Where do we go from here?

The first of two pieces on our time of policy decay

I have never been to Minnesota. I have not read much about Minnesota. But, as I listened to a political and economic refugee from Minnesota talk about—with pain you can hear in her voice—the experiences that drove her and her husband out of the State, it was clear enough what was going on. For history may not repeat, but it sure does rhyme.

The massive corruption and welfare fraud being unearthed in Minnesota, the media culture that hid—and so facilitated it—and the intolerant opinion culture that went with both, is part of a much larger story across the Western democracies.

From social democracy …

From 1945 to 1973, the Western democracies were dominated by various versions of a social democratic policy regime. Expanding commerce and global trade—as the technological advances of the 1930s and 1940s were commercialised—funded expansion in social programs.

Welfare states became larger and more generous. Higher education expanded. With the mid c20th Baby Boom, fertility rates supported this vista of ever-greater mass prosperity funding an ever-expanding welfare state.

The fundamental idea of the 1945-1973 social democratic policy regime was that the existence of a developed society generated unearned benefits, so it was proper for the state to tax—or otherwise capture (e.g., by nationalised industries)—those benefits and distribute them more evenly.

The so-called Bretton Woods system was the international corollary of the social democratic policy regime. Exchange rates were tied to the US$ which was tied to gold. Capital flows were regulated to enable expanded trade while preserving policy sovereignty. The social democratic policy regime was very much a policy regime of nation-states, both politically and economically.

Economist Dani Rodrik pointed out—in a 2002 paper—that:

We want economic integration to help boost living standards. We want democratic politics so that public policy decisions are made by those that are directly affected by them (or their representatives). And we want self-determination, which comes with the nation-state. This paper argues that we cannot have all three things simultaneously. The political trilemma of the global economy is that the nation-state system, democratic politics, and full economic integration are mutually incompatible. We can have at most two out of the three.

The social democratic/Bretton Woods policy regime was to pick the nation-state and democratic politics while foregoing full economic integration.

The GATT system (1947-1995) facilitated trade. The US offered access to its markets—the apparently insatiable consumer demand of its ever-larger and ever-richer middle class—as the economic carrot for joining the Western alliance and supporting the US naval hegemony that underpinned the maritime mercantile order.

Nevertheless, there were distinct limits to such economic integration. The European Common Market (1957-1993) pushed against such limits and came up against social democratic resistance and critique of such integration. Complaints about the European Entity’s “democratic deficit” emerged from centre-left social democratic critiques.

The trouble is, policy regimes decay. As they implement their solutions to various policy dilemmas, the dilemmas to which they have no solution—or the dilemmas caused by policy decisions—or simply dilemmas from changes in circumstances, mount. This pattern is all the stronger in a time of technological flux—both of physical and social technology.

The massive postwar economic expansion rested on cheap and reliable energy—as expanding mass prosperity has since the application of steam power to transport via railways and steamships in the 1820s. The 1973 oil price rise had a contractionary effect, as a pervasive and adverse, supply shock.

The gains from the technological advances of the 1930s and 1940s ran out of puff. This meant that productivity growth dropped. As economist Milton Friedman had predicted in 1968, the apparently reliable trade-off between unemployment and inflation—you could have less of one by accepting more of the other—stopped working. Western economies got more and more of both unemployment and inflation—the dreaded stagflation.

So, a new policy regime was needed.

… to neoliberalism …

There was one on offer. This was what became known as the neoliberal policy regime. Neoliberal has become a much used-and-abused term. For our purposes, it simply means expanded use of market mechanisms.

Public sector firms were corporatised and privatised. States stopped setting prices or quantities across a whole range of markets, a process known as deregulation.

Commercial patterns and rhetoric were applied much more across the public sector—not necessarily with appropriate care. Trade protection was wound back, with trade becoming much freer.

Capital controls were wound back or abolished, fostering global integration of capital markets. Monetary policy focused much more on controlling inflation.

If productivity could not be improved by adopting new technology, it could be increased by adopting more efficient institutional arrangements, widening markets and expanding human capital and access to capital flows generally.

The fundamental idea of the neoliberal policy regime is that more transactions are good—as that means more gains from trade. Transaction costs should therefore be reduced so that there are fewer frictions that inhibit transacting. By this logic, immigration is inherently positive, as it means more transactors, more gains from trade. While not based on the same comparative advantage logic as free trade—though it analytically rhymed somewhat—immigration rhetorically naturally melded with it.

