Succession claims and succession games

What is the lineage of a state? or, what Romanitas and Britishness have and the Russkiy Mir does not

I’ve long thought the claim that states are little more than “imagined communities” to be utter nonsense. Indeed, I thought this when I first encountered the argument at university. It’s another instance of what has now become obvious: most of what you learn at university is cobblers, especially if you have the misfortune to read for one of the humanities or social sciences. If you’re lucky, you may learn a foreign language or statistical analysis. Most students are not so lucky.

This is why I’m delighted to publish this piece on state lineages and what feeds into them over time by my favourite independent scholar, Lorenzo Warby (@LorenzoFrom on Twitter, if you wish to follow him on the Hellsite).

The piece explains, among other things, why some forms of colonialism are better than others, and precisely why Ukraine now (and Poland/Finland historically) fight/have fought so hard against Russian colonialism.

When Elizabeth II was crowned on 2 June 1953, the basic structure of her ceremony of coronation dated back to the coronation of the first King of the English, Æthelstan, on 4th September 925, over a thousand years earlier. The sequence of Kingdom of Wessex—>Kingdom of England—>Kingdom of Great Britain—>United Kingdom is a clear case of a state’s continuing lineage.

The Kingdom of Wessex, founded in 519, through successfully resisting the Norse (“Viking”) onslaught, expanded into the Kingdom of England. The Norman Conquest of 1066 changed the English state but did not replace it. Nor did the Dutch Conquest of 1688. (A conquest thoroughly indigenised as The Glorious Revolution; apparently it does not count as a conquest if the right sort of folk asked the conqueror to arrive with an army and if the conqueror’s wife was the presumptive heir to the overthrown monarch.)

The Kingdom of England joined with the Kingdom of Scotland in 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. This also wasn’t a replacement for the existing state, but a union of adjacent states already sharing a common monarch. The Kingdom of Ireland joined the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1800 to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. After the Irish Republic went its separate way in 1922, the state became the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

How can we say this is the continuation of a state? Because across each transition, laws continued, organisations and institutions continued, offices, and officeholders, continued even as the state’s territory waxed and waned.

So, an unbroken state lineage that goes back to the founding of the Kingdom of Wessex in 519. The ending of the Wars of the Roses in 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field is closer to us in time than that battle was to the founding of the state whose monarch it enthroned.

Romanitas

When the armies of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II swarmed into Constantinople on 29 May 1453 and the last Emperor of the Palaiologos dynasty, Constantine XI, vanished into the swirling mêlée of final defeat, what ended there? Nowadays, we say the Byzantine Empire ended, but that is a name given to the state over century after its fall.

Its inhabitants claimed to be Romans. Various Ottoman Sultans—rulers of the conquered city (still known as Constantinople) now their capital—called themselves kayser-i Rûm, Caesar of Rome. They referred to the conquered Greek-speakers as Rum, Romans.

So, the Roman state ended there.

Here we have another continuing state lineage. The Kingdom of Rome—>Roman Republic—>Roman Empire. The Empire of which Augustus (r.27BC-14AD) was the first Emperor and Constantine XI (r.1449-1453) the last.

If we examine why folk want to call the medieval Roman Empire the Byzantine Empire, it turns on a series of transformations.

The first transformation is the shift from the lightly administered Principate — which maintained a tradition of self-governing cities — to the far more heavily bureaucratised Dominate, which steadily strangled the tradition of self-governing cities. The massive increase in bureaucratisation came from a shift to in-kind taxation. The collapse in Roman silver production, which underpinned the whole Eurasian trading system, destroyed the monetised trading system that had provided the revenue base of the Principate. (As it did of a series of other imperial states, including China’s Han dynasty.)

The collapse in the export of Roman silver in return for Asian goods (particularly silk) greatly reduced the trade that provided the revenue “cream” that sustained Eurasian imperiums. This created the Eurasia-wide “Crisis of the Third Century”. A crisis that the Roman Empire was the only imperial state to survive, and even that was a near-run thing. The control of the entire Mediterranean coast gave the Empire a trade-area revenue base far beyond anything that other imperiums had access to.

