I set up Not On Your Team, But Always Fair in July 2021. I did so because I was seriously annoyed with Facebook over a seven day ban for sharing a picture of some risqué Roman art from Pompeii.

Yes, I know that makes me sound like an old fart (I suppose I am an old fart). And I admit, these days, posting anything on Facebook makes me feel like I’m playing air guitar in a retirement home parking lot.

Thing is, Facebook had been my scratch-pad for working out ideas in advance of publication in newspapers and magazines for most of a decade. I had (and have) a good group of smart and interesting friends, the sort of people who made insightful comments, pointed me towards things I didn’t know, or challenged my assumptions.

I did (idly) wonder if Substack could take over from Facebook, but it must have been a particularly idle thought. I didn’t write anything here until November 2021. My production thereafter was ad hoc, sporadic, and featured a disproportionate amount of my cat.

However, by 1st December 2022—without much effort or thought—I had amassed a thousand subscribers. Substack had taken over the scratch-pad role I’d always reserved for Facebook, without me noticing.

It had also introduced 1,000 + people to Lorenzo Warby, who is the real reason I’m now motivated to grow Not On Your Team, But Always Fair to enormous size.

Two cancellations

Lorenzo has his own Substack, but I have a much larger, ready-made audience. There are historical reasons for this.

Many years ago, both Lorenzo and I were on the receiving end of cancellations. The one directed at Lorenzo succeeded, and he was driven out of public life. The one directed at me failed, making me more popular than ever.

Much of the difference in outcomes turned on my connections and professional experience, which struck me as both inevitable and unfair. I tried over a number of years to reintroduce Lorenzo to public life and commentary. This included him writing for a blog I ran, and me promoting his writing using my big Twitter account. Neither strategy succeeded.