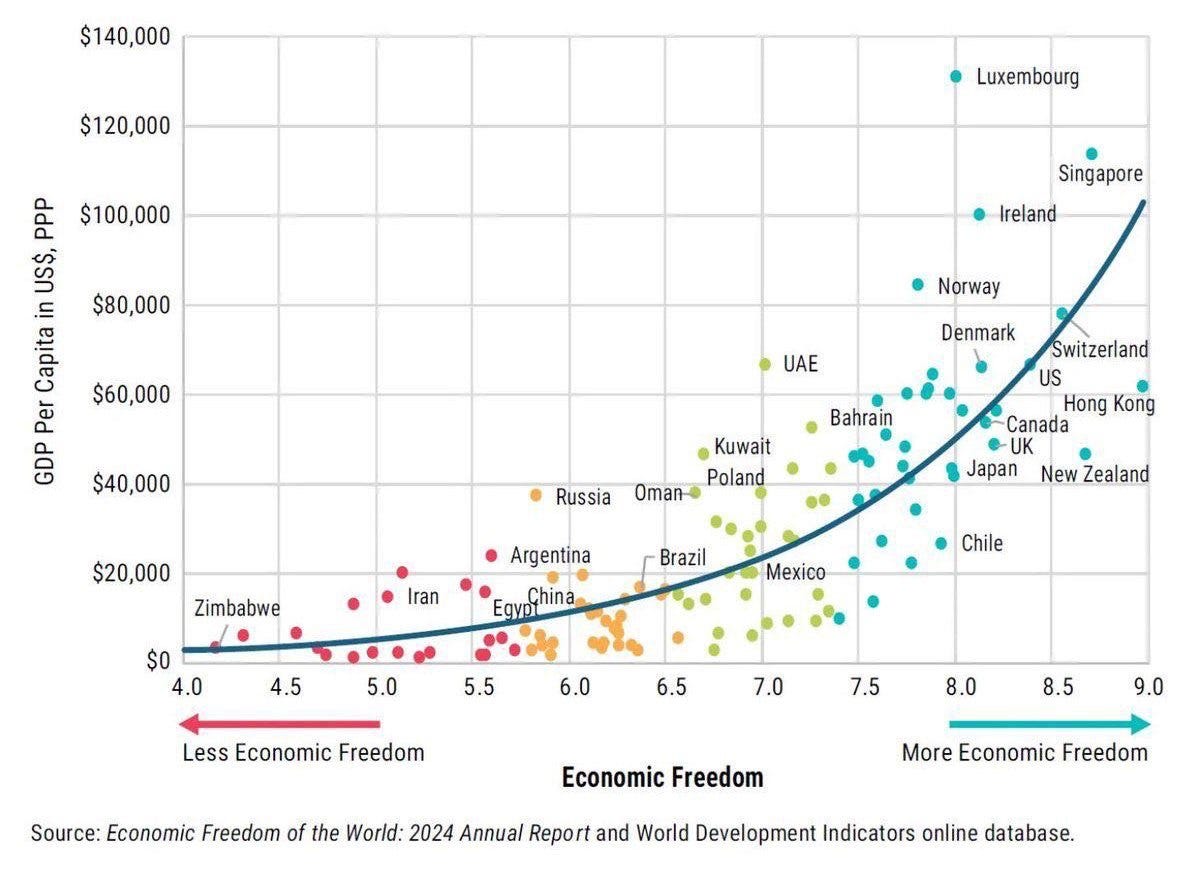

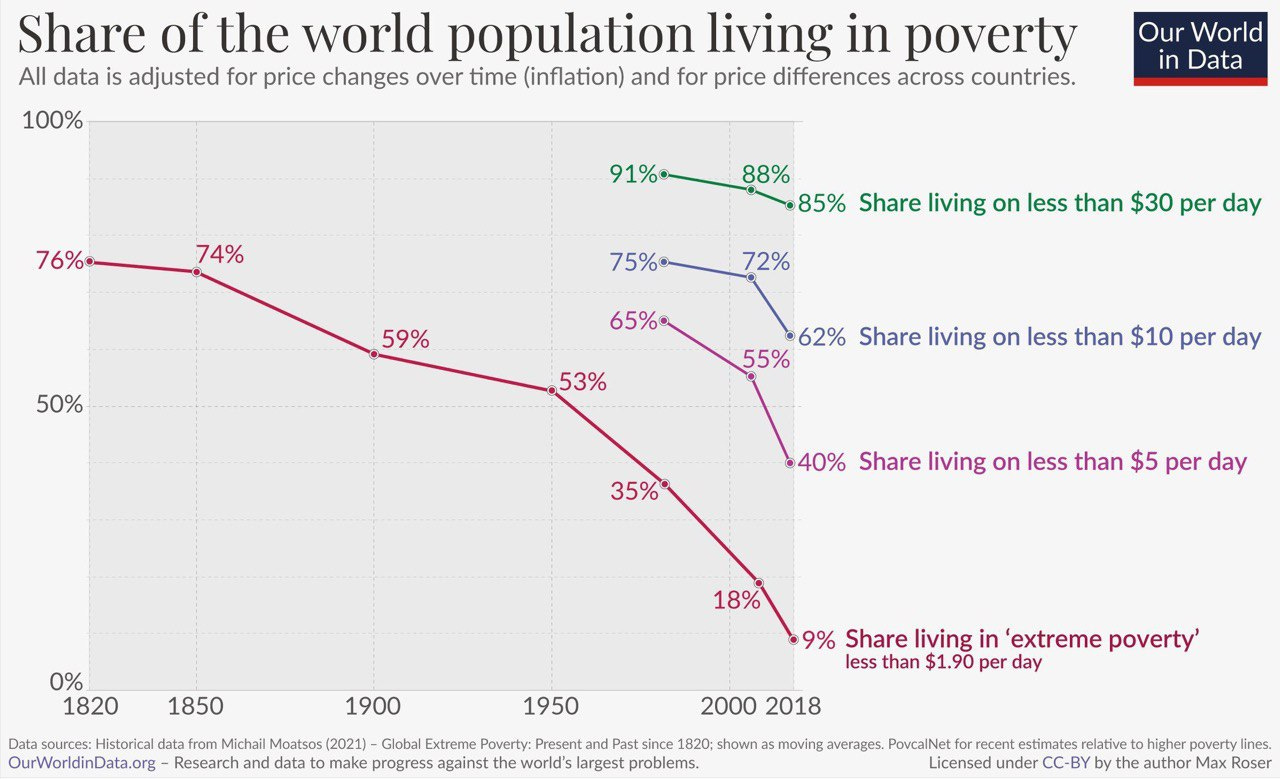

There are several things to note here. First, the neoliberal policy regime worked. There was a surge in economic growth. There was also a long period of macroeconomic stability—the Great Moderation. There was the largest movement out of mass poverty in human history.

Secondly, the new policy regime did not replace the social democratic institutions in the Western world, it was added “on top” of them. Centre-left Governments and politicians embraced the new policy regime precisely so that the social democratic welfare state could be paid for by improved productivity and economic efficiency.

Thirdly, there was a decisive break in policy circumstances in 1991, with the end of the anti-Soviet Cold War. The collapse of an existential threat to the Western democracies meant that Western elites lost much of the incentive to not alienate their working classes.

In 1993, the European Economic Community (EEC) became the European Union. In 1995, the GATT became the WTO. There was a sharp shift towards institutional globalisation after the end of the anti-Soviet Cold War.

Globalisation sought economic integration, so sacrificed nation-state economic self-determination. Yet democracy only operated at the nation-state level. Despite the pretensions of the European Parliament, there was no substantive updating of democratic governance. On the contrary, there was increased international elite coordination and a notable shift of policy away from popular preferences, especially on immigration.

In terms of Rodrik’s aforementioned institutional trilemma, neoliberalism chose economic integration over democracy. Nation-states were not abolished—as he points out, different value sets between nations mean they differ in how their institutions develop. Such institutional arrangements become self-reinforcing over time and it remains much easier to enforce contracts within, rather than across, jurisdictions.

Such self-reinforcing differences were all part of connections and information flows being much denser within, rather than across, jurisdictions. Indeed, one of the big social, political and cultural divides within developed democracies is between those whose connections—so social capital—are highly localised (“Somewheres”) and those whose connections are not (“Anywheres”).

Nevertheless, there was a push to technocratically expand economics and shrink politics, at least regarding economic policy. In the UK, there was active replacement of democratic feedback by devolving policy to quangoes and elevation of human rights legislation (which elevated judicial decision-making over democratic feedback). This was, however, an extreme version of a more general pattern of common integrative policy via international bodies and the administrative state. This pattern came to extend across policy areas.