The second transformation is the creation of Constantinople as the new capital in, and of, the Eastern (Greek-speaking) half of the Empire. It becomes the half of the Empire that survives the collapse of the Latin-speaking Western Empire in the third quarter of the fifth century.

The third shift is the Christianisation of the Empire. This can be categorised many ways, but at its core was shift from an immanent (this-world) to a transcendental (other-world) conception of sacredness, plus the imposition of a feminised sexuality. Christianity sanctified sex-as-commitment, via the extolling of an ethic of chastity for men.

Civilisations typically impose an ethic of chastity on women, to maximise the paternal-reliability of female fertility. Imposing an equivalent ethic on men, including sanctifying the single-spouse marriage that is a necessary support for an ethic of male chastity, was a profound and striking cultural shift.

The modern sexual revolution un-does the Christian sexual revolution in many ways. But a key aspect, accelerated by the rise of dating apps, is a shift from female-typical sex-as-commitment to male-typical sex-as-casual-catharsis. (Which, prior to Christianisation, had been very much the elite Roman male view and social norm.)

The Dominate’s strangling of city self-government aided Christianisation, as local notables stopped having a strong incentive to invest in (pagan) religious festivals as part of running for civic office. The massive expansion in bureaucracy also meant that a shared belief-system that simplified selection (believers only) while generating common expectations — including common moral projects (legitimising bureaucratic activity) — provided bureaucrat-coordination benefits. It is not a coincidence that the first powerful Emperor after Diocletian’s massive bureaucratisation of the Empire was the first Christianising Emperor.

Meanwhile, Orthodoxy now seems to be providing the same coordination service to the siloviki elite of Putin’s Russia. (A coordination service that Post-Enlightenment Progressivism, aka “wokery”, is also providing government, non-profit and corporate bureaucracies in Western states.)

Finally, there was Heraclius (r.610-641) abandoning Latin as the official language of the Empire. Including adopting in 629 πιστὸς ἐν Χριστῷ βασιλεύς, faithful in Christ Emperor (Basileus), as the imperial title.

These transformations of Romanitas were profound. But not so profound as to create a new state lineage. The various survivals that were blotted out from 1453 to 1475 were part of a state lineage that goes back to the notional founding of the city of Rome in 753BC.

Rule of law

The other thing that these two long-continuing state lineages have in common is that they were the two great law-giver civilisations. The world is largely divided into common law jurisdictions, civil (Roman) law jurisdictions, mixture-of-the-two jurisdictions, and states where (regardless of the type of law) rule of law is not so much a thing.

It is quite conspicuous that the three great philosophy-producing civilisations (Greece, India, China) were all conspicuously bad at law. In that sense, philosophy was a displacement activity for something real. This only changed when (if) the societies in question were colonised by one of the two law-giver states.

Philosophy is about abstraction, so involves intense data-compression. Law is about making careful, practical distinctions: as little abstraction (data-compression) as you need and no more. Most philosophical reasoning ends up in some version of a “with one bound, Jack was free” moment as abstraction glides over crucial distinctions. This is a pattern legal reasoning must eschew.

As far as jurisdictional reach goes, the only rival to common law and civil law is Sharia. But Sharia is a mixture of Roman commercial law, sanctification of Middle Eastern agrarian antipathy to interest rates (usury), and the sanctification of pastoralist patterns of polygyny, patrilineal kin groups, and raiding (the rape, pillage, looting and enslaving of outsiders). The much-used phrase in the Quran of “those whom thy right-hand possesses” (ma malakat aymanukum) is clearly a sanctification of sexual predation against outsiders. It is further justified by the example of Muhammad having male captives killed and women and children distributed as slaves to his followers.

Polygyny generates a surplus of unmarried adult males. If the top 5% percent of males have 4 wives each, the bottom 15% of males are shut out of the in-group marriage market. The standard pastoralist response to this imbalance has always been “those people over there have women, steal theirs”, hence their raiding (i.e. raping, looting, pillaging and enslaving) ways. Sharia simply sanctifies this response to polygyny (which, of course, it also sanctifies).

