Our postcolonial trash needs taking out

Few famous books are as wretched as 'The Wretched of the Earth'

For my sins, I had to study a “postcolonial theory and literatures” (note the plural) subject as an undergraduate. This was in 1992. Thanks to skilled use of my Marijuana Model of Intellectual Merit—aka “The Bong Scale”—I managed a high distinction and the subject prize.

Each week, I read the material, stone cold sober, and tried to make sense of it. I often disagreed with its claims, and would (sometimes) set out alternative views in tutorials or small-group seminars. I did try to disagree (with Michel Foucault) in one piece of assessment for another theory subject and was saddled with a poor result. I am intellectually vain and dislike bad marks.

My method thereafter was simplicity itself.

15 minutes before I had to sit an exam in any theory subject, I would toke up. A proctor once told me I smelt like a pot plantation as I went to take my seat in some exam hall or another. In the six theory subjects required of me to graduate, I finished up with five high distinctions and a distinction. I kept local weed dealers in profits on the way, though.

Lorenzo Warby is older than me, as subscribers have probably noticed. One beneficial effect of this is that he studied humanities and social sciences disciplines in the late seventies and early eighties, long before—at least in Australia—the universities had turned into nonsense factories. He didn’t read the Ur-texts of what he calls “post-Enlightenment progressivism” as an undergraduate. Instead, he’s reading them for the book he’s writing, bringing his distinctive “everything social emerges from the biological” lens to bear.

At ’s and my request, Lorenzo added Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth to his reading pile, a thoroughly unpleasant book we both had inflicted on us as postcolonial theory undergraduates—as paid subscribers who came to the last Zoom chat now know. I described Fanon as “rapey” in one seminar while Katy tried to take him on in an assignment, paying a steep price marks-wise.

Meanwhile, what follows below is Lorenzo’s assessment of The Wretched of the Earth.

