The failure of economists...

...On migration has been so bad, it may amount to criminal intellectual negligence

In a post on my Substack, I discussed how migrants from the Greater Middle East—the region from Morocco to Pakistan, the region conquered in the great wave of Arab conquests from 632 to 750—made poor migrants at so many levels, including being a net drain on the fisc of European welfare states. The most horrifying cost of such migration has been industrial-levels of organised sexual predation, with similar patterns across various countries, plus the infamous mass sexual assaults during 2016 New Year celebrations: these undertaken by members of a religion that sanctifies sex with captives.

This shows what ridiculous nonsense open-border economics is. People are not interchangeable widgets. People from different cultures, faced with the same set of possibilities and payoffs, make different decisions: hence the enormous difficulties exporting political institutions across cultural gaps. More people=more transactions=more gains from trade is a ludicrously simplistic way to look at the complexities of human interactions.

When you import people into a polity, that affects the dynamics of every aspect of the polity. You may be thinking you are importing workers, but that means you are importing people.

What moves this failure of economists from error to something akin to criminal intellectual negligence is that economic historian Robert Fogel published in 1989 a study (Without Consent or Contract)—republished in 1994, after he won the Nobel memorial—that explained in detail how mass migration, resulting from the development of steamships and railways, fractured the American Republic along its then fault-line of slavery. You have to be blind—or, apparently, an economist—not to notice that migration has been fracturing the UK, France and the US along their metropolitan/provincial (or cosmopolitan/parochial) divides.

Migration fractured the American Republic

Political, media and other systems are full of positional, or quasi-positional, goods: goods that cannot—or are blocked from—responding to increased demand through increased supply. Regulation can create more such goods: for example, by highly regulated land use inhibiting the supply of housing from responding to increased demand for housing, driving up rents and house prices.

The most obvious instance of such positional goods is the political system itself: there is only one President, Prime Minister, etc. Seats in legislatures may be redistributed, they are rarely increased. Migration dilutes the votes of any group functionally restricted to the existing polity.

The development of railways and steamships in the 1820s led to dramatically falling transport costs. This ushered in the first age of mass globalisation, which ended in 1914. We are living in the second such age, one that began in 1945. Ours was created by the American-led maritime order, just as the first was created by the British-dominated maritime order of 1815-1914.

The steam-powered mass migration to the—economically far more dynamic—Free States of the United States, than to the Slave States, turned the Slave interest into a permanent minority in the House of Representatives, was doing so in the Electoral College, and prospectively in the Senate. This led to intense struggles over the admission of new States to the Union.

Slaves represented perhaps a third of the total wealth within the Slave States. The Haitian Revolution—and the systematic massacre of Haiti’s European population in 1804—provided a worst-case scenario for the plantation elite. Even the decline in planter fortunes in the UK’s Caribbean colonies after Britain freed the slaves in 1833 —despite compensation payments to slave-owners—was not an encouraging example.

The plantation elite viewed as an existential threat a potential alliance between slaves and white “masterless men” within the Slave States—the growing number of lower class Euro-Americans who were systematically disadvantaged by a slavery system that economically and socially devalued their labour and raised land prices. This was precisely the potential alliance that the election of Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)—the first Republican President—threatened to produce. During the Civil War itself, areas dominated by those “masterless men” resisted Confederate secession from the Union, including violently.

Abraham Lincoln was not the first anti-slavery President. He was the first President to ally opposition to slavery to a program of tariffs and homesteading that was political catnip to the “masterless men” of the South.1 As President, he could appoint Republican organisers to federal positions throughout the Slave States that would enable such an alliance to be organised: especially if his federal Postmasters stopped blocking abolitionist literature.

Hence Lincoln’s election saw the secession of the Deep South and the US Civil War.2 Mass migration—by shifting political dynamics—fractured the American Republic along its fault-line of slavery.

More recently, Palestinian migration sparked a long civil war in Lebanon and a short one in Jordan. Indeed, one can view the Arab-Israeli dispute as arising out of migration.

Leaving things out

Economic analysis of migration has a persistent tendency to leave things out, such as the implications of endemic cousin marriage. The Morocco-to-Pakistan region has high rates of cousin marriage.

If you marry your cousin in one generation, no big deal. Do it for 50, for 70, generations—for a thousand, for fourteen hundred, years—it is a big deal.

Folk of Pakistani origin are four percent of British births and generate 30 per cent of British birth defects. That is the sharp end of a general sickliness from consanguineous (typically cousin) marriage that drives up health costs.

Bringing in lots of migrants raises rents and house prices when regulation retards housing supply. Migrants of very different cultural origins break up local social capital (networks and connections), making it harder for locals to respond to problems and opportunities or to force accountability on local politicians.

NIMBYism—using regulation to block new construction—is a lot easier to generate the more housing market entrants are non-voters (i.e. migrants). Increasing population increases the wish to protect local amenity, such as not blocking views or from other crowding effects. These patterns spiral up the more property dominates household wealth. So, migration not only drives up the value of land, it increases NIMBY pressures, generating surging rents and pushing home ownership out of reach.

In Australia, NIMBYism started in cities with geographical positional goods—Sydney, with its beaches and Harbour views and Adelaide with its Hills—and then spread to other cities as population growth increased the wish to protect amenity and State Governments took advantage of the tax revenue benefits of rising property prices. The notion that migration would not be a problem for rents and house prices if it were not for NIMBYism is classic not-thinking-things-through, not remembering that importing people affects all aspects of a society, including regulatory pressures.

Migrants with high levels of capital, particularly human capital (skills), tend to raise wages, as they make labour comparatively more scarce and raise the general productivity of the society. They do not suppress the Baumol effect—the tendency for competition for labour to transfer wage gains from increased-productivity sectors across the wider society. If anything, they enhance the effect. This is why haircuts cost far more in 2025 than they did in 1960 without any substantive change to the service provided.

Conversely, migrants to developed democracies with low skill levels (or other capital) tend to suppress wages, as they make labour more plentiful compared to capital and tend to lower the average productivity of the society, both of which act against the Baumol effect. What encourages investment in productivity is when the incentive is to add capital, not hire more cheap labour.

The notion that you can greatly increase the supply of something, and that will not put downward pressure on its price, is magical thinking. That downward pressure from increased supply of labour will not be realised if bringing it in increases demand for such labour more than the increased-supply effect—hence the importance of where the capital/labour ratio is going.