The UK was simply a particularly blatant version of technocratic managerialism using human rights, international law, and international organisations as trumps over democracy. The non-electoral politics of institutional capture grew as playing to elite status-games proved much more effective than the harder ask of persuading voters. This was especially so given the liberal-conservative delusion that institutions can be trusted to run themselves.

With voluntary voting, it is relatively easy to drive working class voters away from the polls. The developed democracy which was highly neoliberal in its policy choices—yet remained relatively deferential to working class concerns—was Australia, due to the combination of compulsory voting and preferential voting. Mass immigration to Australia was not a creation of neoliberal globalisation but a deliberate postwar populate-or-perish program of nation-building that had been argued out in public.

Fourthly, there came to be an awareness in policy circles that the collapse in fertility rates had long-term implications—especially fiscal implications for funding the welfare state. Hence, in 2000, the UN came up with what it called replacement migration—bring in immigrants to replace the children that were not being born.

Fifthly, the neoliberal policy regime was based on a policy binary—markets (i.e., commerce) or the state. It represented something of a resurgence of classical liberal ideas—which were, in their original form, blank slate ideas—but in a narrow, technocratic form. Mainstream Economics—especially in its Samuelsonian “social physics” form—naturally treats people as interchangeable “social particles.” That makes the maths much easier.

So, there was no problem with replacement migration as the incoming immigrants would be the same sort of economic “social particles” as the locals. Immigrants and locals were interchangeable social widgets who would transact in predictable ways and grow the economy through gains from trade.

A false binary

The trouble is, none of this policy binary was true. Precisely because value is subjective, you cannot neatly separate culture from incentives. We humans cognitively map significance, not facts. Different cultures cognitively “map” the social world differently, hence people from different cultures will behave differently in the same circumstances because, in patterns of significance—so cognitively—they are not the same circumstances.