Sharia is also, by far, the most imperial of all legal systems. It has no pre-imperial history, and, as the rules of the Sovereign of the Universe, discovered via fiqh, Sharia is held to apply to everyone. The problem with Sharia is thus not merely its misogyny, but its presumption of rightful Muslim dominion over all things human. (Hence a persistent Muslim tendency to get extra-whiny when their non-dominance becomes salient.) This trait is also why minority forms of Islam—Ahmadis, Ibadis, Ismailis, Alevis, and so on, having perforce given up any claim to domination—generally do not generate problems for others.

Sharia shares with the historic Brahmin-world the domination of law, grounded in revelation, by religious scholars. This has several consequences. One is that political and social bargains cannot be directly entrenched in law. It is possible to create new precedents, it is not possible to create new revelations. This encouraged autocratic government as well as reliance on either kin groups or marrying-in occupation-groups (jati) as mechanisms for risk and inter-generational asset management. Consequently, differentiated law could not be part of the continuing lineage of states. Hence India’s history of dynastic autocracies that came and went and leaving remarkably little institutional impact.

Russkiy mir

Even more than Britishness, Romanitas was not about merely being a state, it was a civilisational identity. This was precisely how a Roman identity could come to operate across diffuse states and even continue after the end of states. Historian Bryan Ward-Perkins was not entirely jesting when he said (in The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization) that the last conquest of the Latin Roman world by a German barbarian warlord was Edward I Longshanks’s conquest of Wales in 1282.

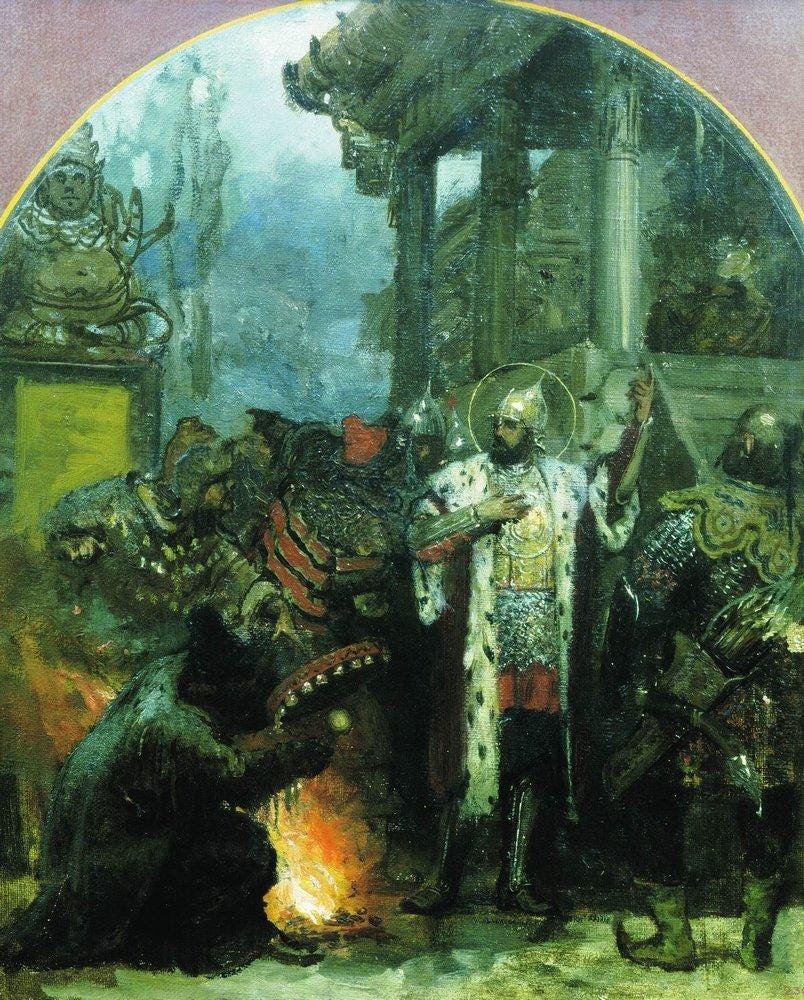

The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 meant that the temporal leadership of the Orthodox world was up for grabs. The Grand Prince of Moscow, Ivan III (r.1462-1505), scion of the House of Rurik, seized the opportunity by marrying the niece of the last Roman Emperor, Sophia (Zoe) Palaiologina in 1472.