Nevertheless, the lower migrants’ human and other capital—so their expected income—the less increased demand effect there will be. This particularly so when suppressing the Baumol effect by bringing in lots of low-skill labour means that already-resident workers generate less demand than they otherwise would. Even more so if the influx of migrants raises rents—the return to land—due to regulation retarding housing supply, as has been happening.

The notion that bringing in (working) migrants who raise GDP so, as long as their impact on GDP is larger than their impact on public debt, you’re ahead, is nuts. First, why bring in such migrants at all? You are much better off selecting for migrants whose effect on both net government revenue and GDP is positive. This is even more so if who you are bringing in affects who is leaving. Britain bringing in low-skill migrants who are a net drain on the fisc while driving away the young and the talented makes its fiscal and GDP position worse.

Second, as noted above, low-skill migrants adversely affect your long-term growth trajectory; including the ability of existing residents to contribute to the fisc. Thirdly, it is a vastly inferior strategy to getting your budget under control directly. Britain in particular needs to have less resources going through its dysfunctional state apparatus, not more.

Fourthly—and sinisterly—the destruction of Liz Truss’s Premiership shows that a fiscally-stressed state is susceptible to public servants briefing media to thereby panic bond markets so that, by not intervening, the central bank can get rid of an inconvenient Head of Government. Democratic feedback mechanisms are already broken enough. We do not need even more reasons for electorates to think that conventional politics denies them any effective say. That is the path to the collapse of presumptive acquiescence to the norms of a polity (aka “legitimacy”) that—especially when a formerly demographically dominant group begins to feel threatened—leads to civil insurgency. An ever-increasing public debt is also an ever-increasing vulnerability.

Undermining fiscal, social, and political resilience all at once is a deadly combination.

Culture matters

Gathering information has a cost. Attention is a scarce resource. Cognitive capacity is limited. As a result, we are boundedly rational beings, that being what evolutionary processes produce. Fast-and-(cognitively)-frugal heuristics—ways of doing things: aka habits, customs, routines, prejudices, etc.—are often selected for. Indeed, a culture can be understood as bundles of socially-evolved life-strategies sharing various heuristics.

That gathering information has a cost, attention is a scarce resource and cognitive capacity is limited means we adopt varying strategies. Even in asset markets, people can develop varying trading strategies, depending on what they pay attention to, on their ability and willingness to pay attention, how they acquire and use information.

Cultures assemble, transmit and reinforce particular framings/patterns of belief (schemas) and patterns of action (scripts). These are reinforced by what registers as success in each culture, by the various normative social technologies—customs, conventions, social norms—the importance and types of various social connections, and so on.

Thus, cultures generate varying life-strategies and heuristics, so varying expectations. Variance in expectations, in social signals—plus simple ignorance—can generate considerable cultural distance and raise social transaction costs. Differences in levels of social trust are differences in expectations, including confidence in shared expectations, with lower trust leading to fewer transactions.

Cultural diversity increases the likelihood of social frictions and makes it harder to socially coordinate, which can affect, for instance, the ability to coordinate to provide new infrastructure. Migration plus restrictive regulation of land-use raising the price of land can thus depress provision of infrastructure. This also increases congestion costs.

Crime, particularly homicide, tends to be concentrated in “fiscal-sink” localities—localities with low or negative government revenue. High crime rates help make them fiscal-sink localities. Such localities tend to be under-provided with effective policing, compared to what is needed to achieve the same level of crime clearance (and so deterrence) as other localities.

If there are problems of cultural distance between police and local residents, it will be harder to police such localities. Importing people lacking in skills useful in a developed economy—and who are culturally distant from the wider society—sets up the inequalities, the steep/adverse status-hierarchies, and alienation from police, known to be conducive to creating high-crime localities, including ethnically-based gang violence.

The explosion in gang violence in Sweden comes from precisely these dynamics. With the addition of systematic suppression of identification of—or action on—ethnographically inconvenient crimes in the name of “racial harmony”, we also see these dynamics in the industrial-levels-of sexual predation across much of central and northern England. Cultural alienation between police and residents, along with concentrated inequality and adverse status hierarchies, have a great deal to do with the problems in France’s banlieues.

Cultural differences can mean importing sectarian politics, as Europe has been experiencing with clashes between supporters of Palestinians and Israel. Migration—both through who is imported and who is driven away—can be used to mould electorates: the so-called Curley Effect, though one might as readily call it the Blair Effect. Britain’s dysfunctional migration is helping to drive away the young and the talented, making its fiscal situation worse.

The Loury principle—that relations come before transactions; that we begin embedded in a series of social connections well before we start economically transacting—means social placement and cultural framings matter. Lack of cultural convergence, potentially across the entire range of human actions, has had some extreme consequences. Writer and commentator Louise Perry describes the most heart-breaking:

But this is hard history now, beyond dispute: police forces across the country prioritised the prevention of race riots over the prevention of the sexual torture of tens of thousands of children, and almost all of the media and political class turned a blind eye to it (with some important and admirable exceptions), precisely because the perpetrators were motivated by anti-white animus. That fact is so shocking, and so significant, that we cannot find the right words.

Mass sexual predation on under-age girls and women did not appear in the calculations of economists about the costs and benefits of immigration. It has become very much associated in the public mind with immigration.

All this has wider policy implications. Free trade has become coupled in the public mind with open borders (very unpopular) and mass immigration (also unpopular), to the serious detriment of the free trade and de-regulation cause. Classical liberals are losing, and will continue to lose, until they face up to the ways they got immigration seriously wrong. As a friend notes about free trade and immigration:

Classical liberals and even more libertarians did this to themselves. Tried to grab both [both free trade and open-borders immigration]; got neither.

Free trade is under a lot less pressure in Australia, because we have done immigration much more sensibly, so it is simply not generating the same level of social and political pressures.

The need for borders

Why do states have borders? It is all very well to say that public goods—services that are non-rivalrous (many folk can consume at once) and non-excludable (you cannot pick and choose who gets the service)—can be financed by taxes, but even privately provided public goods tend to be territorially based.

Public goods have a scope problem. Yes, you can fund them via taxes—coerced payment—but you still have an issue with who you tax and protect. This is a scope problem.

