Theory as a Barrier to Understanding

Could economists (and other social scientists) try to be less blinkered by Theory?

With this essay, Lorenzo Warby & yours truly return you to your usual (wonkish) programming. The piece below follows on from this one, which forms the first part of our explanation for why economists are struggling to make themselves heard on tariffs.

We will hold a Chatham House Zoom chat for paid subscribers to discuss both pieces at some point in the next 10 days. Both pieces are, as always, free to read.

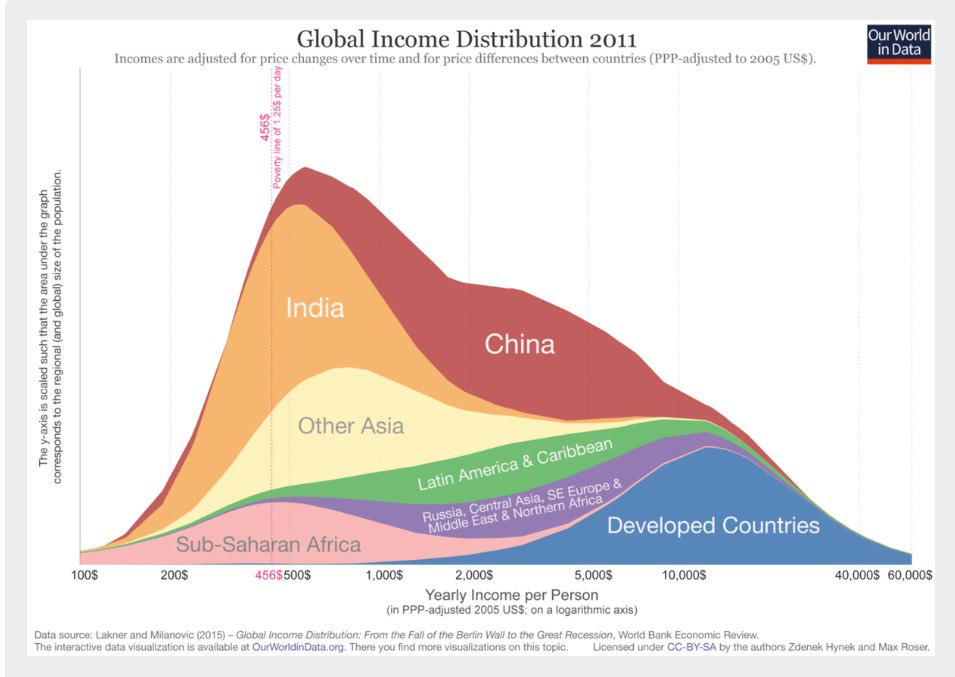

Income and wealth inequalities between countries dwarf inequalities within countries. Being in the top 50 per cent of the income of a developed democracy puts you in a much higher position when it comes to global income.

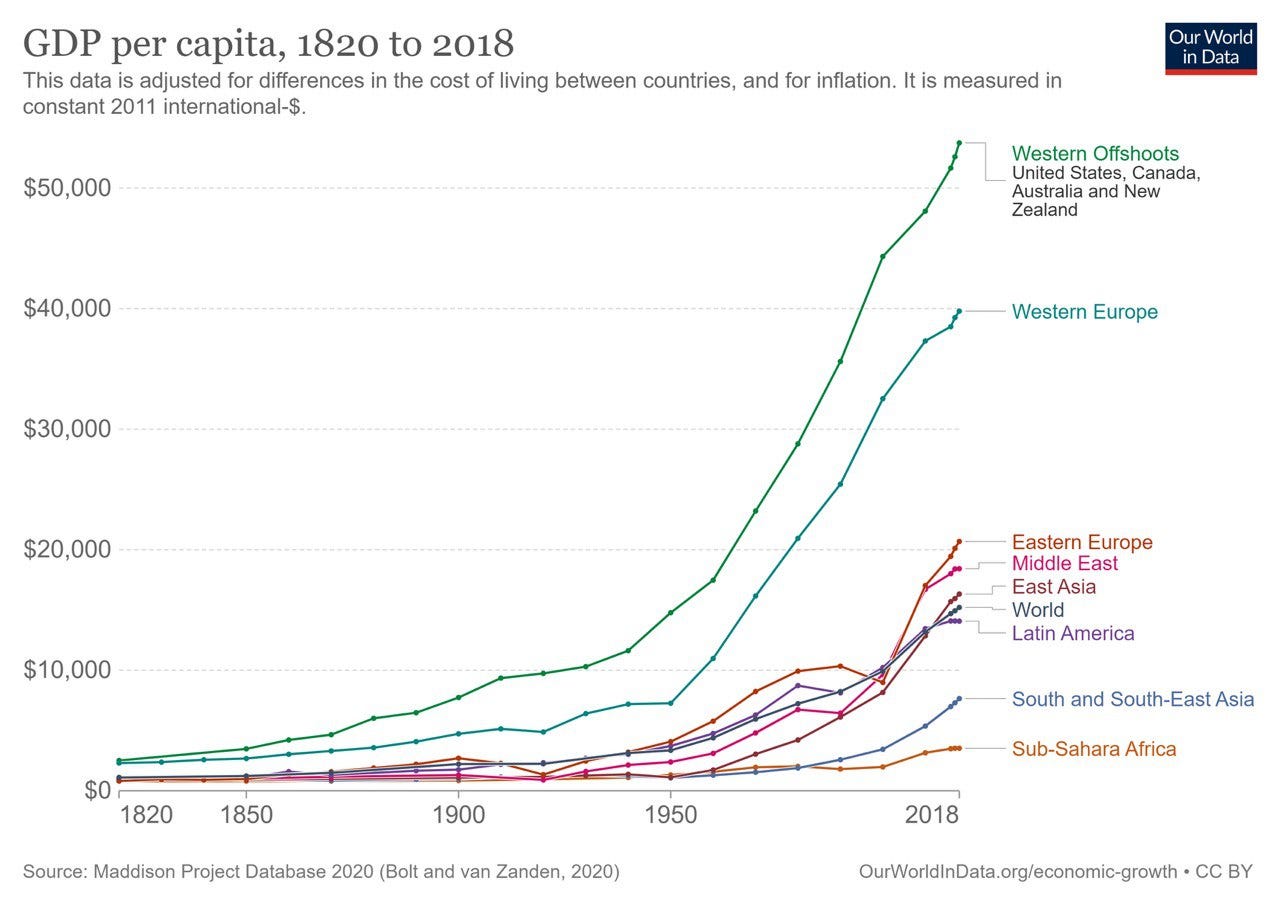

This is because productivity differences between countries dwarf productivity differences within countries. This dramatic divergence in relative productivity is a historically recent phenomenon that mostly took off after 1820—with the invention of railways and steamships—though some estimates suggest that NW Europe and parts of East Asia started drawing ahead from about 1500.

The current best evidence suggests a combination of culture and institutions explains these patterns. If it were just a matter of useable knowledge, one would expect economies to converge fairly quickly as folk copied what made people so much richer.

If you look where people were in more economically developed countries in 1500 and then note where their descendants live now, those are richer countries. It’s the culture and institutions they took with them that turns out to be crucial, not least because this facilitates invention/innovation and use of technology.

Some countries have significantly caught up with the most prosperous countries. Leaving aside cases of small populations with lots of natural resources, the successful “catch-up” countries adapted not merely useful technological and organisational—but also institutional—practices to their own circumstances. Much of this has amounted to East Asians catching up with NW Europeans and their descendant societies.

