The B-Team

What happens when entire intellectual movements are led by mediocrities

First, an apology to Lorenzo.

I asked him to read The Wretched of the Earth and he did. Sorry, Lorenzo. Of course, Lorenzo’s loss was everyone else’s gain, and he wrote about Frantz Fanon’s moral monstrousness for the rest of us.

Moral monstrosity is only one thing, though. There’s something else going on.

Frantz Fanon is—not to put too fine a point on it—as thick as mince. I noticed this in 1992 when I had to wade through his writing, although I was helped because—in the edition I had—Jean-Paul Sartre wrote the introduction. Sartre’s preamble was much better written and more smartly put together than anything in Fanon’s book.

I’m not saying this because I agree with Sartre, by the way. The point of his piece was to agree with Fanon. It does what it says on the tin. I’m saying this because part of being an adult is recognising when an opponent makes his case well.

Hilariously, Fanon’s widow later had the preface removed because Sartre backed Israel during the Six Day War, although her prohibition only held until she died. If you buy the book now, you’ll discover Fanon’s publisher has reinserted it.

This was the first instance of something I’ve since encountered multiple times: a female or minority author (usually, but not always, an academic in one of the High Theory ‘disciplines’) is praised far above and beyond their actual talent. It’s easy to spot in Fanon’s case—you’ve got Sartre sitting there in front of you to compare and contrast—but the problem is widespread. It’s typically exposed when you read the French originator of an idea followed by a minority/female (often but not always American) imitator.

It’s generally unwise to write one’s opponents off as daft, so I need to be clear what I’m doing here. I hate to break it to you, but the French originators of a lot of contemporary nonsense—and I take French President Emmanuel Macron’s point that they’ve had far less influence in France than elsewhere—were very smart people. Yes, they were wrong. Academics are notorious for believing all sorts of bonkers crap, a powerful argument for keeping their hands well away from the levers of power. But Foucault, de Beauvoir, Derrida, Sartre, Baudrillard? Bright people with genuine flashes of insight that honest critics must acknowledge.

Cross the Atlantic, however, and the intellectual debasement is near total.

This takes varied forms. Sometimes—I suspect thanks to the American fantasy that one can be taught to write novels—a famous writer is inveigled into believing that he or she can write non-fiction. Two examples that come to mind involve two very great novelists indeed: Toni Morrison and Chinua Achebe. In addition to her novels, Morrison wrote a book called Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, which came out in 1992 (yes, this nonsense has been around for a long time). Whatever you do, don’t read it if you haven’t read any of her novels. You’ll get the wrong idea.

Achebe wrote an academic paper, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” and as with Morrison, my strong advice is not to read it unless you’ve at least read some of his fiction. It, too, will give you the wrong idea about the rest of his writing. There’s a reason I’m not making it easy for you to find either Morrison or Achebe’s efforts at non-fiction.

Such moonlighting isn’t all one way, however, if you think I’m only taking a pop at novelists. Derrick Bell (one of the critical race theory crew) tried his hand at writing science fiction in an academic journal, and terrible science fiction it is, too. His attempt was called “The Chronicle of the Space Traders” and appears in “After We’re Gone: Prudent Speculations on America in a Post-Racial Epoch”.1 And this time, I am directing you towards the publication because you need to know I’m not making it up.

Memo to Derrick Bell: don’t quit the day job.

Academics without redeeming literary talent or a brain to speak of are common in social-justice-world. Here’s Susan Brownmiller combining creationism and conspiracism in a single paragraph:

Man’s discovery that his genitalia could serve as a weapon to generate fear must rank as one of the most important discoveries of prehistoric times, along with the use of fire and the first crude stone axe. From prehistoric times to the present, I believe, rape has played a critical function. It is nothing more or less than a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear.2

If that isn’t bad enough, here’s Ann Jones doing a feminist version of 9/11 was an inside job with side-servings of Barack Obama’s birth certificate is fake:

If this book leaves the impression that men have conspired to keep women down, that is exactly the impression I mean to convey; for I believe that men could not have succeeded as well as they have without concerted effort.3

Note, I’ve deliberately not drawn attention to Andrea Dworkin here. Many critics of feminism encounter Dworkin and—seeing something that presages madness—stop. They shouldn’t. There’s plenty of ineptitude throughout this excuse for an intellectual movement without focussing all one’s fire on Dworkin.

And, to give her credit, no-one is more aware of this than Germaine Greer: she may be a feminist but she’s also honest. In 1995, she took aim at the attempt to “rediscover” historical women writers where (feminists alleged) men had deliberately suppressed their work.