Both public providers (states) and private providers—e.g., private policing—typically solve the scope problem by, in effect, turning public goods into a giant club good—one with boundaries. They tax and defend this territory and folk from—and mostly in—said territory. This is the sharp end of how states create and maintain an institutional commons—a set of inter-locking institutions across a specific territory.

Citizenship ties folk to a particular state, to a particular institutional commons. Degrading citizenship via mass, unselected immigration; degrading citizenship by attempting to suppress dissenting voices; degrading citizenship by attacking the heritage that created that state, that institutional commons; are all mechanisms to undermine the resilience of that state, that society, that institutional commons. It creates a tragedy of the (political and institutional) commons—where people degrade a commons by under-investing in it while over-extracting from it. It is a giant effort to tear down the ultimate Chesterton’s Fence.

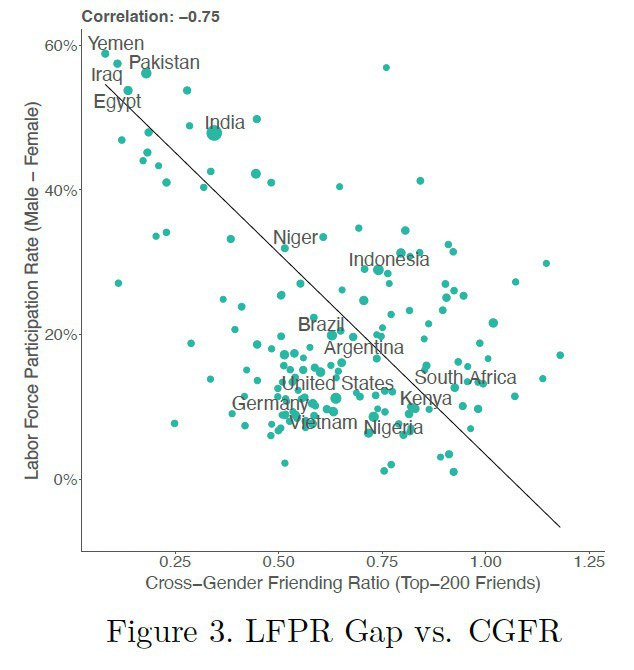

The ability of women, for instance, to have a high level of autonomy in large mass societies rests on plumbing (public and commercially available toilets), a respectful public order, and unilateral control over their fertility. These are creations of particular institutional commons and when societies import folk with very different cultural presumptions, there can be a serious regression in women’s access to public spaces.

How willing women are to venture beyond their immediate neighbourhood, or even out their front door, is a marker of the standing of women in a society. Muslim visitors to medieval and early modern Christian Europe regularly reported their astonishment at how many women were out and about in public and how respectfully the Christian men treated them. Much of the modern veiling movement in Islam—which started with educated middle class women who ventured beyond their immediate neighbourhood—is precisely about navigating public spaces via protective social signals in societies with particular cultural and institutional histories and patterns that still show very high levels of social segregation of men and women. Women who don’t veil send a different signal.

The sort of blind utilitarianism which rates all humans equally is deeply corrosive of citizen/non-citizen status-differentiation needed to maintain a robust institutional commons. If the problem of virtue ethics is that it does not scale up, and of utilitarianism that it does not scale down, neither grapples well with the identification across time, across the generations, that grounds an institutional commons.

An institutional commons is subject to tragedy of the commons, where people degrade the institutional commons by under-investing in it while over-extracting from it. The Western professional-managerial classes are being increasingly parasitic (i.e., over-extracting) while degrading democratic feedback and undermining any sense of binding heritage.

They are not so much under-investing in the institutional commons as actively debauching it, and using migration policy to do so. Convincing a formerly dominant group that migration will destroy their position in society is a great way to break an institutional commons—as the lead up to the American Civil War demonstrated.

Regino of Prum (d.915) came up with a fourfold definition of nation, based on Classical conceptions, that became the standard definition in medieval Europe:

Diversae nationes popularum interse discrepant genere moribus lingua legibus.

(The peoples of various nations differ by origin, customs, languages and laws.)

Genere (origin) here means ancestry. A lot of what is passed off in academic literature as racial differences are cultural differences, while racial categories can submerge significant cultural differences—e.g., in the US, between descendants of American slaves, Afro-Caribbeans, and recent African immigrants.

Folk can adopt new cultural/ethnic/national identities. Indeed, civic nationalism—the pioneer state for which is Republican Rome—is based on the idea that ancestry is not required for you to be a full member of the nation. Yet there is still a polity-community one is joining that needs to have—or construct—an anchoring set of robust expectations across time for its institutional commons to be resilient.

Not interchangeable widgets

Humans as socially-interchangeable widgets generated the notion—which the UN was pleased to call replacement migration—of importing people to replace the children who are not being born. Whether the replacements would behave in the same as those whose absence they would be making up for apparently did not need to be seriously examined. On the contrary, the view has been regularly pushed that they would make things better.

That they might make things worse was not something to be seriously entertained. It was a possibility that should have been taken much more seriously. It comes from valuing a narrow conception of efficiency and paying little or no attention to resilience.

Ludicrously inadequate “crank the handle” theories of economic growth also have done their bit to analytically misdirect. It is sobering to contemplate how much of Economics is blown up by a single sentence from a review article on the role of culture in the happenstance of human affairs:

Although using very different methodologies, the studies all provide evidence leading to the same general conclusion: individuals from different cultural backgrounds make systematically different choices even when faced with the same decision in the same environment.(Emphasis added.)

For instance, it blows up all theories of economic growth based on Cobb-Douglas production functions. The prediction of such Theories that economies will converge over time has not come true because both culture and institutions affect profoundly how and if factors of production are generated and used.