The societies that did “catch up” had states whose leaders were not only willing, but able, to adapt. That lots of countries have failed to emulate such successes suggests that there are some serious barriers to doing so. Then again, so does how historically recent such variable surges in productivity are.

The simple reality of such dramatic and persistent differences in productivity suggests people would be generally better off economically if they moved from poorer to richer countries. Which is, of course, why lots of people do and even more people express willingness to do so.

If people are more productive in wealthy countries, then wealthy countries should expect to benefit from having people move to them and thereby become more productive. In an accountancy sense, this is trivially true. The output of the migrants is added to the country’s GDP: voila!, migration is an economic boon to the receiving country.

The trickier question is what the effects are for the already resident population. The answer is: it depends. It depends on which migrants, the scale of migration, and on which residents.

If culture and institutions matter—as they clearly do—effects on residents will depend on how well the cultures that migrants bring with them adapt to local culture and institutions. It will also depend on how the scale and content of the migration flows affect the culture and institutions of the receiving country. What level of capital and skills migrants have will also make a difference.

Human societies are not built on transactions. They are built on connections first, then on transactions, then on the interaction between transactions and connections, and on expectations about both. The Loury principle—that we begin embedded in a series of social connections and expectations well before we start economically transacting—means social placement and cultural framings matter, as do institutions. As a review article on the role of culture in the happenstance of human affairs tells us:

Although using very different methodologies, the studies all provide evidence leading to the same general conclusion: individuals from different cultural backgrounds make systematically different choices even when faced with the same decision in the same environment. (Emphasis added.)

I am suspicious of attempts to separate the effect of institutions from those of culture, since it is clear institutions and organisations work differently in different cultures. As military analyst Kenneth Pollack notes:

… until relatively recently, Western economics and management theory took as a bedrock assumption that universal factors such as the availability of technology and the profit motive would produce similar organizations and methods of operation in any business regardless of cultural factors. This has been challenged broadly by new studies of the impact of cultural preferences on organizations, management, and leadership, such as the massive Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) study of such practices in 62 different countries. The GLOBE study found that societal culture had a far greater impact on leadership, management, and organizational behavior than market forces and industry effects (i.e., industry-wide practices across societies). This and other such studies have increasingly demonstrated that, despite the Darwinian competition of the marketplace (akin to the competition of combat), organizations function very differently in different societies. They have found that this holds true even for businesses nominally owned by foreign entities, which have to take on the patterns of behavior of the host country to survive and thrive. (Armies of Sand, P.408)

Economist Arnold Kling is correct: economics should be the study of human interdependence, which is why countries and communities as just-places-where-transactions-happen is such an inadequate basis for analysis.

If, for example, part of what makes a country so productive is being a high trust culture with robust convergent expectations—so transactions are much easier to engage in—then any migration that generates serious divergence in relevant expectations, lowering trust, will impose significant costs on local residents.

Patchy policy understanding

In 2001, the UK Cabinet and Home Offices issued a policy paper on migration. It was an optimistic policy paper about the benefits of migration. In the words of the paper:

If all markets are functioning well, there are no externalities, and if we are not concerned about the distributional implications, then migration is welfare-improving, not only for migrants, but (on average) for natives.

Obviously, not all markets exist, there are externalities (effects on third parties), and distributional implications matter. Various “wouldn’t it be nice” gains are cited:

• intangible social and human capital: migrants may have attributes – entrepreneurialism, for example – that generate benefits for natives

• diversity: natives may gain (tangible or intangible) benefits from interacting with migrants from different backgrounds and cultures.

What is not discussed are the possibilities for the disruption of local social capital, local connections, and convergent expectations. We are a normative species precisely because of the cooperation advantages of robust convergent expectations.

The UK policy paper does not seriously wrestle with diversity imposing cultural transaction costs, leading to loss of shared expectations. It fails to grasp that these effects are differentiated by locality. How culturally different and distant newcomers are matters.

Then we get what has become a boilerplate misdirection:

Britain is a country of immigration and of emigration

Yes, there has been a lot of emigration from Britain, especially after the development of railways and steamships in the 1820s. Nevertheless, Britain has a long history with a very stable population, with incoming groups being small as a proportion of the population.

The smaller the group relative to the resident population, and the less culturally distant they are, the easier they are to absorb and incorporate. Migration is, like most things, one of decreasing marginal benefits and increasing marginal costs.

Then we get pre-emptive presumed incapacity:

… trying to eliminate migration through immigration control policy alone is likely to be very difficult.

Various countries have proved entirely been able to do so. We get false claims of necessity:

… migration is essential to growth in some areas.

The history of c19th labour-exporting Britain shows this is nonsense. Being convenient for economic transacting is the not the same as being essential.

The issue of an ageing population is raised, citing the UN Replacement Migration Report. This alleged benefit of migration is typically exaggerated in its benefits, as migrants also age.

The 2001 paper tells us that:

The Government believes that encouraging citizenship will help to strengthen good race and community relations and that ‘one measure of the integration of immigrants into British society is the ease with which they can acquire citizenship’.

Good “race and community relations” is a moralised version of social stability, but what would encourage social instability?

Every polity is based around an institutional commons: a set of interlocking institutions in a particular territory. Like any commons, an institutional commons runs the risk of people under-investing in it and over-extracting from it. Much of what successful polities do is to encourage the reverse.

The 2001 UK policy paper implicitly recognises potential cultural transaction costs while implicitly holding the locals responsible for any problems. The subsequent discourse has typically taken migrants doing less well than the national average as a moral burden on the locals. Migrants have come to be used as a moralised social weapon against locals (especially the local working class).

This is especially so if migration is turned into—as it has been—a moral project. Bringing up costs of migration for locals has become morally illegitimate, and part of that attack has turned on the claim such concerns are economically illiterate.

There are also potential problems from migrant diversity, though it is not put like that in the 2001 paper:

… migrant experiences are more polarised than those for the population as a whole, with larger concentrations at the extremes.

So, migrants can be expected to have a polarising economic effect on the wider society. As the paper says:

Migrants have mixed success in the labour market: some migrants are very successful, but others are unemployed or inactive.

Which suggests careful selection of migrants might be a good idea. There is also a touch of UK triumphalism that has not worn well:

Migrants appear to perform well in the UK labour market compared to other EU countries (although cross-country comparisons need to be treated with care, given data problems). The migrant population in the UK has an unemployment rate of six per cent compared with an unemployment rate of just under five per cent for the UK born. In France, non-EU migrants face a 31.4 per cent unemployment rate, compared to 11.1% for the French. Nearly half of migrants under the age of 26 are unemployed, twice the rate of French nationals in the same age group.Similarly, migrants are twice as likely to be unemployed as natives in Denmark, three times as likely in Finland, and four times as likely in The Netherlands.

This point goes both ways: that attention should be paid to both UK policies and institutions—what sustains them, what undermines them—and how migrants are selected. Systematically blocking voters from having their preferences on migration policy matter is obviously socially and politically corrosive.

Then there is a classic “the devil is in the details” problem:

Overall, migrants have little aggregate effect on native wages or employment, though they can have more of an effect (positive and negative) on different sub-groups of natives.

Another passage that has not worn well:

Migrants’ impacts on congestion and other externalities, like impacts on housing markets, can be both positive and negative, but not enough is known about them.

Unemployment is indeed far more of a structural than a labour-force size problem:

It is perhaps not surprising that immigration has no measurable impact on unemployment in the US and UK. The “ lump of labour” fallacy – that there are only a fixed number of jobs to go round – has been thoroughly discredited, and it is increasingly recognised that, given sound macroeconomic management, unemployment is primarily a structural phenomenon.