Moscow became the seat of the Russian Orthodox Patriarch, but that was due to the success of the state, not due to an inherited state lineage.

Moscow could now claim to be the Third Rome. A claim given even greater weight when Ivan & Sophia’s grandson, Ivan IV Grozny (r.1533-1575), declared himself in 1547 Tsar i Velikiy knyaz vseya Rusi, Tsar and Duke of the Rus. But this assumed imperial dignity was a claim of devolved heirship, not a claim of state lineage. It was very much a civilisational claim, grounded in an Orthodox identity.

So, what was the lineage of the Moscow state? As the last independent Rurikid rulership left standing, it could claim to be in the lineage of the Kievan Rus: Moscow as gatherer of the Rurikid lands. That is certainly the current claim: that Ukraine cannot have an independent identity, because Kyiv is the founding city of the Russian state and the Russian world (Russkiy mir).

But there had been many Rurikid rulerships. If Moscow was the one left standing, the great survivor, then the key thing about it was not likely to be how it was like the others, but how it was different. When one digs into why it was the one left standing, its distinctiveness is its key feature.

Part of the success of the Muscovite Rurikids was the same advantage that, centuries earlier, the Capetians had parlayed all the way to the throne of France. If you keep to strict primogeniture while rival houses are playing the divide-the-patrimony game, provided you can maintain a sufficiently unbroken line of male heirs, and are sufficiently effective at seizing and holding territory, you end up winning the game.

Apply that to a territory-consolidating marriage strategy, and you can be the Hapsburgs. (Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube: let others wage war; thou, happy Austria, marry.) Mind you, a sufficiently dysgenic version of such consolidation-by-marriage can terminate your dynasty.

So, why was Moscow the Rurikid rulership left standing? Because of how it managed the Tartar Yoke.

The Mongol invasion, and subsequent steppe-pastoralist domination, was the shattering transformation of Kievan Rus civilisation. Prior to the Mongol invasion and domination, the Kievan Rus were mercantile Scandinavian warrior elites ruling over (often loosely) a free Slavic peasantry. The rather odd “Buggin’s turn” shuffling of rulerships among Rurikid princes, and being Orthodox rather than Catholic, were somewhat distinctive features, but not startlingly distinctive. Indeed, the creation of the mercantile republic of Novgorod was well within the patterns of medieval European Christendom.

The Mongol invasion and conquest changed this civilisation’s trajectory profoundly. Apart from the sheer slaughter and devastation that were features of Mongol invasion and conquest, Kievan Rus became a civilisation of vassalage to outsiders. The Lithuanians and Poles from the West, the Golden Horde to the East. But vassalage to the Golden Horde would itself be a form of leverage. One that what became the Moscow line of Rurikid princes parlayed from the beginning.

This started with Alexander Nevsky (1221-1263), who fought off the Germanic knightly orders and the Swedes, but operated as a loyal tax-collector for the Golden Horde. Orthodox identity against Latin Christendom would be preserved, by serving the dominion of the (eventually Islamic) steppe pastoralists. Serving the Tartar Yoke also became a way to elevate oneself and one’s family over rival Rurikid princes.

Alexander Nevsky’s youngest surviving son, Daniil Aleksandrovich (1261-1303), became prince of Moscow, the least of his father’s patrimonies. The principle of Daniil’s line became to not divide the patrimony and to seek to become first Rurikid servant of the Golden Horde. Which they eventually did so well as to be both gatherer of the Rurikid lands (apart from those under the control of what became the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) and, after the break-up of the Golden Horde (1502) the conqueror of its successor pastoralist khanates.