No, not really, Greer argued. In Slip-Shod Sibyls: Recognition, Rejection And the Woman Poet, Greer pointed out that most of these early women poets were actually terrible. Sometimes this was because they had no talent. Sometimes they had talent but were what Greer calls “half-educated,” capable only of mimicking male contemporaries. Worse, without prior knowledge of those male models, their derivative work makes little sense to a modern reader.

In cases of genuine female literary greatness, Greer’s lines of enquiry are still discomforting to modern sensibilities. Often, exceptional women emerged in societies that lacked prejudice against homosexuality—in addition to being slave- or serfdom-based—which meant wealthy, clever women could choose not to have children or did not participate in raising their own children.

One effect of this underpowered scholarship is that an entire important political tradition (feminism) lacks serious intellectual substance. If you want smart, scholarly feminists, you tend to have to go back to the 19th or sometimes the 18th century: people like Harriet Taylor Mill, Mary Wollstonecraft, or Catherine Helen Spence. In the latter case, Spence’s real importance is as an electoral systems analyst (Australia uses her method to elect its Senate).

This is something Steven Pinker has pointed out:

Feminism as a movement for political and social equality is important, but feminism as an academic clique committed to eccentric doctrines about human nature is not. Eliminating discrimination against women is important, but believing that women and men are born with indistinguishable minds is not. Freedom of choice is important, but ensuring that women make up exactly 50 percent of all professions is not. And eliminating sexual assaults is important, but advancing the theory that rapists are doing their part in a vast male conspiracy is not.4