As the paper notes, migration affects the composition of output.

There are, however, a series of both highly supply-constrained and non-market factors that operate as constraints and so affect the consequences—including the distributional consequences—of migration. For instance, effects on rents and house prices are not seriously addressed:

many of these [congestion, housing] pressures reflect the fact that existing infrastructures are unable to adapt quickly enough to large changes in a local population.

There is an entire literature on how internal and external migration encouraged forms of local zoning that block housing provision—what has since become known as NIMBY (Not In My Backyard). California took that to levels sarcastically known as BANANA (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anyone).

The protection of various forms of local amenity becomes more salient as population pressures on localities rise. Of course external migration—bringing in non-voting residents—encourages NIMBYism that restricts housing supply and drives up house prices and rents: this has often been much of the point of such restrictions.

Another passage that has not aged well:

The broader fiscal impact of migration is likely to be positive, because of migrants’ favourable age distribution (a greater proportion of migrants are of working age), and the fact that migrants in work have higher average wages than natives …

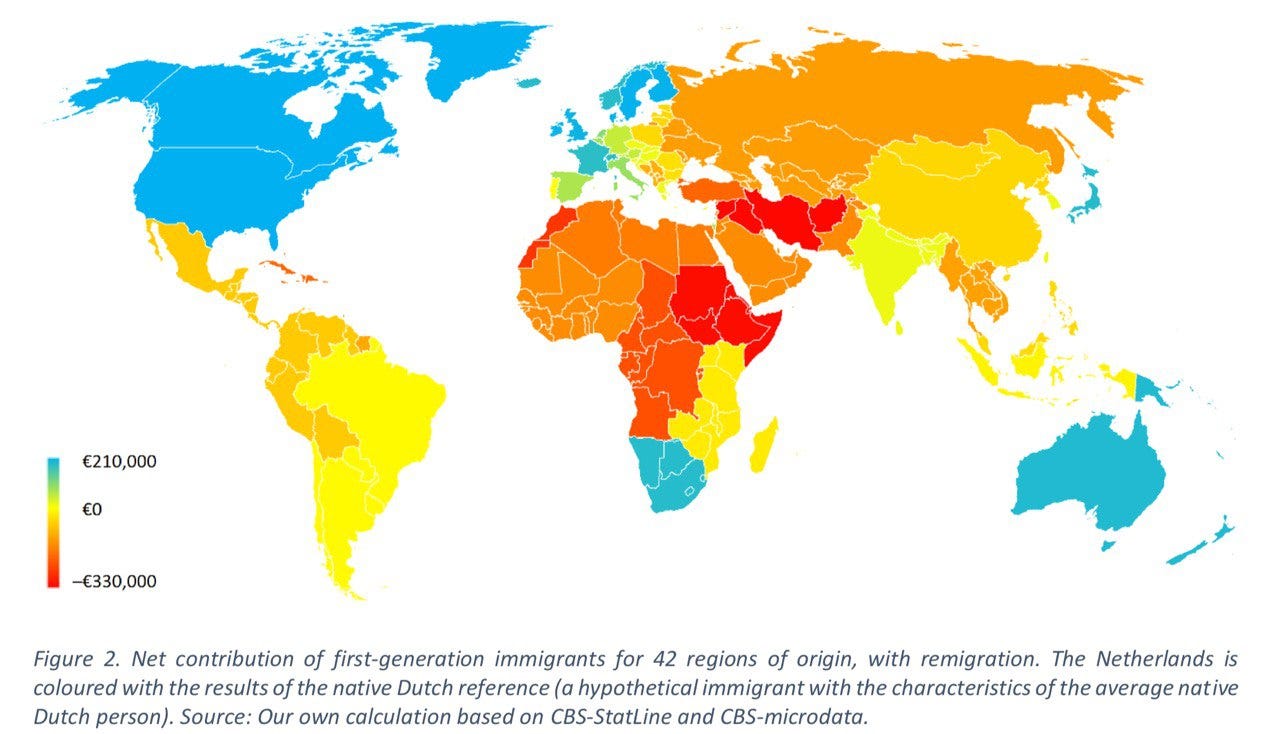

Fiscal effects have not been positive for many migrants and the amelioration of ageing effects is marginal. As a recent Dutch study found:

Only 20% of all immigrants [to the Netherlands] make a positive lifetime net contribution to the public budget. Groups with large contributions come from Scandinavia, the Anglo-Saxon world and a few other countries like France and Japan.

The expectation of positive fiscal effects was taken to be a general feature of migration in the 2001 UK policy paper, despite repeatedly noting that migrants were heterogeneous and tending towards economic extremes.

Then we get a classic careful caveat:

Not enough is known about migrants’ social outcomes.

Such social outcomes include problems of organised sexual predation. Though, to be fair, they were social outcomes for non-migrants—just rather serious ones.

The above is a government policy paper, with the caution and caveats one expects from such documents. There are, however, problems with the paper due to blindspots and some key expectations not having been borne out.

A simple solution

If people are so much more productive in wealthy countries, then the more people move to wealthy countries, the greater the gain in global wealth and income. So, this logic goes, open borders should generate an enormous global gain in wealth and income.

A 2011 paper by economist Michael A. Clemens attempts to quantify this and (allegedly) think through the scale and whys of such gains. As he says, however:

These estimates are sensitive to assumptions, and in the following sections I discuss the (limited) available research on four kinds of assumptions that underlie these estimates: how migrants affect nonmigrants, the shape of labor demand, the effect of location on productivity, and the feasibility of greater migration flows.

There are lots of considerations that someone with some sense of historical practicalities would point to that are not covered. For example, how resilient are institutional orders to dramatic changes in their resident population? But to concern oneself with resilience, one has to (1) not see efficiency as the be-all and end-all policy or welfare considerations; (2) see polities and communities as something more than just places-where-transactions-take-place, and (3) see people as varying along a range of relevant dimensions.

Treating efficiency concerns as dominant—and polities and communities as primarily places where transactions happen, and happen in much the same way—means we get some truly dramatic estimates of the gains from global free flows of labour:

The gains from eliminating migration barriers dwarf—by an order of a magnitude or two—the gains from eliminating other types of barriers. For the elimination of trade policy barriers and capital flow barriers, the estimated gains amount to less than a few percent of world GDP. For labor mobility barriers, the estimated gains are often in the range of 50–150 percent of world GDP.

There are two possibilities: (1) economists are such clever people that they have noticed something huge everyone else has missed; or (2) they are ignoring some crucial factors.

In fact, existing estimates suggest that even small reductions in the barriers to labor mobility bring enormous gains. In the studies of Table 1, the gains from complete elimination of migration barriers are only realized with epic movements of people—at least half the population of poor countries would need to move to rich countries.

This is such an utter fantasy that only folk lost in Theory would regard it as a benchmark for anything. Even in terms of simple economics, what about diminishing marginal benefits and increasing marginal costs? Or is the claim that migration comes with so many positive economies of scale—and no relevant constraints—that we need not consider this? (It doesn’t.)

A conservative reading of the evidence in Table 2, which provides an overview of efficiency gains from partial elimination of barriers to labor mobility, suggests that the emigration of less than 5 percent of the population of poor regions would bring global gains exceeding the gains from total elimination of all policy barriers to merchandise trade and all barriers to capital flows. For comparison, currently about 200 million people—3 percent of the world—live outside their countries of birth (United Nations, 2009).

This requires resident citizens to agree to be swamped in their own countries. This is classic obsession with efficiency and gains from trade with no consideration of institutional resilience, interactions, or connections.