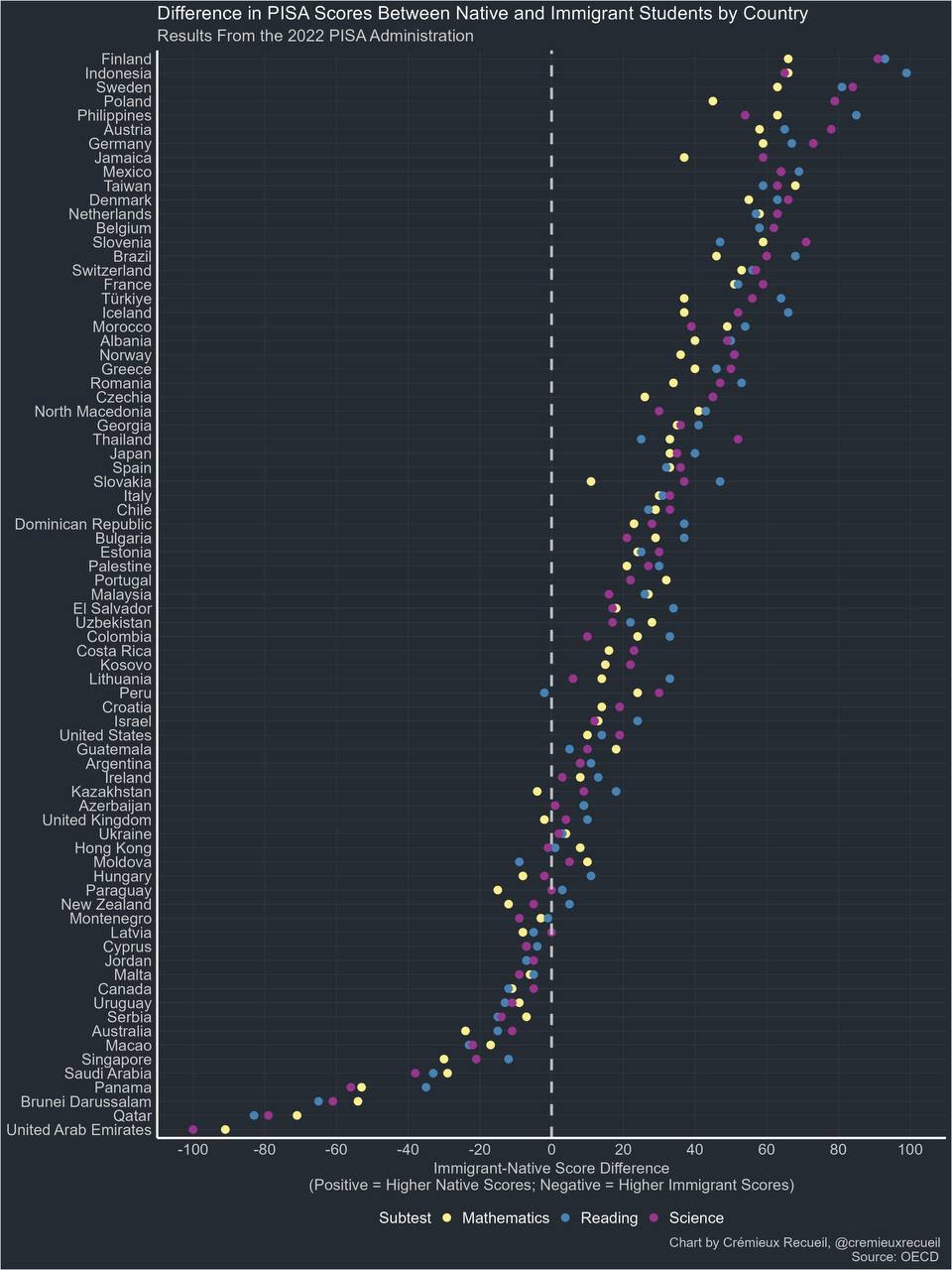

Indeed, cultural variance—not making the same decision in the same circumstances—is such that one can fail to get income convergence between different groups within the same polity. Hence we will and do get very different outcomes from different groups of migrants.

Efficiency serving resilience

Everything social is emergent from the biological. What is biologically selected for is lineage resilience—the ability of genetic lineages to continue across changes in circumstances.

All efficiency in biological organisms is selected towards achieving lineage resilience. This includes any particular biological system—such as perceptual and cognitive capacity. The selection is for good-enough efficiency. This is because what threats and opportunities are currently salient constantly shifts, so we respond by shifting attention and using different perceptual and other systems.

Of course we economise on cognitive effort, as our attention is a scarce resource that has to be able to deal with the shifting salience of threats and opportunities. Hence, we have such things as habits, customs, prejudices and routines—aka fast-and-frugal heuristics. You only really learn a skill when you can do it without paying conscious attention to it.

That attention is a scarce resource is why the money illusion exists—it economises on cognitive effort across monetised transactions to treat money as having static goods-and-services value. Like all such economising, it is a trade-off, which shifts when the the balance of costs and benefits shifts.

Efficiency is much easier to mathematise than resilience, and it’s precisely the failure to value social and institutional resilience that has led to dysfunctional—and potentially disastrous—migration policies.

There is not much point in living in an “efficient” polity if it’s not a resilient one. Even worse, not paying attention to the costs of cultural diversity means one increasingly gets both a less efficient, and a less resilient, polity. The UK currently displays what that looks like. Contemporary welfare states are proving themselves to be neither demographically nor fiscally resilient. Misconceived migration has been reducing their fiscal, and their social, resilience.

This is especially so when the professional-managerial class has been—by the non-electoral politics of institutional capture—blocking voters from having an effective say about migration policy. This prevents the feedback that is a great strength of parliamentary and democratic systems. But blocking such feedback is in the interests of the professional-managerial class, as it elevates itself as the allegedly superior decider—“we are masters of Theory, don’t you know”—while using, and elevating, social leverage through controlling discourse legitimacy—shrieking racism!, xenophobia!, Islamophobia!, etc.—and enabling institutional networks to evade accountability.

Much of the role of mainstream media has been to provide coordinating narratives, the current set of what to believe if one wishes to be of the Smart and Good. The collapse of the mainstream media audience share in favour of alternative media has increasingly weakened narrative control of public discourse.

The EU push against dis/mis/malinformation represents an attempt to regain narrative control. If you want to see what loss of narrative control looks like, Elon Musk destroying the ability of shouts of Islamophobia! to block serious discussion of industrial-levels-of sexual predation across England is a dramatic case in point.

It is a reasonable question why economists were not paying more attention to implications of demographic trends years ago, and why they are not paying more attention to the implications of different patterns of migration for financial, social and political resilience now. The short answer is economic Theory pays lots of attention to efficiency, very little to resilience.