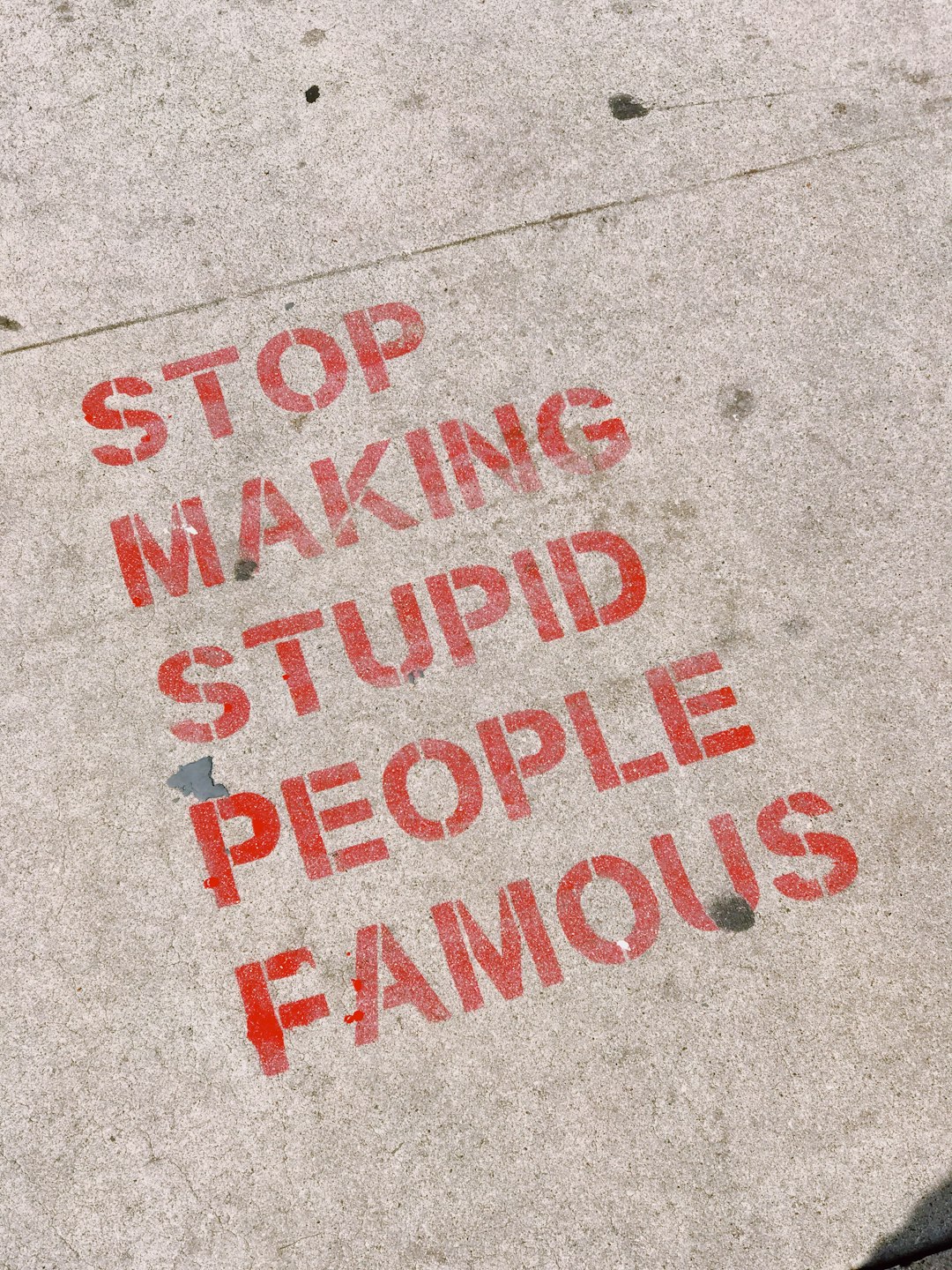

I don’t care that critical race theory was developed by academic dingbats; its claims are stupid anyway. There’s plenty in the US civil rights tradition that preceded it that’s smart and worth reading. The poor intellectual output from the likes of Bell, Richard Delgado, bell hooks, and Angela Davis should be confronted honestly, though, and the extent to which these people were given a leg-up thanks to various forms of affirmative action acknowledged.

Relatedly, the problem of the diversity hire is, shall we say, pressing. Something that started in the academy in the 1960s is now everywhere. Time was—I’m old enough to remember—when, if you encountered a woman in a senior role, she would be stellar, far more able than her male colleagues. There was an 80s joke about it: women have to be twice as good as men to get half as far, but then, that’s not difficult.

Unfortunately, this is no longer true, and not just for the banal reason that you’ll run out of talented women in a human population at about the same time you run out of talented men.

You’ve no doubt read all sorts of things on affirmative action in US universities and how it discriminates against whites and Asians (I’ve contributed a piece to the genre). I’ve no interest in relitigating that issue here. Instead, I’d ask you to turn your mind to the question a woman or minority climbing the career ladder confronts in this sort of environment.

Am I here because I can do the job, or because I tick a box?

And yes, I know there are loads of because I’m worth it types who don’t care how they get ahead, the sort of people who—in other times and places—make and accept bribes. Folk willing to do anything to get on top? They’ve always existed.

Many people, however, experience guilt or shame—and sometimes both—and do ask themselves this question. This has become so pervasive among professional women of my acquaintance I’ve caught myself giving thanks for being north of 50. 50-year-olds, it seems, are considered old enough not to have enjoyed unwarranted preferment, at least in the UK & Commonwealth (I can’t speak for the US).

In one case known to me, an ethnic minority woman in a senior role discovered she was a diversity hire—thanks to an HR idiot hitting ‘reply all’ with an email chain attached—and proceeded to have a serious psychiatric breakdown. My God, they hired me for my face was her despairing comment. She quit not long afterwards, shamed and broken.

Not only do we not help our societies when we do this—the competency crisis, especially in the US, is real—we don’t help the people to whom we do it, either. For the system to keep functioning, we have to assume that ‘disadvantaged’ people lack personal honour and won’t care if they find out the real reason their career progression has gone so well lately.

Finally, it matters that the political claims liberal democracies make—including about female political and civil society participation—are as strong and accurate as can be, especially when it comes to addressing opponents of liberal democracy.

The great rival view of the status of women—as contrasted with not only liberal democracies but also with many modern autocracies, like China and Russia—emerges from within the Islamic tradition. Women are subordinated in Islam for reasons that are wrong but carefully worked up in much the same way as Derrida, Foucault, and de Beauvoir thought their thoughts through to the end.5 The great polymaths of medieval Islam were not numpties. There’s a reason Lorenzo and I are always quoting Ibn Khaldun.

If any Muslims are to be persuaded—and no, I’m not talking about Hamas or similar, they’re obviously not persuadable—that their prophet and the tradition he inaugurated is wrong about women, then it’s fair to say that pseudoscience and conspiracism are no way to do it.

Saint Louis University Law Journal 34, no. 3 (1990): 393-406.

Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape, p. 15 (Ballantine Books, 1993).

Women Who Kill, p 25. (Feminist Press, 2009).

The Blank Slate: the Modern Denial of Human Nature, p 371 (2nd edition, Penguin Books, 2019).

I like my father’s description of flawed but skilled reasoning: ‘wrong, but in interesting ways.’

Well, this blew up & became super popular! Some of you are having your own within-thread chats already while I really do need to respond to some other people directly. Unfortunately that won't be this evening due to consulting commitments.

Promise to get my finger out in due course.

Alas modern Western feminism is not spending much time trying to influence Islam (see the relative lack of response to the Taliban or the women bravely protesting the Hijab in Iran). That kind of thing used to be a big part of discussion among campus feminists 20+ years ago. But now the focus is entirely on discrimination etc in the West, which while it exists, is nothing like living under the Mullahs. This is partly the narcissism of victimhood, partly parochial ignorance, and in a big part a reluctance to critique any situation where the misogynists are not white.