The notion that institutions are infinitely resilient in response to any rate of population increase and cultural change is deeply, deeply stupid. Any implied notion—from not grappling with this issue seriously—that either institutions or culture don’t matter is even more so.

People become mathematically convenient economic “particles” with no awkward ongoing connections, normative or other differentiation:

For nonmigrants, the outcome of such a wave of migration would have complicated effects: presumably, average wages would rise in the poor region and fall in the rich region, while returns to capital rise in the rich region and fall in the poor region. The net effect of these other changes could theoretically be negative, zero, or positive. But when combining these factors with the gains to migrants, we might plausibly imagine overall gains of 20–60 percent of global GDP. This accords with the gasp-inducing numbers in Tables 1 and 2.

We see here the Olympian Economist, sure that Theory directs them to all the relevant significant factors.

… we should expect to see proportionately greater international price wedges between different labor markets than between different goods and capital markets. … In Clemens, Montenegro, and Pritchett (2008), we document gaps in real earnings for observably identical, low-skill workers exceeding 1,000 percent between the United States and countries like Haiti, Nigeria, and Egypt. Our analysis suggests that no plausible degree of unobservable differences between those who migrate and those who do not migrate comes close to explaining wage gaps that large.

Is that because folk are blocked from moving, or because culture and institutions vary greatly? Why are folk not simply copying what rich countries do where they already are? Obviously, because some mixture of cultural and institutional factors is in the way. How do we know they will not take at least some of those blocks with them?

Do we see persistent differences in economic outcomes between groups within the same polities? If we look at who was relatively rich in 1500 and who is rich now, is it place or people that count? The answers are, of course, yes and people.

Differences among the models’ conclusions hinge critically on how the effects of skilled emigration are accounted for; the specification and parameters of the production function (and thus the elasticities of supply and demand for labor); assumptions on international differences in the inherent productivity of labor and in total factor productivity; and the feasible magnitude of labor mobility. Assumptions on the mobility of other factors matter a great deal as well; in KV [model] the majority of global efficiency gains from labor mobility require mobile capital to “chase” labor.

Thinking that these are all the key factors is Theory-drunk nonsense. The following is bizarrely inadequate as a list of relevant considerations:

To understand what underlies these various estimates of the gains from greater labor mobility, we need better information about at least four features of these models: 1) What are the external effects of (especially skilled) emigrants’ departure on the productivity of non-emigrants? Many of the above estimates rest on the assumption that this effect is small or nil. 2) What is the elasticity of labor demand, in the origin and destination countries? Are these studies getting it about right? 3) How much of international differences in productivity depend on workers’ inherent traits—accompanying them when they move—and how much depends on their surroundings? Is productivity mostly about who you are, or where you are? 4) Finally, given the many barriers that prevent emigration today, what future level of emigration is feasible?

… economists need much more evidence than we have, but that the existing evidence gives us little reason to believe that the numbers in Tables 1 and 2 greatly overstate the gains to lowering migration barriers.

Only if you regard yourself as a master of Olympian Theory and have identified all the key factors, especially what counts as evidence. Clemens does make some good points:

…it is possible that the depletion of human capital stock via emigration inflicts negative externalities on nonmigrants. However, these externalities have proven difficult to observe, their theoretical basis remains unclear, and their use to justify policy remains shaky.

Raising the expected value of human capital can, as Clemens points out, be expected to increase investment in it. His critique of the “brain drain” literature is worth reading. Though one can reasonably wonder if emigration systematically bleeding off those with greater initiative, and independence of thought and action, is a good thing for a culture.

On the other hand:

The arrival of migrants could, for example, decrease the availability of unpriced public goods at the destination like open space, clean air, publicly-funded amenities, and a degree of cultural homogeneity that may be valued by nonmigrants.

This is a distributional effect that Clemens critiques by saying migration grows an economy: which it clearly does, if only because migrants’ economic transactions are added to the economy. This does not answer the question whether various non-migrants are made worse off. Nor does it answer what stresses might be put on the existing institutional and cultural order.

There is a persistent tendency for upper middle class Westerners—particularly Americans—to ignore distributional questions they find inconvenient. Yet distributional questions are often central to why different folk have the reactions they do. That is part of the much more general “people unlike me” problem that plagues commentary in general and the social sciences in particular.

Clemens then moves to what has become a classic mechanism for ignoring locality-based social capital, a persistent “people unlike me” problem:

If people’s taste for cultural homogeneity …

Such dismissal of social capital and social resilience has been a recurring element within the migration literature in economics. No, communities and polities are not just places where transactions happen and happen in a homogeneous way. A web of connections and shared expectations makes lots of aspects of life—including economic aspects—more functional for people. Atomised communities are dysfunctional communities.

Non-kin cooperation is Homo sapiens super-ability, which does not mean localities-as-just-places-transactions-happen. Turning connections that matter into a “taste for cultural homogeneity” is patronising, Olympian arrogance. A mixture of the “people unlike me” problem and the “people as undifferentiated economic particles” problem.

Cheap consumption is not a be-all and end-all in itself. Folk need to have the incomes so as to consume. Their communities have to be functional to avoid social pathologies. Human interdependence is a thing. Communities and countries can be homes as well as individual dwellings.

The migration literature regularly finds minimal downward effects on local wages in destination countries from increased labour supply from migration. Yet Clemens cites literature that finds more substantial upward effects on wages of source countries via increased labour scarcity. There is some tension between these two findings.

Importing low-skill workers not only depresses the return to labour by reducing its scarcity vis-a-vis capital. It also depresses the Baumol effect, where labour competition distributes the benefits of increases in productivity across the labour force. Import a lot of low-skill workers and said benefits are distributed among more workers, suppressing the wages of residents from rising to what they otherwise would be.

So, it’s not merely whether wages of non-migrants are cut from mass migration, for which the evidence is indeed thin. It is also whether wages are suppressed, for which there is much more evidence—for instance, the way low-end wages rose in the US and UK, with their considerable low-skill/low-capital migration, during the Covid migration pause but did not in Australia, whose high-skill/high-capital migration had not been suppressing the Baumol effect.

Like so many mainstream economists, Clemens pays little or no attention to questions of resilience—to the ability to adjust to changes in circumstance (supply chains anyone?)—focusing overwhelmingly on efficiency:

Existing estimates of the efficiency gains from greater emigration hinge on a critical assumption: How productive will migrants be at the destination? Many have low productivity where they now are, in poor countries. How much of that low productivity moves with them?

…whether international differences in productivity are explained by differences in people or differences in places.

…finds that most of the productivity gap between rich and poor countries is accounted for by place-specific total factor productivity, not by productivity differences inherent to workers.

Place-specific how? Place-specific due to culture and institutions. Both of these things are deeply affected by people and, for example, convergence in bedrock norms and expectations which, because of cultural (including religious) differences cannot be guaranteed.

One reason why religious, or quasi-religious, disputes can be so bitter is religious notions of the sacred create realms of action where trade-offs are not accepted. This can generate increased resilience for a community, by creating robustly grounded common expectations, schemas (patterns of belief) and scripts (patterns of action). It can also generate intense—and persistent—tensions and disputes.

The Western world (painfully) evolved mechanisms for keeping religious disputes in bounds, only for the rise of political religions—with their own notions of unimpeachable (i.e. divine) authority and no-trade-off (i.e. sacred) realms of action—to kill millions. Religion rests on evolved mechanisms that are independent of any supernatural metaphysical claims. It can be—and has been—repurposed.