Anywheres versus Somewheres

Inadequate economic analysis—such as we’ve seen with the way economists have treated immigration—is an example of a recurrent problem in academe: using Theory to sort and judge evidence. Economists paid attention to what their Theory suggested they pay attention to. Or to what it was comfortable to pay attention to.

There has also been an extra element, also common in academe: using mastery of Theory to dismiss the concerns of fellow-citizens, particularly working-class citizens.

This is the classic Anywhere/Somewhere divide delineated by British social analyst David Goodhart. The divide between those whose social capital—whose networks and connections—are based in a particular locality (Somewheres), and whose sense of self arises out of place, and those whose networks are not based in a particular locality (Anywheres). In addition, there are those whose sense of self arises out of credentials, out of mastery of Theory. Anywhere networks are often transnational. This tends to be especially true of academics.

From territorial to social imperialism

States, institutions and cultures all respond to patterns of constraints and capacities. The steep reduction in transport costs that railways and steamships represented led to a wave of European imperial expansion across Africa and Southeast Asia, as the costs of controlling and administering distant territories fell dramatically, while the trade that provides the revenue “cream” for imperial expansion greatly increased.

The steep reduction in communication costs from the telegraph and steam-powered printing and distribution then led to an unravelling of empire. For the subsequent creation of mass politics strongly encouraged and advantaged grouping by language group; by folk who could understand each other and were working off a broadly consistent set of social expectations. That there was very little economic benefit to the imperial metropoles from their colonies aided de-colonisation, helping the imperial unravelling.

The creation of a multi-cultural polity is an exercise in social imperialism, as it enables the professional-managerial class to play new games of favour-divide-and-dominate, to dissolve the demos into competing groups with variant expectations, life strategies, social scripts, and social schemas. If you import migrants who drive up use of welfare services, that increases the employment and policy authority of the professional-managerial class.

Multiculturalism-cum-identity-politics—such as asymmetrical multiculturalism—is the intellectual vehicle for this class imperialism. (One of Australia’s advantages is it is quite multi-ethnic, it is much less multi-cultural.)

By 2011, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and French President Nicolas Sarkozy had all declared multiculturalism a failure. Yet there was no retreat back to assimilation. Instead there was a massive surge in identity politics, because that suits the interests of the professional-managerial class.

Such demos-dividing, multiculturalist migration provides the excuse for the professional-managerial class to seek social leverage—amounting to social dominance—by controlling discourse legitimacy. The ability to shout racist! xenophobe! Islamophobe! etc., and to seek narrative control of public discourse, is key to this game. Hence the dramatic surge in the use of terms of moral abuse. Economists dismissing working-class resistance to migration as economic illiteracy have been very useful intellectual foot-soldiers for their class.

We begin to see the deep contradiction. The default assumption of mainstream economics is to see folk as rational decision-makers with complete information (or at least more information about their own circumstances than others possess). But not if they are working class folk disagreeing with their cognitively superior masters of economic Theory. Then they are obviously quite ignorant (cognitively inferior) and possibly implicitly or explicitly racist or xenophobic (morally inferior).

In reality, working class resentment of the flooding of their communities with newcomers is picking up something real, something that matters. This is without considering driving up rents. Cultural diversity undermines social coordination, so causing infrastructure and other congestion issues; it suppresses wages—not cutting, but suppressing wages; then there are fiscal-sinks creating increased crime in various localities.

All this does much to explain the rise in national populism. A lot of commentary by economists on migration conforms to trader and commentator Barry Stevenson’s acid comment on academic financial economists:

These guys are so bad, they’re unable to know they are bad.

The discounting of working-class voices for not speaking with the linguistic delicacy of the educated professional-managerial class is a classic iteration of that hardy historical perennial: dismissing the working classes as insufferably vulgar. There is, of course, a very prominent US political figure frenetically dismissed as insufferably and outrageously morally vulgar: one Donald J. Trump.

The attacks on Trump’s moral vulgarity did not separate him from working class voters, it drew them to him. He spoke, in so many ways, their language, their cultural touchstones. But Donald Trump—the wealthy builder—did something most of his working days that almost none of his outraged critics had. He talked to, and with, working-class people. Not only that, he did so about that most working class of activities—building things. He talked their language, their cultural language.

In Europe, mass migration has been used as a vehicle of social and cultural change that has actively denigrated the culture, heritage, and choices of (particularly) working-class residents. This has gone with the suppression—mainly by de-legitimisation—of working-class dissent, so that they are not able to derail the Grand Project.

This is highly congruent with the Ever Closer Union project of the EU which—as the valorisation of a particular future—judges the electoral choices of European citizenry on the basis of whether they “fit” with the Ever Closer Union Project (or not). The recent cancellation of the Romanian Presidential election looks very much like a case in point.

Dramatic changes in the ethnic composition of a locality impose genuine costs on the local residents. This is not a concern for “compositional amenity”, the bullshit term economist David Card and others use to patronise working class concerns. It is the disruption, dilution and loss of networks and connections—the degrading and loss of social capital—that seriously undermines the ability to manage risks and opportunities, to operate effectively as a community. Social capital has been a key element in how humans navigate the vicissitudes of life, all the way back to our forager origins: it matters.

Open borders explicitly strip working-class voters of any say over immigration, and not only immigration, as it seriously undermines the ability of working-class citizens and communities to participate in decisions with local impacts. That is much of the point of the refusal—as an Australian, I can testify that it is a refusal—to maintain borders. Meanwhile, some useful idiots fail to realise how much such stripping working class citizens of a say is the point of the politics and policy of immigration.3

It’s reasonable to characterise national populism as class politics. But it is class politics that Western elites started—that the social imperialism of the professional-managerial class started—and to which it represents a recurrent response.

What French economist Thomas Piketty so nicely calls the Brahmin Left is essentially the organisational politics of the professional-managerial class. They are a clerisy obsessed with linguistic taboos, with ever-expanding moral sins, and the expression of horror at moral vulgarity, at moral blasphemy. Their social and cultural imperialism—using migration policy and control over legitimacy of discourse as key instruments—has increasingly alienated working-class voters.

The latter’s shift towards national populism has suffered the usual problem of working-class politics—they are not an organising class. The professional-managerial class’s social imperialism (aka “wokery”)—including using state power via the administrative state, via private-public partnerships, to censor and to debank people, to cut them out of discourse, commerce and finance—has, however, pushed more organising talent towards the national populist cause.

