-Babylonian (626-539BC) Empires—coincide with the rise of the first steppe Empire, that of the Scythians (C9th-C3rd BC), for steppe Empires are trading empires.

Whenever China is unified—so generating more trade—you get imperial expansions. The Qin-Han (221BC-220) unification coincides with the rise of the Roman, Parthian (247BC-224) and Kushan (c.30-c.375) empires. The Sui-Tang (581-902) unification coincides with the rise of the Caliphate (632-750). The partial—but at first highly commercial—Song unification (960-1127) coincides with the Seljuk Empire (1037-1194). The Yuan-Ming-Qing (1271-1912) unification coincides with the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922).

When China dis-unifies in war and strife—so trade falls—you get imperial retreats and collapses.

In pre-modern eras, the periphery confronted a trade/raid choice regarding any imperial centre. Like Chinese dynasties, imperial Rome attempted to encourage the trade option and discourage the raid/invade option—including by also building border walls.

The Antonine (165-180) plague led to the collapse of Roman silver mining, as the mines had gone deeper and deeper and the slaves who kept the mines operating died en masse, resulting in the mines being flooded. This collapse in silver production led to the debasement of the coinage under the Severan dynasty (193-235).

The drop in Roman silver production undermined a key prop of the Eurasian trade system: especially after the drop in population from the Antonine (165-180) pandemic, aggravated by the Cyprian plague (c.249-c.270). There were a knock-on series of imperial collapses, retreats and overthrows across Eurasia. Rome became a less useful trade partner, which made it a more tempting raid/invade target.

Rome itself survived (barely) due to still controlling the Mediterranean trade system.10 But there was a shift to in-kind taxation, which requires a much larger bureaucracy, which in turn absorbs a much larger proportion of a (smaller) surplus, creating a less capable Imperial state far more subject to the pathologies of bureaucracy. The internal dynamics of the Empire matter: it is not just a matter of the rise of the periphery.

The problem with the rising organisational capacity of the Roman periphery—coming to match (but with much lower cost-per-warrior/soldier) the operational efficacy of the Romans in matters military—is that they were better able to contest territory, the zero-sum struggle over which was the income-dominant revenue strategy in the ancient, medieval and early modern worlds. Even more so, when trade was in retreat, as it was—with limited, but generally declining, revivals—from the late C2nd/early C3rd onwards.

Conversely, in the contemporary world, the rising organisational capacity of non-Western states mean more folk to trade with. Yes, that can have implications for particular industries, but it is not remotely a zero-sum series of games. Gains from trade remain a thing. Hence rich countries mainly trade with each other.

If the internal dynamics of the Roman Empire matter, then so do the internal dynamics of modern Western states, and the authors do not seem to want to go there, except in noting the fiscal distress of contemporary welfare states. They especially do not seem to want to examine the dynamics of bureaucratisation—except as an employment-provider—either in Rome or in contemporary Western societies.

Regarding that fiscal distress, the authors engage in what can only be regarded as magical thinking—arguing that if the revenues of the state (perhaps by wealth taxes) were increased, the fiscal stress could be solved. First, OECD figures shows there is a weak positive correlation between the government revenue share of GDP and the level of fiscal distress. From 2014 to 2021, the correlation across 36 OECD countries11 is in the 0.22 to 0.29 range: relatively weak, but persistent—a higher tax share of GDP implies a higher level of public debt.

Second, the contemporary British state commands wildly more revenue than it has ever has in the past. The problem is not a lack of revenue, it is fiscal incontinence. More revenue will just mean a higher level of fiscal incontinence, made worse by shoving even more resources through an increasingly dysfunctional British state—dysfunctional not because of a lack of revenue, but due to expanding bureaucratic pathologies and institutional failures.

Dealing with this will take clear thinking, not what is provided by Why Empires Fail, which reads much more as a comforting “nothing to see in the mirror” missive to an increasingly dysfunctional and incompetent British elite. This includes being dismissive of concerns about migration, with the standard quasi-religious attitude to migration—migration does not fail, people fail migration. (It is not true, for example, that “even unskilled migrants provide more benefits that costs”: p.109.)

Migration becomes an elite marker: only bad/bigoted/ignorant/low class people complain about migration.12 Clearly, there is a market for such elite cognitive comfort food, but it is not an intellectually nutritious one.