Islam—particularly Greater Middle Eastern (Morocco to Pakistan) Islam—has (at best) much weaker mechanisms for keeping religious disputes in check. Post-Enlightenment Progressivism aka Critical Constructivism aka “wokery” makes alleged oppressed or marginalised groups—or at least claims on their behalf—sacred, with all the attendant epistemic closure that goes with that. By declaring migrants—and particularly Muslims—a sacred group, they have systematically sabotaged public discourse, and public policy, on migration. Their stupidity-of-arrogance (Critical) Theory has interacted quite perversely with the Olympian arrogance of (inadequate) economic Theory.

The Olympian Economist attitude keeps turning up in Clemens (2011):

…finds that it is the wealthier, better-educated, and less-nationalist individuals in rich destination countries who have more favorable attitudes toward immigration.

Yes, because those with more capital—and whose social capital is less based on location—experience more of the gains from migration and far less of the costs. This difference is not a sign of moral and cognitive failure, it is a sign of different vulnerabilities and experiences. We are back to the “people unlike me” problem and the belittling of distributional effects.

Because Clemens is concerned with the potential global effects of mass migration, he also discusses the economics of emigration rather than concentrating—as a lot of the literature does—on effects of immigration.

Remittances have become a major result of migration. Such payments to family back home have become one of the larger forms of international financial flows. The benefits of remittances are likely to be much more unambiguously positive than foreign aid, which has no overall correlation with economic growth at all. Given the intentions and scale of foreign aid, this is a stunning level of failure.

Remittances also increase the chances of migration being a net cost to workers in migration-receiving countries, as it reduces how much migrants will generate increased demand for local goods and services in migrant-destination countries. Downward pressure on wages from increased labour supply by migrants will be less compensated for by any upward labour demand effect from migrant spending on local goods and services.

When it comes to potential costs of migration, does triggering at least three civil wars (in the US, Lebanon and Jordan) and an ongoing series of wars (the Arab-Israeli conflicts) count? Does mass sexual predation count—from practitioners of a religion that has, for its entire history, sanctified sex with captives and regards its rules, those of the Sovereign of the Universe discovered by fiqh—as applying to everyone, not just believers? Does degrading the access to various localities for women and gay folk count? Does importing people who have been marrying their cousins for generations, so have elevated rates of birth defects and general sickliness, count?

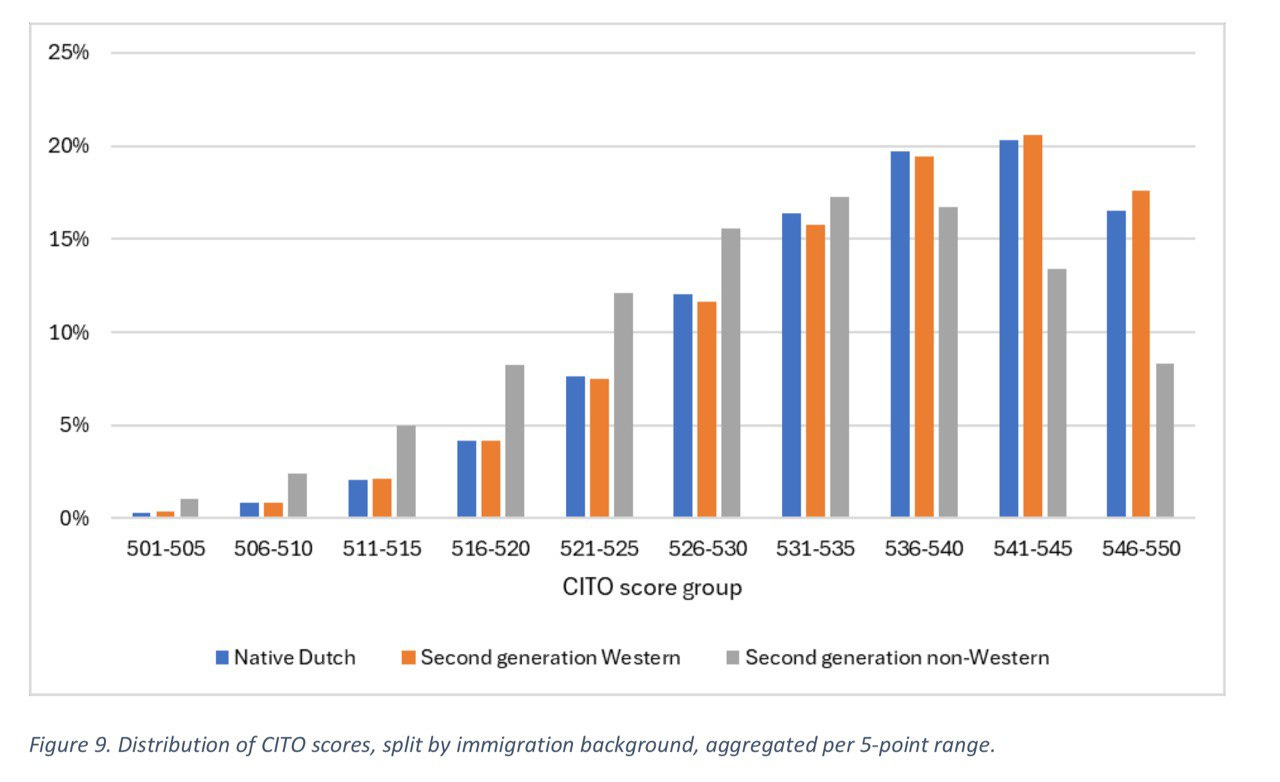

People really are not interchangeable widgets And yes, it is entirely possible that particular migrants may bring some anti-productivity, and anti-integration, cultural traits with them. As a study of the effects of different types of migrants on the Dutch Treasury found:

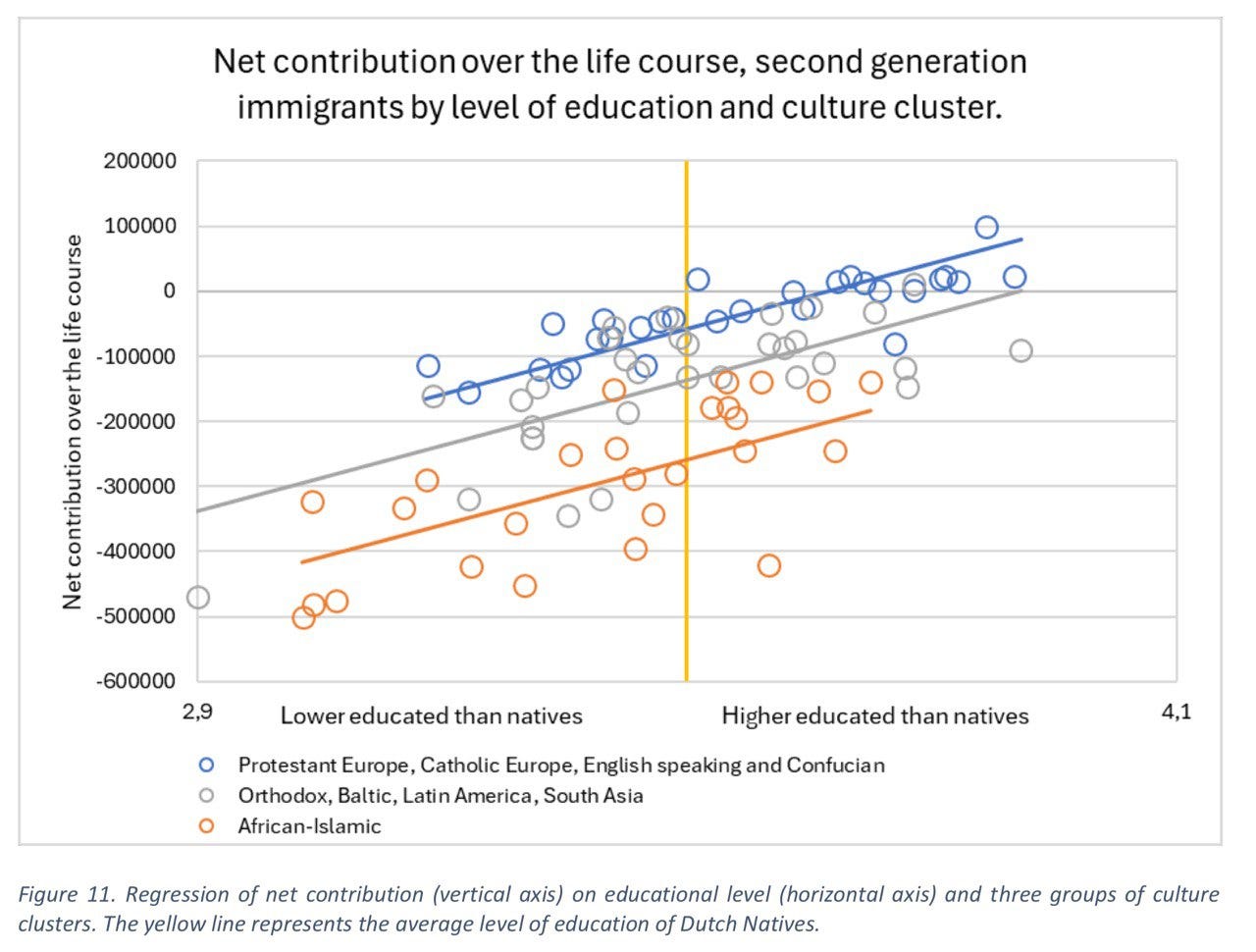

The educational level of immigrants is very decisive for their net contribution to the Dutch treasury, and the same applies to their children’s CITO scores (scores on a 50-point scale for assessing pupils in primary education). If the parents make a positive net contribution, the second generation is usually comparable to the native Dutch population. If the parents make a strongly negative net contribution, the second generation usually lags behind considerably as well. Therefore, the adage ‘it will all work out with the second generation’ does not hold true. High fiscal costs of immigrants are not that much caused by high absorption of government expenditures but rather by low contributions to taxes and social security premiums. We also find evidence for a strong relationship of average net contributions by country with cultural distance, even after controlling for average education and the cito-distribution-effect. The cultural distance to African-Islamic countries is large, and their emigrants bring large net fiscal cost, the distance to Confucian countries is modest and their emigrants on average bring the largest net benefits.

Then there is the entire question of why countries have borders and the long tradition of states worrying about integrating residents. There is a long history of states having strong integrating, or even culturally homogenising, policies. Why has nationalism had a corrosive effect on empires? What makes a polity functional or not and at what level? Why do economic outcomes vary so much between states and groups?

Treating states (and communities) as just places where transactions happen, and happen in a homogeneous way, is ridiculous. It is deeply, deeply stupid.

We see in Clemens’ paper, and in the current “open borders yay!” literature, the classic Olympian error—even apart from the people unlike me problem—of taking the continuing functioning, and its functioning at at least the current level, of the existing polity, or polities, for granted. There is no good reason to do so, and many reasons not to.

A theory of migration that is not built on a sound analysis of why states vary so much in their economic performance is nonsense. Without such an analysis, you simply cannot tell what the full effects of migration will be. Especially migration at the scale Clemens and the open border folk suggest.

Economist Bryan Caplan is the most prominent enthusiast for open borders. Garret Jones wrote a 2019 paper where he basically says “Bryan Caplan is using my model in a simple way that I wouldn’t, but if we run with that it does not lead where he says”. The analysis in the paper:

…sticks close to the theory that differences in productivity across countries are mostly externalities.

Which (1) has to be true for migration in general, and open borders in particular, to generate increased production, otherwise folk could just be as productive by remaining where they are, and (2) fits the facts. Productivity comes from transacting with others in particular cultural and institutional milieus, neither of which individual transactors have much effect on (but a critical mass of them can).

Cultures and institutions both evolve. The implication of the evidence is that they matter, a lot:

There are good reasons to doubt whether in fact permanent, unalterable elements of national productivity add up to a large number: Easterly and Levine (2003), for instance, in an influential paper, find that the historical correlation between good geography and good modern outcomes can be explained entirely by good modern institutions: in the past, good places predicted good policies. Will that correlation hold in the future? Only a structural model of institutional quality can answer that question, and such a model is beyond the scope of this paper. In any case, let's recall a critical fact: permanent productivity shocks attached to a precise location, whether explained or unexplained, are indispensable to the case for Open Borders.

There is no such thing as Magic Dirt. The only way one can mount an “all it takes is for people to move where productivity is higher”—without a robust theory of how and why polities vary so widely in productivity—is by making location Magical. Or, to put it in more theoretical language, there are “permanent productivity shocks attached to a precise location”.

One response is “those places have better public policies”. Well, yes, obviously. A much cited 1995 paper by economists Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner shows the systematic difference policy makes for economic growth—specifically, trade openness and reasonably stable protection of property rights.

But why do countries vary so much in their policy choices? Good public policy is a form of useable knowledge. If that was all there was to the matter, why doesn’t everyone converge towards high productivity? What if ideas don’t travel?

Moreover, let us just ponder the scale of movements required to generate the alleged global wealth gains from open borders. In any system with constraints, unless there are economies of scope or scale, there will be declining marginal benefits and increasing marginal costs.

So, to assess the potential gains, one has to assess the various constraints. Which requires, guess what, a robust analysis of why polities vary so much in productivity and—a point often missed—why groups within polities vary. It must also cover why good policy is not just readily-transferred useable knowledge.

Consider the fact that there are three factors of production—land, labour, and capital. (Some folk add entrepreneurship, but I prefer to see that as a coordinating function rather than a factor of production.)

So, what happens if you crowd a whole lot more people into a given area of land? Congestion costs and rents are going to go up. Potentially, a lot. That is going to very much generate declining marginal benefits and increasing marginal costs for migration.

This we can absolutely see happening. Who is it going to affect most adversely? The local providers of labour.

One hint that scale (and so feedback) really, really matters, is that the richest countries per capita tend to be small countries. The major exception is the US, which is a highly federal state. Turning the European Economic Community into the European Union has been a negative for European economic growth.

Feedback effects matter. We are creating societies of broken feedbacks, not least by use of a pervasive arrogance of Theory to delegitimise concerns and experiences. The arrogance of both Marxist and Nazi Theory oppressed and blighted the lives of hundreds of millions and killed tens of millions.

More recently, the arrogance of Critical Theory—derivatives of Marxism that update its oppressor/oppressed template—has corrupted education, from schooling to universities. The arrogance of Queer Theory has seen the hormonal and surgical mutilation and sterilisation of minors passed off as “care” along with the Lysenkoist corruption of scientific research, publication, and professional associations. The arrogance of Settler-Colonial Theory has turned brutal, murderous Jew-hatred into “resistance”.

The use of overblown Theory by the activist professional-managerial class to insert itself into as many resource-flow as possible—with as much control over discourse as possible—degrades both discourse and democracy. This has been especially true with migration, as it is so useful for favour-divide-and-dominate games (aka identity politics), fracturing the demos, right down to local communities and local accountability.

The recent sentencing guidelines in the UK—which defy both overwhelming public opinion and centuries of legal thought in both common and civilian legal systems—are an emblematic example of the arrogance of Theory operating in captured institutions: including variable outcomes between groups being turned into a moral burden for the locals.