Much of the Trump Administration’s organising talent is a direct reaction to the lawlessness of the Biden Administration. Then again, if you think your politics is distilled morality; that you and yours own morality—so all opposition to your politics is immoral—and that your politics should apply to all realms of life… then your politics are totalitarian, and lawlessness is the natural metier of totalitarian politics.

If this was totalitarian politics, what would we see? We would see commissars, political officers. We might call them DEI officers, bias response teams, intimacy consultants, sensitivity readers. We would see Lysenkoism, the corruption of science by ideology, where people are punished and excluded for their dissent. We might call this insisting that sex is non-binary, when no species reliant on gametes for reproduction produces more than two types (one large and sessile, the other small and motile).

We would see Zhdanovism, where entertainment—from film to games—is required to conform to set messages and narratives, with dissenters being punished and excluded. We would see purges, where folk are hunted down by ideology-enforcing mobs and sacked: we could call this cancel culture. We would see censorship: the notion that error has no rights and they can determine error. We can call this stopping mis/dis/mal-information.

We would see these things, if we were dealing with totalitarian politics. The politics of a class insisting that they own morality—so politics that resists their claims is immoral, so illegitimate—and their superior deciding capacity should operate in all spheres of life. That is what we would see. And anything that helped divide the demos—and de-legitimise their voices—would help such politics along.

A species with evolved mechanisms

Much of the problem with how economists have treated migration can be traced back to Samuelsonian Physics-envy Economics that wants to treat humans as economic particles whose behaviour can then be more readily mathematised. One such economic “particle” is much like another, and the more identical they are, the easier to mathematise.

Actual physicists who turn their attention to economics do rather better, because they bring an empirical rigour to the discipline that does not use pre-existing Theory to judge evidence. This paper on the effects of polygyny, co-written by a physicist, is a case in point. Futurist Samo Burja, using experience in tech and deep reading of history to analyse the life-cycle of institutions, is another. J. Doyne Farmer developing agency-based economics is yet another.

In reality, we are a specific, evolved species with a particular set of evolved mechanisms and adaptations that are general to us as a species but whose use is highly particular and path-dependent. We have prestige, which encourages behaviour that benefits third parties (positive externalities) and propriety (including stigma) that discourages behaviour that harms third parties (negative externalities).

We cope with Knightian uncertainty—when we cannot make individual calculations of personal loss or benefit—by engaging in the social calculations that we can still do, to minimise status risk (i.e., social risk) and to maximise our ability to react to information that others may acquire. Hence we see herd and flocking behaviour in markets that shift depending on whether current uncertainty is being read positively or negatively. (Bitcoin uncertainty is currently being read positively.)

Hence also increased information—that is, reduced uncertainty—can lead to asset prices falling. This happens if the new information revises downward how what was previously uncertain, and/or the remaining uncertainty, is read. Uncertainty means we cannot calculate into that space, hence we calculate around it instead.

The flight to safe assets—so a crash in transacting, so economic recession—one sees when expectations about total spending on output (so income) collapses is another form of shifting to where you can calculate. From 1992 to Covid, Australia had the longest recorded period of economic growth without a technical recession precisely because the policy of the Reserve Bank of Australia effectively anchored expectations about total spending (and so income).4 Expectations matter, a lot.

We are biologically embodied strategic agents acting across time where there is no information from the future. Hence, expectations matter pervasively. Macro economic policy in a monetised economy—where money is one side of almost all transactions—is about two things:

(1) Expectations about the future value of money—in terms of goods and services, i.e., output—because if we expect money’s output-value to fall (inflation), the incentive is to spend it, and if we expect money’s output-value to rise (deflation), the incentive is to sit on it, to not spend it.

(2) Expectations about the future path of spending (on goods and services), so income; for if we expect our income to fall, we will shift to safe assets, so transact less, so you get that crash in transactions we call a recession (or, it if goes on long enough, a depression).

Macro-economically, everything else is mere bagatelle. As the central bank, the monetary authority, is the expectations monster—money being one side of all monetised transactions—macro policy is mainly about what it does or does not do. In expectations terms, fiscal policy is an expectations midget, monetary policy the expectations giant.5

We Homo sapiens are highly normative,6 as that generates the robust, convergent expectations needed for higher levels of cooperation—so we can engage in the cooperative subsistence and reproduction strategies required to raise our very biologically expensive children. The “yes, that is yours” which is the basis of all property ownership and exchange relies on our normative capacity (your dog is as aware as you are of “what is mine”).

We humans are not Homo economicus, but Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees) playing strategy games in a behavioural lab are. That we are not Homo economicus—because we are highly normative; we have prestige and propriety to motivate and structure social interaction; we can manage shared intentionality; and generate convergent, even robustly convergent, expectations: for instance by what we refuse to trade-off against—is why there are billions of us bipedal apes and only thousands of our high primate cousins.

We are very much part of the social conquest of the Earth. We do it by our very distinctive version of ultra-sociality—through non-kin cooperation—rather than by eusociality—breeding non-reproducing helpers. Of course, thousands of generations of being normative organisms has also led to the capacity to game norms. Given our conscious cognition is a tiny fraction of our cognition, that includes being strategically self-deceptive in doing so.

One way to game our normative capacity is to claim that whatever goal one is pursuing is so grand it overwhelms normal moral constraints. We see this with the horrors of Marxism, and the toxic nonsense of Critical Theory and its derivatives. Western progressives—the dominant moral politics of the professional-managerial class—habitually use grand moral purpose to evade moral constraint: constraints such as accurate journalism, respect for fellow citizens, intellectual charity towards others.

The professional-managerial class—which includes economists—has proven very adept at moralising and rationalising their networked self-interest. This readily includes having way overblown tickets on themselves for their alleged mastery of Theory. Indeed, they are drunk on Theory—not merely as the lever to move the world—but because it is their lever. This is why we see frantic wailing if someone takes their toys away.

As Masters of Theory, they can aim for the golden future in their head, which makes them such splendid moral beings—such clever and knowledgeable moral beings. That future, being imagined, can be as perfect and pure as they want. By contrast, those benighted enough to defend the created past and lived present—so, actual human achievement—can be assailed with its inevitable imperfect trade-offs and sins; sins actual, imagined, and exaggerated.