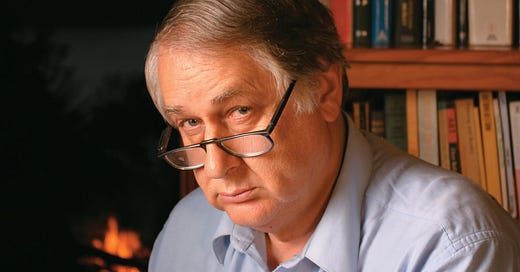

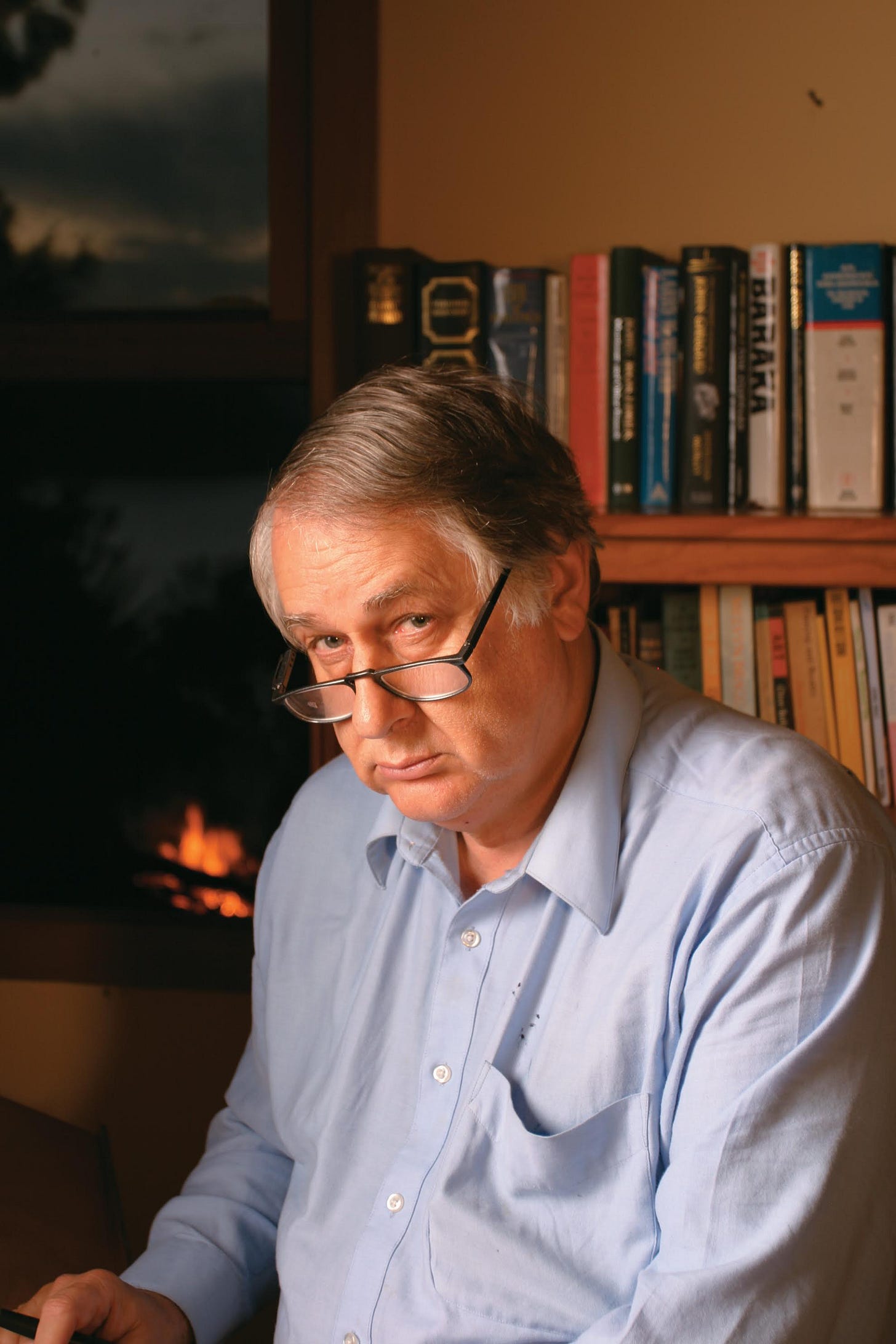

Information about my attempted cancellation is available all over the Internet, and not only from me. You can read or hear from both friends and enemies—and all sorts of people in between—going back decades. Four books were written about my literary controversy: one hostile, one friendly, one a collection of commentary from all kinds of people with all sorts of views, and one plain weird.

Lorenzo’s story

Lorenzo really did disappear from view, and with his permission I’m going to tell you what happened to him. By way of background, it’s worth knowing that both our cancellations—failed and successful—happened in Australia in the same decade. They form part of the global “political correctness” phenomenon that emerged in the late 80s and early 90s, and which faded away by the beginning of the twenty-first century (only to reappear in more virulent form circa 2010).

In the late 1990s, Lorenzo was a rising young star in right-wing think-tank-world, working for Australia’s Institute of Public Affairs. Australia has too small a population for dedicated classical liberal or conservative think-tanks, meaning right-leaning intellectuals are forced to spend company with people they often find uncongenial. Classical liberals care, for the most part, about economics. Conservatives—Lorenzo is one—often have a stronger interest in literature and the arts.

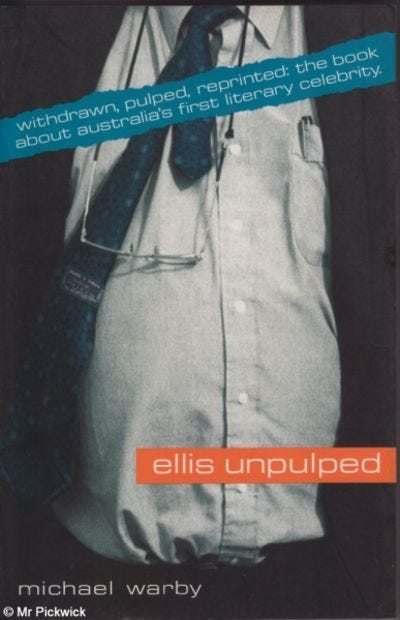

As part of his “culture” remit, Lorenzo was commissioned to write a literary biography of writer (and important Australian Labor Party figure) Bob Ellis.