Any notion that the only issue of consent is for incoming migrants is a moral and political nonsense. Unfortunately, the “migration is a big economic positive” literature—however grotesquely inadequate it is—has done its bit to de-legitimise working-class concerns, thereby adding to the costs of migration by degrading democratic feedback and public discourse.

Bryan Caplan, in his response to Garret Jones writes:

So even though open borders nearly doubles the production of mankind, it reduces living standards of the current inhabitants of rich countries by a massive 40%. In short, we have a classic NIMBY (“Not In My Backyard”) picture; open borders is great for humanity, but nevertheless awful for us.

It is hard to know where to start with this piece of Olympian arrogance parading as care. First, this is a policy that will never achieve democratic consent. Any version of this can only proceed by lying or otherwise functionally disenfranchising working-class votes. We can observe efforts to do precisely this, especially in the EU and UK. Sabotaging democratic accountability has repeatedly proven to be bad for human flourishing.

Second, it is a classic example of utilitarianism not scaling down to the individual or even the national level. Human morality simply does not work like that, nor should it be expected to do so. Thirdly, it really is “polities (and local communities) are just places for transactions to homogeneously happen” reasoning.

For that is another aspect of migration: it has the potential to shift political power radically. This is precisely how mass migration has fractured polities along their fault lines, triggering civil wars and civil strife.

The notion that folk can never bring dysfunctions with them is patent nonsense. The notion that they cannot reduce the functionality of the polity they are entering is also patent nonsense.

The notions that there are no problems of culture, of trust; that institutions cannot become stressed or broken; that the operation of institutions are independent of norms, expectations, cultural schemas (patterns of belief) and scripts (patterns of action), of the life strategies, of the people operating them, is all also patent nonsense.

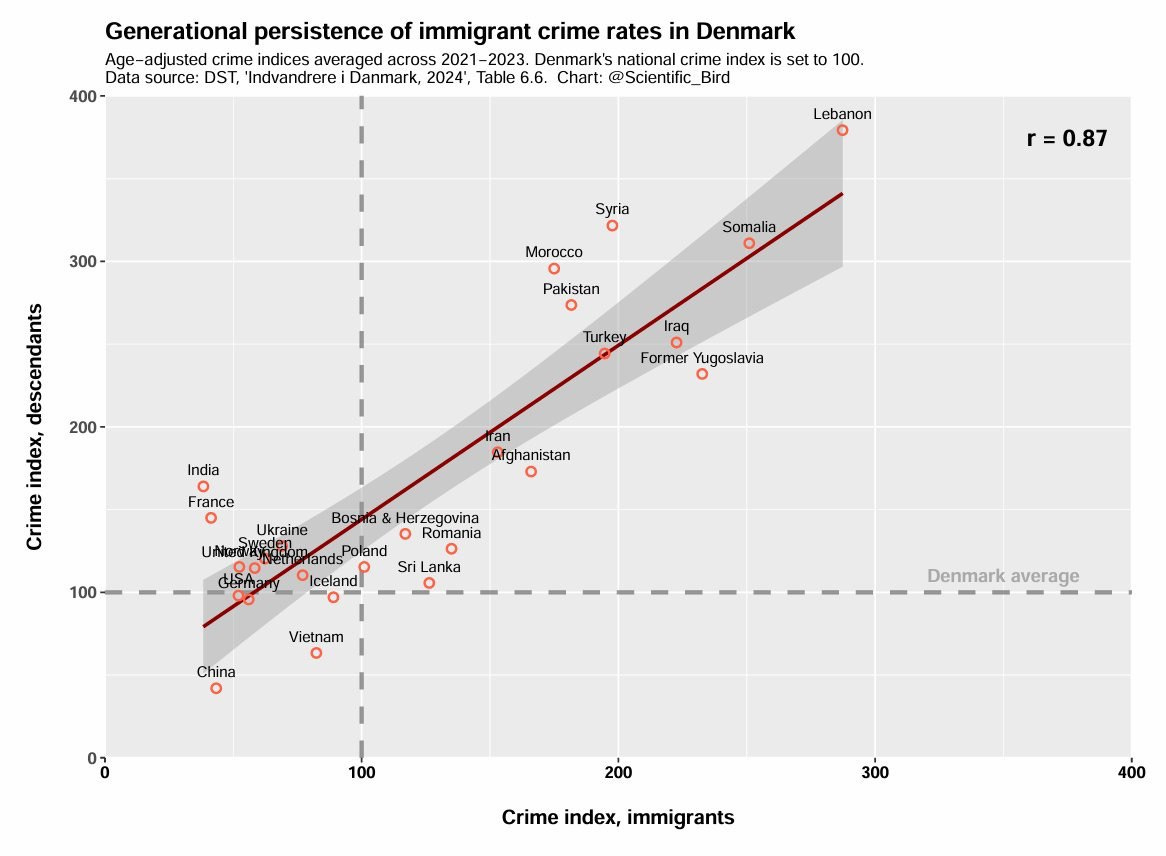

If, for example, you import significant numbers of people with not only higher crime rates, but intergenerationally higher crime rates, you reduce the trust level in a society. Unfortunately, as the predictors of crime have a high degree of heritability, both genetically—such as executive functions and personality traits—and culturally—such as honour cultures—intergenerational persistence in elevated crime rates is to be both expected and observed.

If you then make any negative differences in outcomes between groups a moral burden on the locals—while turning migrants into a sacred group—then utterly perverse policy outcomes are more or less guaranteed. This can be made worse again by making degrading the heritage of the locals into an ongoing moral project.

So there is a multi-level attack on folk’s sense of home: at a community, national, and cultural level. Then, with the right level of epistemic closure, one can get utterly outraged that all this—including wildly uneven benefits and costs of migration—generates political responses.

Devaluing the institutional commons

A polity is based around an institutional commons, an interlocking set of institutions and convergent expectations. Creating and maintaining an effective and resilient institutional commons cannot remotely taken for granted. Hence the effort polities have put in to doing so and how polities can come apart when that fails.

What do we see in South Africa? A country heading towards collapse through the systematic debauching of its institutional commons.

Most of the wars since 1945 have been civil wars. Most of the genocides have been internal genocides. Even the most obvious counter-example—the Holocaust—took place in a zone of destroyed states and significantly recruited local collaborators. Countries that have more recently have achieved internal peace typically had preceding histories of internal violence.

The lack of a robust theory of why productivity varies so dramatically between countries—despite clear evidence about good and bad policies—is not an unfortunate absence in migration theory. It is an absolutely disabling absence. It is why economists have got migration so seriously wrong. Polities and communities are not just places where transactions homogeneously happen.

The Samuelsonian presumption that economists are dealing with economic “particles” who can be mathematised via a social physics continues to do a lot of damage. It is the Lockean “blank slate” wreaking analytical havoc. The failure of economists on migration has been so catastrophically bad that it runs the risk of de-legitimising their entire discipline.

References

M. Ajaz, N. Ali, G. Randhawa, ‘UK Pakistani views on the adverse health risks associated with consanguineous marriages,’ Journal of Community Genetics, 2015;6(4):331-342. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4567984/

Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano, ‘Culture and Institutions,’ Journal of Economic Literature, 2015, 53(4), 898–944. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.53.4.898

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Prey: Immigration, Islam, and the Erosion of Women’s Rights, HarperCollins, 2021.