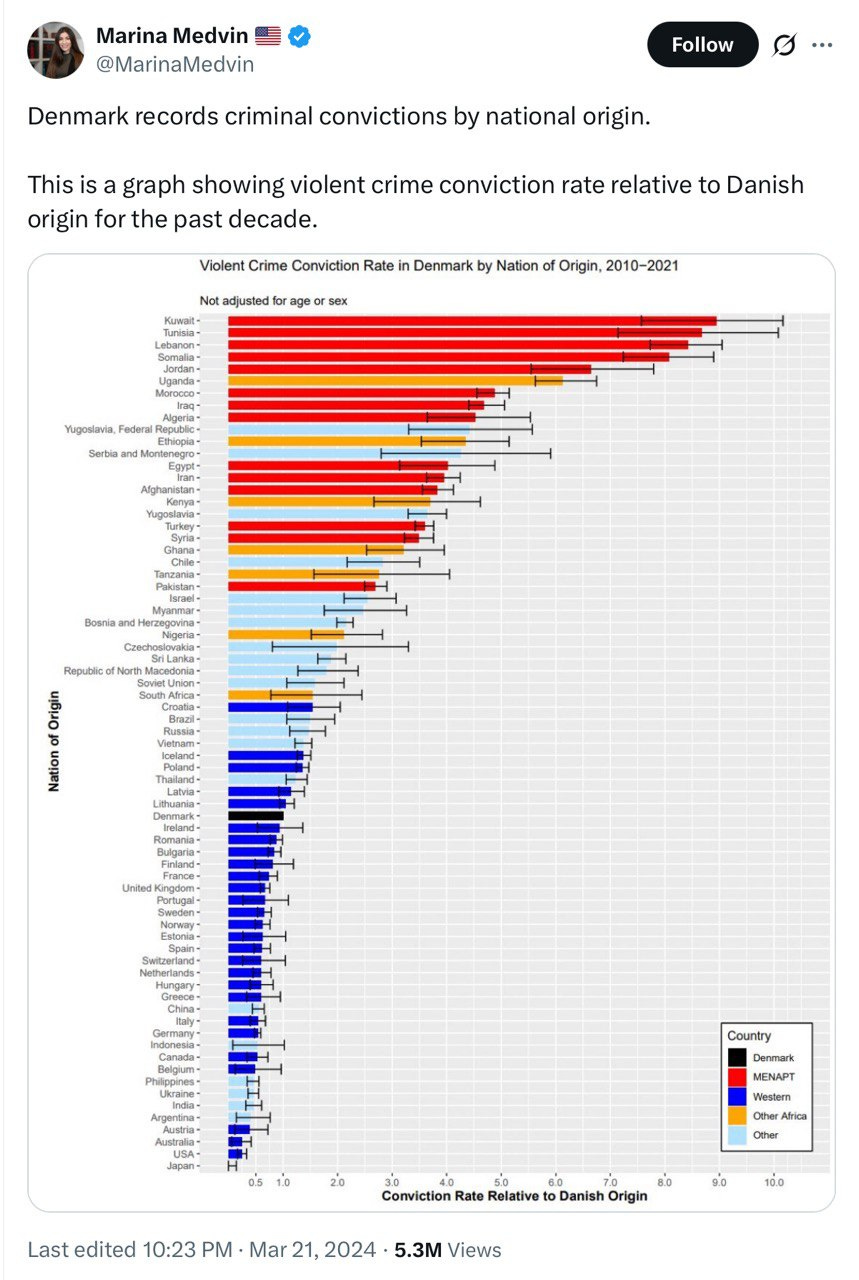

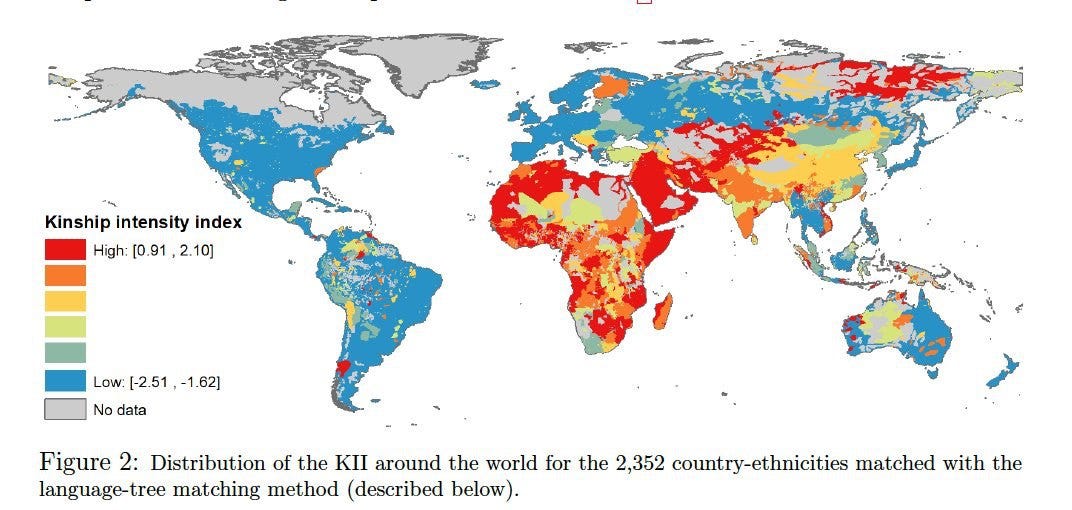

People display distinct cultural patterns. Thus we see Somalis in Minnesota treating the American welfare state as Somalis in Somalia treat foreign aid: you say whatever you need to non-Somalis in order to get the outsiders to hand over money, that you then channel to your clan. Somalia is a highly collectivist, highly clan-based, culture and the correlation between how collectivist cultures are and how corrupt states are is 0.91.

The stupidity was expecting that mere movement to the US—or any other Western liberal democracy based on far more individualist cultures—would lead to different behaviour. It was even more stupid to allow entry in such large numbers that their existing cultural patterns would be that much more reinforced.

Yes, institutions create incentives, but only if their rules are enforced. The demands required for well-functioning US (or Swedish or …) institutions were not enforced. Instead, the DEI-mentality—including the sacralisation of “people of colour”—married to political patronage, meant that (in both Minnesota and Sweden) Somali cultural patterns continued to operate and to corrode local institutions.

Such sacralisation of “people of colour”—extending to failure to enforce the rules, interacting with Islam’s legitimation of rape—is why the UK ended up with a massive Muslim “grooming gang” problem while Australia crushed its local problem. See Louise Perry’s excellent discussion below.

But we are back to the Australian political system incorporating working class concerns. The British elite, meanwhile, is systematically contemptuous of its working class and their concerns. Britain’s Blair-and-after moralised technocratic managerialism both expresses—and provides cover for—such contempt.