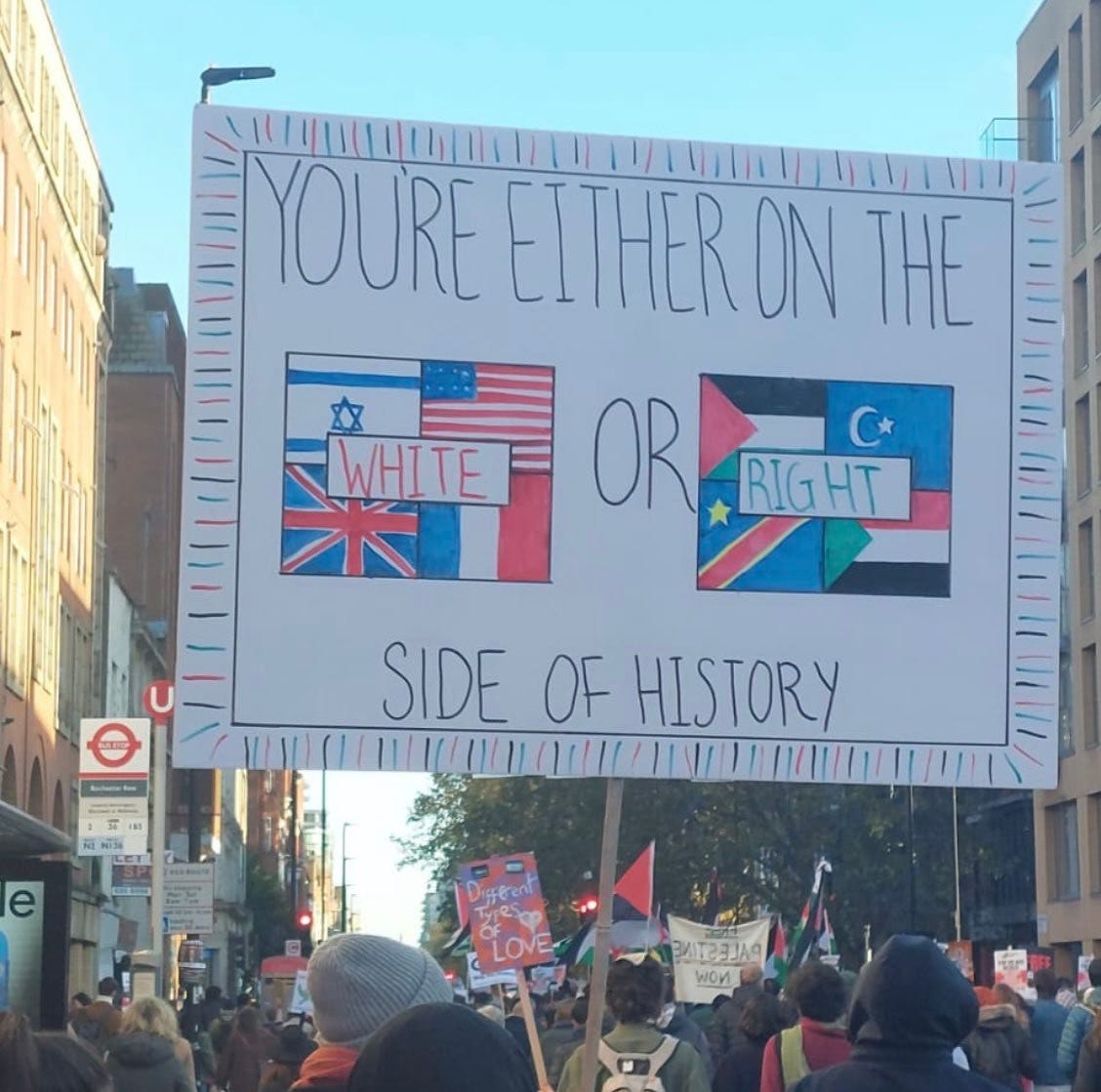

After Hamazis gleefully killed a stack of Jews—one of the largest terrorist killings ever; per capita, the most murderous terror killing ever; the largest slaughter of Jews since the Holocaust—within hours, various academics told us how it exemplified decolonisation.

When you look into the history, this turns out to be literally true.

The “lesson” of decolonisation was that if you terrorise settlers—if you kill entire families—they leave. You terrorise French settlers in Algeria, they leave. You terrorise English settlers in Kenya, they leave.

So, the logic of “decolonisation” goes, if you terrorise Jewish “settlers” in Israel-Palestine, they will leave. The PLO was founded in 1964 on the model of Algeria’s FLN and adopted the FLN’s “terrorise the settler” tactics, repeating local patterns that stretched back to 1920.

The logic behind such terror has now been tried for over a century in Israel-Palestine and it never works. The Jews of Israel are overwhelmingly refugees or their descendants, rather than settlers. They have no France or England, no “home country”, to go back to. They react to such terror acts as people with nowhere else to go.

So, how can folk not see the difference? Historically, local Muslims were often blind to the difference: Russian-speaking Jews were Russians, German-speaking Jews were Germans. They were all Franj, or possibly Rum. All kaffir. This blindness became far more wilful as Jewish refugees from Muslim lands flooded into Israel. Postcolonial commentators in the West share a similar blindness.

Another large reason, however, is an outgrowth of Postcolonial Theory, which classes Israeli Jews as “settlers”: they cannot be refugee populations. And at this point, the circle closes. Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth is the ur-text of Postcolonial Theory. The book was written while Fanon was resident in Algeria during the Algerian Revolution. He was an avid supporter.

That The Wretched of the Earth is the ur-text of Postcolonial Theory says very bad things about both Postcolonial Theory and academe. The Wretched of the Earth is mostly an angry rant that mistakes Theory for evidence and treats historical events as a pick ‘n’ mix to feed its narrative. This narrative is not over-burdened with consistency as various groups play whatever rhetorical role suits Fanon in different bits of the book.

Tossing around some Freudian—and rather more Marxist—terminology does not make a series of assertions analysis. It’s entirely in intellectual character that Postcolonial “theorists” now can’t—or won’t—tell the difference between settler colonialism and a state largely founded and populated by refugees.

Fanon’s use of Marxist terms also undercuts the moral pretensions in his book. What is a Marxist? Someone for whom no amount of mass murder and tyranny will stop him worshipping the splendour in his head. No one can top Marxist regimes for dehumanising, murderous tyranny and exploitive domination. Using Marxist terminology and aspirations to critique colonialism—as if that confers some moral power on the criticism—is a sick joke.

Instead, let’s start—as one should—with some actual history, not the caricature and cartoon history we’re served in The Wretched of the Earth.

Recurring imperialism and settlement

Fanon was born in Martinique and served with Free French forces in the Caribbean and in Europe. Fanon’s only other connection to the Algeria—apart from being a resident during its (1954-1962) war of independence from France—was that it was also part of the French Empire. Fanon himself was a Francophone intellectual.

The Maghreb has been subject to various waves of invasion and settlement over millennia. Those amazing seafarers and traders, the Phoenicians, established the city of Carthage, which dominated the region until its conquest and destruction by the Roman Republic.

The region was then subject to Roman rule and settlement. Centuries later, Roman rule was displaced by the conquering and settling Vandals. Their rule was in turn overthrown by the Eastern Romans (“Byzantines”). That in turn was replaced by the armies of the Rashidun Caliphate and Umayyad Caliphate and Arab settlement.

Various Muslim dynasties then ruled various parts of the Maghreb, the ebb and flow of which enabled a scholar like ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) to develop his analysis of historical patterns. (An analysis so powerful, it applies to the rise and fall of the Soviet Union.)