If you look at Wikipedia’s entry on Ellis, you will note its brevity, despite an extensive back catalogue across multiple artforms. Now he’s dead, it can seem to foreigners that he was a minor figure. While he was alive, this was not the case. He bestrode Australian literature like a colossus. What Lorenzo uncovered when researching him explains a great deal of why Ellis has faded from view.

As he compiled his biography, Lorenzo kept coming across persistent allegations—from both friend and foe—that Ellis was a sleaze and a pervert, with a liking for “the young stuff”. Given his brief was to write a literary biography, Lorenzo excluded everything of this nature on the grounds that much of it was scuttlebutt. He included only one sexual allegation: that Ellis had attempted to pressure one of his lovers into procuring an abortion.

This, Lorenzo thought, was amenable to proof. He also thought it significant in a wider context because Ellis—like many figures in the Labor Party’s Catholic wing—was vehemently anti-abortion.

Ellis himself had been on the receiving end of multiple defamation suits for what professor of law Matthew Rimmer calls his “unreliable political memoirs”, one of which chased its own tail through two appeals and cross-appeals.1

However, when confronted with Lorenzo’s book—while he didn’t immediately sue—Ellis made an enormous public stink about the abortion allegation.

“One, however, on page 166, is the worst lie a Catholic can publish of another human being,” he thundered, “that he sought the murder of his child in the womb when in fact he saved her life and can prove it. I append the note regarding it, and a lawyer’s letter will follow.”2

Note, Lorenzo has no faith (although he understands religious sensibility, as his writing on here shows). Ellis conflated him with his Catholic publisher, Michael Duffy, as though the book’s actual writer lacked an independent existence.

No concerns notice (the first step in defamation litigation) had been sent, but Lorenzo’s publisher nonetheless recalled the biography and pulped it. Lorenzo resigned from the IPA. An attempt to capitalise on the controversy by reissuing the book with the abortion allegation removed failed to ignite. The damage had been done.

In despair, one of Ellis’s victims contacted Lorenzo after his book was withdrawn, distressed that Ellis was “going to win again”.

Skeleton disco

As happens to us all, Ellis died—many years later, in 2016. And, as often happens, all his skeletons came tangoing out of the closet.

Both sisters allege they had underage sexual encounters — one was an alleged indecent assault — with Ellis.

Kate claims she had sex with Ellis four times when she was 15 and 16 and still living at home. There was no coercion, “just an understanding that he wanted to have sex with me and I just did … whenever he turned up, he’d have sex with me. I didn’t at the time think that was some big, terrible thing … I was reasonably neutral about it. I didn’t hate him.”

She recalls one of those encounters in a new poem, Chattel, while in her book Rozanna writes of how Ellis allegedly forced her “reluctant fingers” inside his “verbose Y-fronts”. That poem is called Come Here, Child.

Rozanna says Ellis was simultaneously a friend and supporter: he tried to secure her film work and hired her as a school holiday nanny, thus adding to her confusion about the art scene’s sexual ethics.

The two sisters in question were playwright Dorothy Hewett’s children. Their mother, they said, ran “a brothel without payment,” prostituting her daughters to various artistic, libertine, Bohemian friends. Ellis was one of many. Both women wrote books about their experiences.

Ellis’s posthumous reputation was destroyed.

And yes, while it’s true the men in question committed the child sex offences—a point Dorothy Hewett’s son (and fellow Miles Franklin Award winner) Tom Flood made forcefully—Hewett “put them (his sisters) into that milieu […] They were the times, and men were taking advantage of it.”

This mild double-standard explains Ellis’s truncated Wikipedia entry, and Hewett’s fulsome one.

“This is not some out-of-the-blue attack on our mother,” Kate said. “People have acted like this is big news but [mum] wrote about this constantly. It was all openly discussed with her.”

This, of course, was precisely what Lorenzo found during his research—all of it on the public record. Such was the terror of defamation writs in Australian publishing at the time, however—and there were scores of them, as this backgrounder points out—Lorenzo was never given a chance to defend his claim.3

Having one’s book recalled and pulped on the back of a defamation writ is the worst thing that can happen to a writer, although writers do come back from it. One would think—and at the time, I did think—Lorenzo would be one of those people. Perhaps even an updated version of his book would be published, given its timeliness.