The Khanate of Kazan was conquered in 1552, the Khanate of Astrakhan in 1556, the Khanate of Sabir in 1582. The Crimean Khanate, Ottoman vassal and classic pastoralist raiding-and-slaving state, survived until its annexation by Catherine the Great (r.1762-1796) on April 8, 1783. Catherine, by gaining the largest share of the division of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, completed the process of “gathering in” the lands of the Kievan Rus. Mind, she was not a Rurikid but a notional Romanov and did not rule from Moscow, but from St Petersburg.

Kievan Rus heritage

Was what became the Tsardom, and then the Empire, of Russia of the lineage of Kievan Rus? Yes, sort of, but only very thinly do. There is a dynastic and civilisational lineage. But no state lineage, except in the most tenuous sense.

Moreover, if one examines the institutional structure of what became the Tsardom of Rus, it is striking how much it adopted forms and mechanisms from the Khanate it served and then helped overthrow. This even included incorporating the aristocracy of conquered Khanates into its own (after suitable conversions to Orthodoxy, of course). The Khanate institutional patterns are particularly apparent in tax collection and centralisation of administration. The Scandinavian heritage was long since suppressed.

Ivan Grozny’s murderous conquest and absorption of the Novgorod Republic represented a complete suppression of any deliberative assembly’s ability to assert itself against the ruling autocrat. Ivan Grozny did not rule much like a typical European monarch. Timur-e Lang would have found his patterns of brutal massacre much more familiar.

The fundamental strategy of the Moscow line was that pioneered by its forefather Alexander Nevsky: servility and domination. An aping servility towards the dominant Khanate. Centralising domination of those under its control. This pattern of servility and domination has been the classic political pattern of the Russian state and political culture ever since. While, dynastically and civilisationally, it was of the Kievan Rus, in institutions and political culture, the Moscow state was far more a product of the Tartar Yoke.

Eurasian but not Western

Those who claim Russia is a Eurasian state in a quite fundamental sense, are correct. It is only partly European and is not Western. It is not a rule-of-law, parliamentary state. If one wants to be a rule-of-law, Parliamentary state, it is not Russian heritage one would embrace.

This reality that has constantly bedevilled its relationships with all peoples and states on its European borders. All Russia can offer them is domination and that they are willing to pay, and to fight, to avoid.

The Russian world (Russkiy mir) has markers in literature, music, and art which are profoundly impressive by anyone’s standards. The Russian novel is one of the world’s great artforms.

It is in the political culture and institutions that the Russkiy mir fails by comparison with what others can offer. Hence Russian autocracy has been a one-trick pony: conquest and domination is its only strategy. And not one that has worked for it, across the long run of history, given its borders are, in places, now closer to Moscow than they were at the end of Peter the Great’s reign in 1725.

If you are building a civilisation with genuine staying power, conquest and domination is not enough. The Romans and the British provided law: hence their legacies have had far more staying power.

The Russian state, despite a dramatic recent attempt, does not control Kyiv. On the contrary, Kyiv has become a symbol of resistance to the Russiky mir. The state lineage of Moscow is precisely what Kyiv wishes to reject. As, of course, does Warsaw, Helsinki, Stockholm, Vilnius, Tallinn, Riga, Bucharest …

One of the sillier arguments against Ukrainian being a “real” identity is that Ukraine is a borderland. But borderlands are precisely where new ethnic identities are created. Borderlands are where pressures for cohesion can be strongest and clashes of group-identity most intense.

When Ukraine seceded from the Soviet Union, it was divided between those who saw themselves as part of the Russiky mir and those who sought a much more Western identity. Two invasions (2014, 2022) and 8 years of frontier conflict in between have made it clear what the Russiky mir represents, politically: the extinction of any Ukrainian identity.

The willingness of even most Russian-speaking Ukrainians to support continued armed resistance against domination by the Russiky mir is evidence for ethnogenesis before our very eyes: where there is a nation, let there be a state.

On the matter of the Muscovite state being a Christian farming polity that adopted some institutional patterns from pastoralist states, the use of the pastoralist Cossacks as bodyguards, shock troops and order-enforcers increases the congruence.

https://www.youtube.com/live/lcRBh9sJfVM?si=K2HF7SPpsD3PO1Hm

I liked the essay!

Civilization indeed