As I have discussed previously, that one can walk into any shop, market, bazaar in the world and recognisable conventions for property and exchange apply—and that commerce has strong profit-loss-risk-management incentives—has systematically encouraged economists to overstate the underlying similarity of human motives and so to understate the significance of cultural differences.

People with shared cultures will behave differently in different institutional circumstances, provided the institutions generate sufficiently powerful incentives. But people of different cultures will behave differently within the same institutional order. People who are well aware of differences between groups within the US seem to somehow discount or ignore differences between groups from outside the US.

Noticing substantive differences between human groups goes against Samuelsonian “social physics” economics, which analyses humans as interchangeable social particles. Such social physics—as a general analytical presumption—extends beyond loss-gain-risk commercial incentives only if people are blank slates.

The sharp divide over immigration is between those who—whether or not they realise it—are operating off blank slate presumptions and those who are not. Thanks to our toxically incompetent universities, blank slate claims have acquired normative dominance among Western elites.

The discourse on immigration dominant among Western elites operates as if both immigrants and locals can be treated as interchangeable social widgets—hence, one can analyse immigrants in an undifferentiated way—using normatively-dominant blank slate presumptions. The dissenting discourse treats differences between human groups—including cultural differences—as being analytically significant. This flagrantly violates blank slate presumptions.

Blank slate delusions

Newsflash, we are not blank slates. There are all sorts of differences between humans—both as individuals and groups—that matter, whether genetic, cultural or in other personal traits.

If we Homo sapiens are products of evolution, we cannot possibly be blank slates. For instance, we—along with Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees)—are the most proactively aggressive of the primates. We and chimpanzees are the primates most likely to deliberately kill fellow members of our species. We humans are also, however, the least reactively aggressive of the primates. We are the primates least likely to immediately respond to another member of our species with violence. Chimpanzees. . .are not.

As those forms of aggression use different brain circuits, the most plausible explanation for this pattern is that—across many generations—beta males combined to systematically kill off the alpha males (those high in reactive aggression). In other words, we murdered our way to niceness.

We greatly reduced our propensity to reactive aggression, but we did not eliminate it. Indeed, reactive aggression continues to dominate patterns of homicide. Meanwhile, our propensity to proactive aggression was not selected against: we remain the equal most proactively aggressive of the primates.

These trends were about selection pressures. Hence the propensity to violence varies greatly between and within human groups due to a mix of genetic, other biological, cultural and institutional factors.

For example, males (particularly young males) overwhelmingly dominate perpetrators of violence (except against children). Human toddlers are very physically aggressive and have to be socialised out of such aggressiveness. As philosopher Hannah Arendt famously said:

Every generation, civilization is invaded by barbarians—we call them ‘children’.

Any notion that humans are naturally benign and peaceful souls is nonsense on stilts. We have the capacity to be, and often are, such. This, however, depends hugely on context. This is why levels of violence can vary so greatly by locality—even within the same city.

From the high medieval period to around 1900, there was a dramatic fall across Europe in violence and homicide rates that started in Atlantic littoral Europe and spread South and East. This is what sociologist Norbert Elias called the civilising process—i.e., the becoming-more-civil process.

Not all cultures have gone through this, or a similar, process. This means that cultures vary dramatically in their rates of violence—even without considering other differences in genetic selection pressures across millennia.

One is supposed to be very impressed, for example, with Australian Aborigines having inhabited the Australian continent for roughly 65,000 years. One is not supposed to ask what specific selection pressures operated across those 3,000-and-counting generations—with continuing consequences. Nowadays, Aboriginal metabolic health is disastrous. They’ve been going through the simultaneous metabolic disasters of the Neolithic farming revolution—which farming populations took millennia to adapt to, and is something that we Homo sapiens have never fully achieved—and the modern processed food revolution, in very few generations.

If one is operating off the blank slate presumption, consequences from differing selection pressures does not even arise. Worse, raising the question is illegitimate.

Noticing inconvenient differences between human populations is a horrible sin in blank slate world. For, without inconvenient differences—and especially noticing inconvenient differences—our blank slate sameness would enable ultimate social harmony to be achieved.

Homo sapiens have gracile features because of our low rates of reactive aggression. So, one would expect that human populations with more gracile features (e.g. East Asians) would have lower rates of reactive aggression and human populations with less gracile features—Sub-Saharan Africans and Australian Aborigines—would have higher rates of reactive aggression across human jurisdictions.