This did not happen. Lorenzo was never welcomed back into the fold. I suspect this was down to his conservatism. Arts and letters is the only place the far left has been able to dominate in Australia the way it dominates, say, the US tertiary or UK non-profit sector. There has only ever been room for a few conservative and classical liberal voices (I’m one of the latter, and widely disliked).

Lorenzo finished up in genuine poverty, eking out a living in call-centres, his immense talent wasted. For what it’s worth, I always thought a book about Bob Ellis was beneath him, but writers have to start somewhere.

What we’re doing here

There are now three-and-a-half thousand of you, and while—at least initially—most of you came because you wanted to read more of me, of late that interest has started to shift. People are coming for Lorenzo’s essay series, and although I can’t prove it, I think it’s his series that led to Not On Your Team, But Always Fair attracting Substack’s attention.

As I’ve said from the outset, I want Lorenzo’s essays between covers, preferably hard ones. I have been a (successful) professional writer and editor for long enough to know high quality literary scholarship when I see it. Yes, the series still needs work. Lorenzo is aware one essay needs to be rewritten. Another reason for publishing the series on Substack—apart from building an audience, that is—is the way it allows Lorenzo to respond to public commentary and polish his writing as he goes.

Substack also means he can earn money and rebuild his literary career. He desperately needs a new car—he’s currently driving around in a 15-year-old banger—which is something I’d like to see happen before Christmas.

The relaunch

To that end—and as a way of getting me off my freckle—this Substack is hereby relaunched today. Want to help Lorenzo buy a car? Subscribe here before September 9th and get 25 per cent off if you make an annual payment.

Why September 9th?

On September 9th—at 12 noon BST—Lorenzo and I will do the first in a series of Zoom chats for paid subscribers only. Yes, I know I promised this ages ago. Yes, I’m aware I haven’t done it yet. The main reason for my failure is fear borne of utter technical incompetence.

A couple of hours before Lorenzo and I go live, a link will be sent out to paid subscribers, both old and new. We will continue to do calls regularly, aiming for weekly later in the year. We’ll talk mainly about the essays, but also other things that come to mind, as well as respond to questions.

The Zoom calls

Now, about the Zoom calls.

First, expect the first few to be a bit wobbly. I am brutally untechnical. I have producers to help with my Liberty Fund podcasts and appearances on UK and Australian television/radio; they hide my ineptitude. Please bear with me. I will improve if people are patient.

Secondly, all calls will be unrecorded and run on Chatham House rules. No information from or quotation of—and this doesn’t just apply to Lorenzo or me—is to be attributed to any participant in the call, outside the call. Breach of this rule will mean a permaban and my eternal enmity. And lawyers are bad enemies.

Finally, I have become heartily sick of people’s off-the-cuff, spitballing remarks and casual comments being used against them years later. Both Lorenzo and I have been on the receiving end of vicious campaigns to destroy our professional careers, and consider people who do this morally deranged.

If we invite you into our literary salon, trust us when we say you can speak your mind.

This is serious, voters.

Abbott and Costello v Random House Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 137 ACTR 1; and Random House Australia Pty Ltd v Abbott (1999) 167 ALR 224.

Professor Matthew Rimmer’s account of the controversy—written before Ellis died—is neutral and, in my view, definitive. He has made it downloadable (for free) from SSRN.

“The Pulping of Ellis UNPLUGGED” The Weekend Australian, 19-20 May 2001 pg. 21, 24-25 Section: Inquirer.

Ellis often claimed that he would never sue because “I do not believe in it”. However, this was untrue. When Sydney Morning Herald journalist Kate McClymont wrote about him fathering a child on another man’s wife, he threatened to sue her personally, as well as her newspaper employer. You’ll need to scroll down to the second of the two articles (both about Ellis) extracted.

Lorenzo has been a revelation and your hypothesis is true in my case, but I pretty much had to subscribe after reading "And I admit, these days, posting anything on Facebook makes me feel like I’m playing air guitar in a retirement home parking lot."

I'm sorry Lorenzo has been put through the wringer like that, and I'm glad to get to read his fabulous essays through this substack. Good luck with the inaugural Zooming. I can't join this one but hope to join one in the future.