There are things to learn from the decline and collapse of the Western Roman Empire, but Why Empires Fail is not the place to find them. Except, perhaps, how elites can fail to see what is in front of their own eyes. The authors make this point early, observing Roman self-congratulation in the year 399. They don’t think it applies to them. They are wrong.

——

References

Jan van den Beek, Hans Roodenburg, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, ‘Borderless Welfare State - The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371951423_Borderless_Welfare_State_-_The_Consequences_of_Immigration_for_Public_Finances

Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900, Cambridge University Press, [1986] 1993.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, Vol.85, No.1, Feb. 1977, 59-77. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/260545?journalCode=jpe

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

John Haldon, Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World 565–1204, UCL Press, 1999.

M.F. Hansen, M.L. Schultz-Nielsen,& T. Tranæs, ‘The fiscal impact of immigration to welfare states of the Scandinavian type,’ Journal of Population Economics 30, 925–952 (2017), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-017-0636-1

Kyle Harper, The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease and the End of an Empire, Princeton University Press, 2017.

Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

W. M. Jongman, J. P. A. M. Jacobs, & G. M. Klein Goldewijk, ‘Health and wealth in the Roman Empire,’ Economics & Human Biology, (2019) 34, 138-150. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30733136/

J.R. McConnell, A.I. Wilson, A. Stohl, M.M. Arienzo, N.J. Chellman, S. Eckhardt, E.M. Thompson, A.M. Pollard, J.P. Steffensen, ‘Lead pollution recorded in Greenland ice indicates European emissions tracked plagues, wars, and imperial expansion during antiquity,’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS) USA, 2018, May 29; 115(22): 5726-5731. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1721818115

Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity & Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale University Press, 1997.

Kristian Niemietz, Imperial Measurement: A Cost–Benefit Analysis of Western Colonialism, The Institute of Economic Affairs, 2024. https://iea.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Colonialism-Interactive.pdf

Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities, Yale University Press, [1982], 1984.

Peter Turchin, ‘A theory for formation of large empires,’ Journal of Global History, (2009) 4, 191–217. https://peterturchin.com/publications/a-theory-for-formatio

Australia also provides a counter-example to many of the criticisms of the c.1980 shift to neoliberalism in economic policy, as its macro-economic performance has been distinctly better—especially since 1992—than that before 1973, without the social divisions neoliberal policies are often blamed for causing. It also avoided both the Global Financial Crisis and the Great Recession.

China, Russia, and Iran—which have nothing in common ideologically—are all autocratic land empires, hence do not “fit” with the US-led maritime order. Democratic peninsular India is an intermediate case.

Not 95 per cent, as expenditure on the Royal Navy had something to do with the Empire.

If China cannot keep productivity growth up, its declining demographics—its labour force has already started shrinking—will lead its economic growth to fall behind the US’s.

In the case of Latin America, the “distributional coalitions” generating social “barnacles” that bleed off resources and degrade economic functioning were built into the institutional structure of the Iberian empires and their successor states.

40 years in the EU seems to have both de-skilled the UK civil service and increased its dysfunctional arrogance by undermining any ethic of service to the British citizenry, especially to the working class.

The low levels of selenium in Chinese soils meant they could not locally breed horses, they had to import them. While lots of Roman silver coins have been dug up in India, none have been found in China.

Diocletian’s Edict on Prices famously tells us that the cost of a wagon of wheat doubled for each 50 miles it was transported.

Despite having fought a border war with the Tang culminating in the Battle of Talas (751), the new Abbasid caliphate was sufficiently concerned by the highly destructive An Lushan rebellion (755-763) that it sent cavalry to help the Tang suppress the rebellion.

Aided by Roman law being very commerce friendly.

There are not sufficiently up-to-date stats for Colombia and no debt stats were provided for Costa Rica.

If necessary, even evidence about appalling sexual exploitation will be suppressed.

It turns out some Roman (gold and silver) coins have been found in China: just not very many.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_coin_hoards_in_China

My favourite insight: "Due to the combination of competitive jurisdictions and the Christian sanctification of the Roman synthesis—single spouse marriage, suppression of kin-groups, law as human, consent for marriage, testamentary freedom, no cousin marriage—European Christian civilisation put the central Homo sapien advantage—non-kin cooperation—on steroids. The resulting development of institutional capacity is why European states ended up dominating the planet."

I hope for an equally succinct insight into the determinants of institutional capacity.