Why Economics is not a science, social or otherwise

The overwhelming majority of the economic benefit of immigration goes to the migrants themselves. The overwhelming majority of the remaining fraction of economic benefit goes to the holders of capital—including the (credentialed) human capital and networked social capital of the professional-managerial class.

Workers get so little of any economic benefit from immigration that it takes very little for local providers of labour to lose from immigration. There are so many ways local providers of labour lose from immigration as it actually operates—particularly from low-skill immigration, especially Greater Middle Eastern immigration—that such immigration can only be supported as a form of economic, cultural and social warfare against local workers.

Economists are not specifically responsible for the professional-managerial class in Britain preferring to retain control over discourse—being able to yell “racism!, xenophobia!, Islamophobia!”—rather than show elementary moral concern for thousands of sexually abused minors. Nor are economists responsible for the efforts of the professional-managerial class across the West to block or bypass democratic feedback.

Economists are, however, responsible for the view that to question the value of the immigration that folk were actually experiencing was a form of economic illiteracy. They are responsible for over-emphasizing efficiency and under-considering resilience. They are responsible for theories of human action and decision that pay little or no attention to the evolved structure of human cognition. They are responsible for not sufficiently considering cultural transaction costs. They are responsible for poorly considering the issues of managing each country’s institutional commons.

This is especially true of American economists ignoring a prominent—a Nobel memorial laureate no less—economist explaining how mass migration had previously fractured the American political order. That is, mass migration stressed the existing US institutional commons along its slavery fracture-line so that it collapsed into what is still the bloodiest war in US history.

Mass sexual exploitation of minors does not appear to have entered into the calculus of the costs of immigration. Many of the other ways that immigration has ended up bring used as a weapon against the resident working class do not appear to have entered into that calculus, either.

If you import workers, you get people and people affect every aspect of a polity. This does not seem so hard to understand. Unless, of course, you treat people as economic “particles”, whose differences are insignificant. Yet both biological and cultural evolution proceeds via difference, via differentiated outcomes. For people from different cultures, faced with the same set of possibilities and payoffs, make different decisions.

Everything social is emergent from the biological. The social sciences have had 166 years since the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, and 154 years since the publication of The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871, to make themselves consilient with evolutionary biology. With a few honourable exceptions—notably, evolutionary anthropology—they have failed to do so.

Any social science that is not consilient with evolutionary biology is not a science. It is merely pretending to be such.

When they make mistakes as catastrophic as mainstream economics has with migration—by treating migrants as interchangeable widgets, as interchangeable economic particles—these are mistakes measured in fiscal failure; social dysfunction; the degradation of democracy and discourse; surging crime in afflicted localities; in thousands of sexually predated upon girls and young women. Any claim on the attention, let alone the taxes, of their fellow citizens has to be massively discounted. Especially if they continue to behave in a “nothing to see here” way; if they continue to be so bad, they are unable to know how bad they are.

References

Robert P. Abelson, ‘Beliefs Are Like Possessions,’ Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 16, 3 October 1986, 223-250. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1986.tb00078.x

M. Ajaz, N. Ali, G. Randhawa, ‘UK Pakistani views on the adverse health risks associated with consanguineous marriages,’ Journal of Community Genetics, 2015;6(4):331-342. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4567984/

Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano, ‘Culture and Institutions,’ Journal of Economic Literature, 2015, 53(4), 898–944. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.53.4.898

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Prey: Immigration, Islam, and the Erosion of Women’s Rights, HarperCollins, 2021.

Scott Atran, Robert Axelrod, Richard Davis, ‘Sacred Barriers to Conflict Resolution,’ Science, Vol. 317, 24 August 2007, 1039-1040. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1144241

Nicholas Barberis, Robin Greenwood, Lawrence Jin, Andrei Shleifer, ‘Extrapolation and bubbles,’ Journal of Financial Economics, Volume 129, Issue 2, 2018, 203-227. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/extrapolation_bubbles_published_version.pdf

Jan van den Beek, Hans Roodenburg, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, ‘Borderless Welfare State - The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances,’ 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371951423_Borderless_Welfare_State_-_The_Consequences_of_Immigration_for_Public_Finances

Abdulbari Bener, Ramzi R. Mohammad, ‘Global distribution of consanguinity and their impact on complex diseases: Genetic disorders from an endogamous population,’ The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 18 (2017) 315–320. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110863017300174

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

George Borjas, ‘Immigration and the American Worker: A Review of the Academic Literature,’ Center for Immigration Studies, April 2013. https://cis.org/Report/Immigration-and-American-Worker

Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith, Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Migration, First Second, 2019.

David Card, Christian Dustmann and Ian Preston, ‘Immigration, Wages, and Compositional Amenities,’ Norface Migration Discussion Paper No. 2012-13, February 2012. https://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/immigration-wages-compositional-amenities.pdf

Jean-Paul Carvalho, ‘Veiling,’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 128, Issue 1, February 2013, 337–370, https://www.eief.it/files/2010/10/carvalho.pdf

Satyajit Chatterjee, ‘A theory of asset price booms and busts and the uncertain return to innovation’, Business Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2011, issue Q4, 1-8. https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/frbp/assets/economy/articles/business-review/2011/q4/brq411_theory-of-asset-price-booms-and-busts.pdf

European Commission, Projecting The Net Fiscal Impact Of Immigration In The EU, EU Science Hub, 2020. https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/projecting-net-fiscal-impact-immigration-eu_en

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018.

Mohd Fareed and Mohammad Afzal, ‘Genetics of consanguinity and inbreeding in health and disease,’ Annals Of Human Biology, 2017 Vol. 44, No. 2, 99–107. https://www.academia.edu/33934871/Genetics_of_consanguinity_and_inbreeding_in_health_and_disease

J. Doyne Farmer, Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World, Allen Lane, 2024.

J. Doyne Farmer, and J. Geanakoplos, ‘The virtues and vices of equilibrium and the future of financial economics,’ Complexity, (2009), 14: 11-38. https://arxiv.org/pdf/0803.2996

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989] 1994.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, Vol.85, No.1, Feb. 1977, 59-77. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/260545?journalCode=jpe

Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´inez-Toledana, Thomas Piketty, ‘Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages In 21 Western Democracies, 1948–2020,’ The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol. 137, 2022, Issue 1, 1-48. http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/GMP2022QJE.pdf

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Ryan James Girdusky and Harlan Hill, They're Not Listening: How the Elites Created the National Populist Revolution, Bombardier Books, 2020.