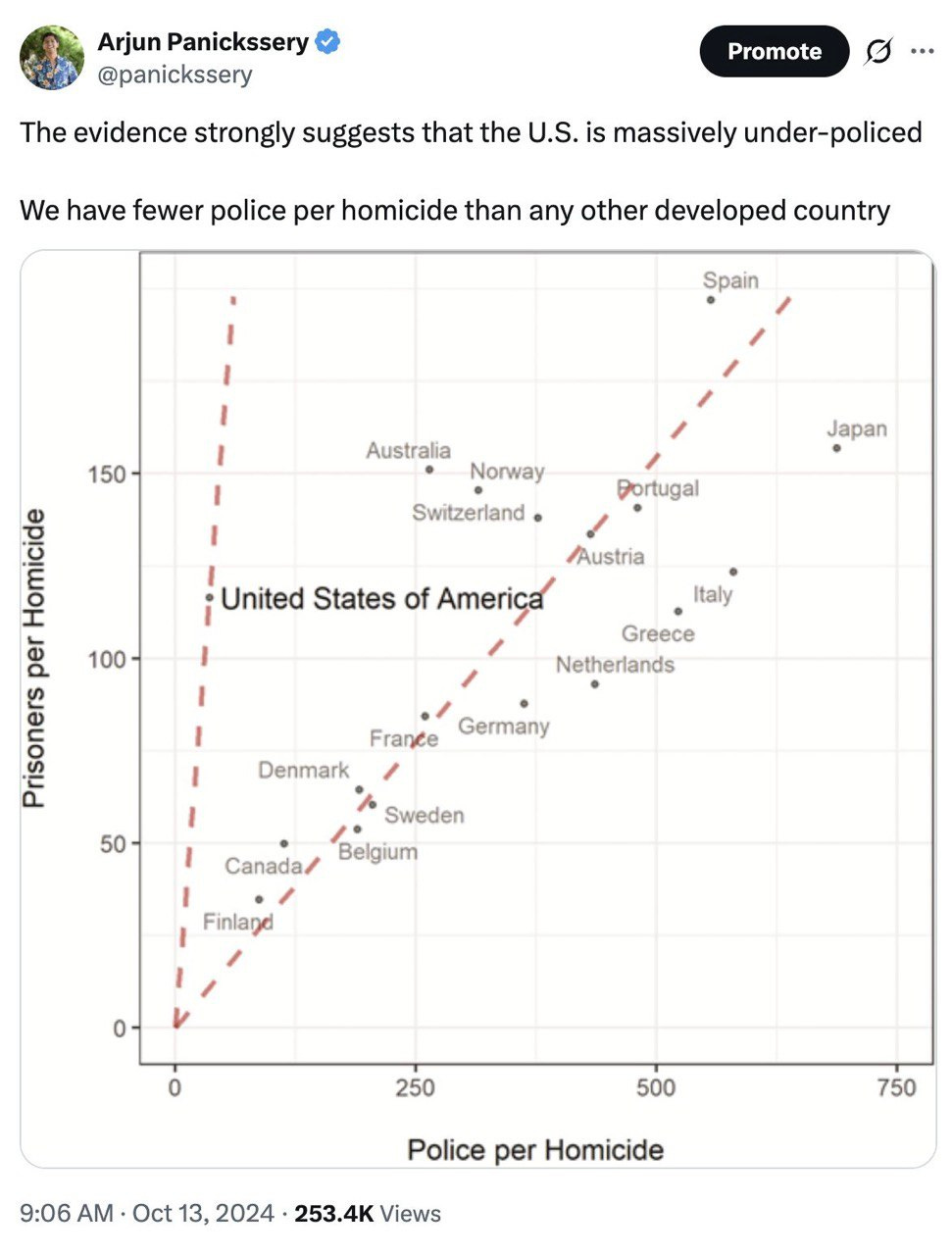

This is indeed what we observe but—thanks to the blank slate delusions having normative dominance amongst Western elites thanks to our toxically incompetent universities—neither voters nor those making public policy are supposed to notice this. It is one of the reasons why, for example, the US is dramatically under-policed.

We are a distinctively cultural species because we are the blankest slates in the biosphere. But our very nature as cultural beings—and that our brains are structured for us to be cultural beings, including structure to learn rules and norms readily—generates a whole new set of differences between human groups. Cultures generate different maps of meaning, differing patterns of significance. This operates on top of any differences in distribution of genetic traits due to different selection pressures across millennia between human groups.