Scott Atran, Robert Axelrod, Richard Davis, ‘Sacred Barriers to Conflict Resolution,’ Science, Vol. 317, 24 August 2007, 1039-1040. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1144241

Jan van den Beek, Hans Roodenburg, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, ‘Borderless Welfare State - The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances,’ 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371951423_Borderless_Welfare_State_-_The_Consequences_of_Immigration_for_Public_Finances

Jan van de Beek, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, Hans Roodenburg, The Long-Term Fiscal Impact of Immigrants in the Netherlands, Differentiated by Motive, Source Region and Generation, IZA DP No. 17569, December 2024. https://docs.iza.org/dp17569

Abdulbari Bener, Ramzi R. Mohammad, ‘Global distribution of consanguinity and their impact on complex diseases: Genetic disorders from an endogamous population,’ The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 18 (2017) 315–320. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110863017300174

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

George Borjas, ‘Immigration and the American Worker: A Review of the Academic Literature,’ Center for Immigration Studies, April 2013. https://cis.org/Report/Immigration-and-American-Worker

Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith, Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Migration, First Second, 2019.

David Card, Christian Dustmann and Ian Preston, ‘Immigration, Wages, and Compositional Amenities,’ Norface Migration Discussion Paper No. 2012-13, February 2012. https://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/immigration-wages-compositional-amenities.pdf

Joshua Charap and Christian Harm, ‘Institutionalized Corruption and the Kleptocratic State,’ IMF Working Paper, WP/99/91, July 1991. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/Institutionalized-Corruption-and-the-Kleptocratic-State-3152

Michael A. Clemens, ‘Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 25, Number 3, Summer 2011, 83–106. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.25.3.83

European Commission, Projecting The Net Fiscal Impact Of Immigration In The EU, EU Science Hub, 2020. https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/projecting-net-fiscal-impact-immigration-eu_en

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018.

Manuel Eisner, ‘Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime’, Crime and Justice; A Review of Research, 2003. 30, 83-142. https://www.vrc.crim.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/manuel-eisner-historical-trends-in-violence.pdf

Laura E. Engelhardt, Daniel A. Briley, Frank D. Mann, K. Paige Harden Tucker-Drob, ‘Genes Unite Executive Functions in Childhood,’ Psychological Science, 2015 August, 26(8), 1151–1163. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4530525/

T. Epper, E. Fehr, K.B. Hvidberg, C.T. Kreiner, S. Leth-Petersen, & G. Nytoft Rasmussen, ‘Preferences predict who commits crime among young men,’ Proceedings National Academy of Sciences U.S.A, 119 (6) e2112645119. https://www.pnas.org/doi/epub/10.1073/pnas.2112645119

Mohd Fareed and Mohammad Afzal, ‘Genetics of consanguinity and inbreeding in health and disease,’ Annals Of Human Biology, 2017 Vol. 44, No. 2, 99–107. https://www.academia.edu/33934871/Genetics_of_consanguinity_and_inbreeding_in_health_and_disease

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989] 1994.

Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´inez-Toledana, Thomas Piketty, ‘Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages In 21 Western Democracies, 1948–2020,’ The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol. 137, 2022, Issue 1, 1-48. http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/GMP2022QJE.pdf

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Ryan James Girdusky and Harlan Hill, They’re Not Listening: How the Elites Created the National Populist Revolution, Bombardier Books, 2020.

Edward L. Glaeser and Andrei Shleifer, ‘The Curley Effect: The Economics of Shaping the Electorate,’ The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, Vol. 21, No. 1, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/curley_effect.pdf

Stephen Glover, Ceri Gott, Anaïs Loizillon, Jonathan Portes, Richard Price, Sarah Spencer, Vasanthi Srinivasan, and Carole Willis, Migration: an economic and social analysis, Home Office Economics and Resource Analysis Unit and the Cabinet Office Performance and Innovation Unit, January 2001. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75900/1/MPRA_paper_75900.pdf

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

Mark S. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties,’ American Journal of Sociology, Vol.78, No.6, (May 1973), 1360-1380. https://snap.stanford.edu/class/cs224w-readings/granovetter73weakties.pdf

Mark S. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233. https://www.csc2.ncsu.edu/faculty/mpsingh/local/Social/f15/wrap/readings/Granovetter-revisited.pdf

M.F. Hansen, M.L. Schultz-Nielsen,& T. Tranæs, ‘The fiscal impact of immigration to welfare states of the Scandinavian type,’ Journal of Population Economics, 30, 925–952 (2017), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-017-0636-1

Ella Hill, ‘As a Rotherham grooming gang survivor, I want people to know about the religious extremism which inspired my abusers,’ Independent, Sunday 18 March 2018. https://https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/rotherham-grooming-gang-sexual-abuse-muslim-islamist-racism-white-girls-religious-extremism-terrorism-a8261831.html

Garett Jones, ‘Measuring the Sacrifice of Open Borders,’ George Mason University, November 2019. http://digamoo.free.fr/garettjones2019.pdf

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Stephen Leslie, Bruce Winney, Garrett Hellenthal, Dan Davison, Abdelhamid Boumertit, Tammy Day, Katarzyna Hutnik, Ellen C Royrvik, Barry Cunliffe, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium, Daniel J Lawson, Daniel Falush, Colin Freeman, Matti Pirinen, Simon Myers, Mark Robinson, Peter Donnelly, and Walter Bodmer, ‘The fine scale genetic structure of the British population,’ Nature 2015 March 19; 519(7543): 309–314. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4632200/

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Angus Maddison, The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, OECD, 2001.

Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Gang Scandal, New English Review Press, 2016.

Tommaso Nannicini, Andrea Stella, Guido Tabellini, and Ugo Troiano, ‘Social Capital and Political Accountability,’ American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2013, 5 (2): 222–50. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.5.2.222

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

C. O’Madagain, M. Tomasello, ‘Shared intentionality, reason-giving and the evolution of human culture,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2021, 377: 20200320. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357000359_Shared_intentionality_reason-giving_and_the_evolution_of_human_culture

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Edward C. Prescott, ‘Lawrence R. Klein lecture 1997: Needed: A theory of total factor productivity,’ International economic review, (1998): 525-551. https://www.sfu.ca/~kkasa/prescott_98.pdf.

Jeffrey D. Sachs & Andrew M. Warner, ‘Economic Convergence and Economic Policies,’ NBER Working Paper 5039, February 1995. https://www.nber.org/papers/w5039

NK Tharshini, F. Ibrahim, MR Kamaluddin, B Rathakrishnan, N Che Mohd Nasir, ‘The Link between Individual Personality Traits and Criminality: A Systematic Review,’ International Journal of Environmental Resources and Public Health, 2021 Aug 17;18(16):8663. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8391956/

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

United Nations, Replacement Migration: Is it A Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?, Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs United Nations Secretariat,

21 March 2000. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd-egm_200010_un_2001_replacementmigration.pdf

"Open borders is great for humanity, but nevertheless awful for us."

I really wish Swift were alive to skewer this insane form of theoretical barbarism.

"Great for humanity" means it benefits a vague idealistic abstraction, this thing called "humanity", which is not really humans or peoples and their homes and homelands, but a signifier that only exists on a spreadsheet and in the minds of our academic priesthood.

Not to mention that Bryan Caplan didn't write this decades ago but after the verdict has long been in on mass immigration: We all know and see that all these supposed benefits only really accrue to the top ten percent/ownership class, who privatize the gains and socialize the losses. Are we all really still supposed to believe that it's socially beneficial to make GDP the paramount value, even if it results in massive social disruption and alienation? Even if it makes everyone miserable?

This is Soviet logic, where "humanity" is sacred but actual humans are expendable, especially the disobedient or "unproductive" ones.

👏People👏 are👏 not 👏interchangeable 👏widgets 👏