Edward L. Glaeser and Andrei Shleifer, ‘The Curley Effect: The Economics of Shaping the Electorate,’ The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, Vol. 21, No. 1, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/curley_effect.pdf

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

Mark S. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties,’ American Journal of Sociology, Vol.78, No.6, (May 1973), 1360-1380. https://snap.stanford.edu/class/cs224w-readings/granovetter73weakties.pdf

Mark S. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233. https://www.csc2.ncsu.edu/faculty/mpsingh/local/Social/f15/wrap/readings/Granovetter-revisited.pdf

Martin Gurri, The Revolt of the Public And The Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium, 2014.

M.F. Hansen, M.L. Schultz-Nielsen,& T. Tranæs, ‘The fiscal impact of immigration to welfare states of the Scandinavian type,’ Journal of Population Economics, 30, 925–952 (2017), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-017-0636-1

Ella Hill, ‘As a Rotherham grooming gang survivor, I want people to know about the religious extremism which inspired my abusers,’ Independent, Sunday 18 March 2018. https://https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/rotherham-grooming-gang-sexual-abuse-muslim-islamist-racism-white-girls-religious-extremism-terrorism-a8261831.html

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Paul Krugman, ‘It’s Baaack, Twenty Years Later,’ February 2018, https://www.gc.cuny.edu/sites/default/files/2021-07/Its-baaack.pdf

Timur Kuran, Private Truths, Public Lives: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification, Harvard University Press, [1995] 1997.

Bernard Lewis, The Muslim Discovery of Europe, W.W.Norton,[1982] 2001.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Gang Scandal, New English Review Press, 2016.

C.F. Martin, R. Bhui, P. Bossaerts, T. Matsuzawa, & C. Camerer, ‘Chimpanzee choice rates in competitive games match equilibrium game theory predictions,’ Scientific Reports, 2014, 4, 5182. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262885591_Chimpanzee_choice_rates_in_competitive_games_match_equilibrium_game_theory_predictions

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Stephanie Muravchik, Jon A. Shields, Trump’s Democrats, Brookings Institution Press, 2020.

Tommaso Nannicini, Andrea Stella, Guido Tabellini, and Ugo Troiano, ‘Social Capital and Political Accountability,’ American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2013, 5 (2): 222–50. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.5.2.222

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

C. O’Madagain, M. Tomasello, ‘Shared intentionality, reason-giving and the evolution of human culture,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2021, 377: 20200320. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357000359_Shared_intentionality_reason-giving_and_the_evolution_of_human_culture

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Paulina Restrepo-Echavarría and Brian Reinbold, ‘Has Australia Really Had a 28-Year Expansion?,’ St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Sept. 26, 2019. https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2019/september/australia-28-year-expansion

Philip Carl Salzman, Culture and Conflict in the Middle East, Humanity Books, 2008.

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Polygamy, the Commodification of Women, and Underdevelopment,’ Social Science History (2021), 46(1):1-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354584406_Polygamy_the_Commodification_of_Women_and_Underdevelopment

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Scott Sumner, The Money Illusion: Market Monetarism, the Great Recession, and the Future of Money, University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Scott Sumner, ‘Some Observations on the Return of the Liquidity Trap,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Winter 2002), 481-490. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/2002/1/cj21n3-8.pdf

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

United Nations, Replacement Migration: Is it A Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?, Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs United Nations Secretariat,

21 March 2000. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd-egm_200010_un_2001_replacementmigration.pdf

Joan C. Williams, ‘What So Many People Don’t Get About the U.S. Working Class,’ Harvard Business Review, November 10, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/11/what-so-many-people-dont-get-about-the-u-s-working-class

What was later racialised into Jim Crow—under-providing policing services, using poll taxes and public order convictions to block voting, extra-judicial murder via lynching—was originally developed to suppress the “masterless men”. A 2011 study found that counties in the U.S. South with more Scotch-Irish immigration prior to 1790 have higher homicide rates today, a relationship that only exists in the U.S. South. Culture-institutional interactions can be remarkably persistent. Hence the US having regional cultural ethnicities.

President Trump has thus taken the Republican Party back to its starting point—a protectionist Party suspicious of foreign interventions relying on working class votes—while the Democrats have transmuted from the Party of masculine brutality (slavery) to the Party of feminine cruelty (cancel culture).

Bryan Caplan’s discussion of “keyhole” solutions to various problems of migration in his Open Borders graphic primer is positively sophomoric in its political blindness. It goes with his—at least as sophomoric—lack of any sense of history and ludicrously narrow moral and social analysis.

As the Reserve Bank’s monetary target was of two-to-three per cent inflation on average, over the business cycle, that meant that the Reserve Bank would curb spending on output (NGDP) if inflation surged but encourage such spending if output started slackening. That effectively anchored expectations about inflation and total spending on output (so income). Even during the Global Financial Crisis—which, in part due to Australian prudential regulation, bypassed Australia—there was no flight to safe assets in Australia, so no crash in transactions, so the Great Moderation continued for Australia until Covid. Australia still has a business cycle, just a much flatter one than it used to have. (There was a golden period when Australia’s banks had the same total value as all Eurozone banks.)

Yes, there is the argument about liquidity traps. To the extent they exist, they are creations of public policy generating dysfunctional expectations.

Those lacking such normative capacity are regarded as personality disordered. The C19th term of morally insane conveys this sense of pathological departure from the normal pattern of humanity.

Thank you, thank you so much for taking the time to painstakingly research and write this pivotal piece of commentary.

MSM and academia has gone dark on so many of these finer details surrounding immigration that we're unable to have genuine and informed discussions about this matter with so many of our fellow citizens across the West.

Your overall thesis on the failure of economists on migration describes something that has been on my mind to a tee.

We live in such an immoral, trepidatious age that is defined by cowardice!

The article is so well written that I could quote the whole thing tbh, but I'll settle for this:

"The default assumption of mainstream economics is to see folk as rational decision-makers with complete information (or at least more information about their own circumstances than others possess). But not if they are working class folk disagreeing with their cognitively superior masters of economic Theory. Then they are obviously quite ignorant (cognitively inferior) and possibly implicitly or explicitly racist or xenophobic (morally inferior)."