The liberal delusion

So, the notion that we are blank slates who—through the application of our reason—will all become good little liberals if we are just exposed to liberal ideas, is delusional. Liberalism is the product of a very particular cultural matrix. Practical liberals such as John Stuart Mill were always aware of this. (Mill holding senior administrative positions in the British East India Company aided his awareness of cultural difference.)

Alas, liberal theory has, from its origins, been couched in universalist terms that readily deludes itself about not being a product of a particular cultural matrix. The various Lockean, Hobbesian and Rousseauian states of nature are not remotely accurate descriptions of pre-state human societies.

To take just one failure, all of them presume an absence of kin-groups. These were absent from European societies as a result of their deliberate suppression across millennia by first Classical Greek city-states and the Roman Republic/Empire, and then by the Christian Church—particularly in manorial Latin Europe.

This suppression had cultural and institutional consequences that were invisible to liberal and proto-liberal theorists and are still invisible to many Westerners. In particular, it lead to a cultural individualism that was quite specific to European Christendom and its offshoots. Liberal theory has universalised it precisely because of a delusional philosophical anthropology—borrowed, in large part, from the religion—while being utterly unaware of the distinctiveness of its own civilisational history.

Rousseau is wrong about so much it is hard to know where to start. He is wrong about property, which does not rest on mine! but on yours! All mine! does is create as contestable territoriality. Your dog can do it as well as you can—try taking his bone. It is acknowledgment by others of yours! that creates the conventions of property, of rights-to-decide.

Human toddlers have to be socialised into yours! They get mine! rather more easily. But they are remarkably easy to socialise into shared rules precisely because we are not blank slates. They are primed to pick up language—because they are primed for rules and norms—but have to be taught literacy and numeracy, which are entirely cultural creations.

Human sociality is not incidental and reason-based—as Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau claim. Human sociality is fundamental and rests on our emotional and normative cognitive architecture. That is what is so scary about psychopaths—part of that primed cognitive architecture is just missing.

Systematically killing off the highly reactively-aggressive alpha males greatly aided the development of human sociality. Hence we observe that the more gracile, less reactively aggressive, human populations show more robust sociality than the less gracile, more reactively aggressive, human populations. This absolutely creates differences that matter for immigration policy.

Open borders advocacy requires the blank slate delusion, as it requires there are no differences between human groups that are corrosive to a liberal social order. This claim is false.

The next post explores further the decay of the postwar policy regimes and the lack of a clear alternative.

Great post. One observation on the Somali/Minnesota issue from someone with a bunch of Minnesotans via marriage in my family, and why in my view there couldn’t be a more disastrous location for their settlement…Minnesotans are the most passive people I have ever met in the face of unpleasantness or getting taken advantage of. They hate interpersonal conflict and will take almost any slight silently rather than be openly confrontational. So importing a bunch of aggressively grasping clannish primitives to this state led directly to them brazenly ripping off taxpayers while also becoming a political power center. None of my relations regardless of politics have ever had anything good to say about Somalis over the past 25 years but now that Trump is going after them they are suddenly “members of our community” that are being unfairly maligned. It obviously doesn’t register that Somalis most certainly do not recognize white Minnesotans as members of their own community or any group they should treat with respect.

"Thus we see Somalis in Minnesota treating the American welfare state as Somalis in Somalia treat foreign aid: you say whatever you need to non-Somalis in order to get the outsiders to hand over money, that you then channel to your clan."

It's absolutely true that this dynamic is in play.

But there's one more factor: hawala. Somalis don't use a conventional banking system. When they want to send money from the U.S. to Somalia, they literally fill suitcases full of cash and a courier takes them to Somalia on a passenger plane.

Wouldn't that be a handy step in laundering federal funds through the Somali fraud mechanism, then moving it to Somalia in a suitcase, then finding ways to port it back into party coffers?

Isn't it possible that crooked politicians in the U.S. went to the Somalis and helped them set up their fraud machine, then used hawala as a way to route the funds back to their party, with everyone along the line getting a cut?

Isn't it possible that protecting this racket (and others yet to be uncovered) is why MN politicians are so overly zealous about thwarting ICE?

Sending activists to physically impede LEOs as they carry out operations that their political opponents promised to implement -- that's breaking the social contract! If you lose the election, you fight via political channels to stop the winners from getting very far with their agenda.

Something is very wrong in MN, and I'm guessing it involves 12 digits.

Yup, at least 12.