In 1830, the Kingdom of France invaded and—as had been the recurring pattern with imperial conquest in the region for over two millennia—settlement followed. Just as the Berbers (Amizaghs) had put up centuries of armed resistance to Arab invasion and settlement, there was recurring armed resistance to French rule and settlement that culminated in the (ultimately successful) Algerian revolt of 1954-1962.

One of the rhetorical games Fanon plays is to class all non-imperial residents as natives. This creates a generic indigenous identity that utterly obscures such historical complexity. The only difference between the C19th and C20th French and the C7th and C8th Arabs is that the Arabs made their cultural, religious, institutional and settlement stick. The French did not. This is a salutary reminder that religion can prove to be more enduring than technological superiority.

Analysis failure

These long-running patterns of conquest and settlement had nothing to do with “capitalism”, European ethnicity, Enlightenment rationalism, or the melanin content of people’s skin. If you think any of these things are the most salient feature of a particular instance of this imperial-conquest-and-settlement pattern, your “history” is nonsense. If you ignore that there is a recurring pattern that pre-dates European colonialism by a millennia or two, then you can play misleading rhetorical games.

Progressives are perennially prone to recurring failure of analysis when it comes to imperialism by refusing to see it for what it is: a state phenomenon. Progressive policy claims rest on the notion that handing things to the state is how good things are achieved. If imperialism is inherently a state activity (as it is), then the state becomes much more problematic as an instrument for social progress.

The metropole of every single modern maritime empire became richer after losing its empire. Imperialism regularly parades itself as an instrument of national glory and wealth. Imperial state apparats seek to mobilise various interest groups—for instance, religious evangelism—to support and justify their expansion of territorial control. Imperialism remains, however, a state activity, in the service of the state apparat itself—including the ruler or rulers on top.

Sometimes, licensed (or not so licensed) adventurers may lead imperial expansion. The Spanish conquistadors and the various overseas corporations—most famously the British and Dutch East India Companies—operated this way. Imperial expansion from the periphery was a persistent pattern. Imperialism of this type only “stuck” when incorporated within an imperial state structure, sometimes via some franchise arrangement.

The reason why postwar decolonisation proceeded as it did is that nowhere enough folk back in various imperial metropoles had enough of a stake in continuing with empire. Imperial states were regularly defeated in independence wars—despite their technological and resource superiority—as it wasn’t worth it to metropole electorates to commit resources to maintain imperial rule.

Thus, the Attlee Labour government was very willing to grant India its independence because its voter base derived no benefit from British rule in India. India is a very prominent example of peaceful decolonisation, at least between coloniser and colonised. The violence involved in Indian and Pakistani independence was due to local strife. Fanon ignores the British withdrawal from India because it does not fit his moral Manichaeism.

Framing failure

Most “serious analysis” in Fanon comes from scattering Freudian and (particularly) Marxist terms through his molten prose. Social, commercial, economic and political action are regularly conflated as manifestations of “capitalism” or “colonialism”.

Neither Freudian nor Marxist theory is up for the use Fanon wants to make of it. Much of the Marxist terminology is simply embarrassing, forcing framings on events and societies that simply do not work.

The Wretched of the Earth is an example of how Theory can work as a substitute for evidence, which explains some of its enduring appeal, particularly to the innumerate.

The work is also another example of why “capitalism” is a worse-than-useless analytical term. It enables the elision of state activity in imperialism and creating class structures. In the case of imperialism, again and again, commerce and settlement followed in the wake of a conquering or acquiring state. Settlement was a mechanism for entrenching imperial control, not its original purpose.

Commerce is not predicated on owning “capital”, as Fanon apparently thinks. People who don’t use much capital or who use other people’s capital engage in a great deal of commerce. Calling an entrepreneur a “capitalist” misleads and leads to “put together the factors of production and crank the handle” notions of economic growth and foreign aid.

To be in commerce is to engage in discovery, coordination, and risk management. Sure, financing and use of the factors of production are both important, but the term capitalist obscures rather than reveals the nature of commerce.

Fanon is critical of what he calls the national bourgeoisie of postcolonial states, who he regards as parasitic and useless.1 He conflates the professions with commerce, elevates the political—the most dysfunctional element in such societies—while also acknowledging that state activity has often been highly exploitive.

In true Marxist style, however, he sees this last as an aspect of class dynamics. The state will be fine if run by correct folk with correct consciousness. That social progress comes from correct enlightenment is a recurring theme. One can see why Fanon appeals to the collective narcissism of academics. He licenses them to worship the splendour in their heads and assert a sense of moral superiority over everyone else in their societies.2

Rhetorical power

So, if Fanon’s history is cherry-picked to uselessness, and his analytical framings are meaningless, with what is one left? Molten prose that feeds a Manichaean world view. Wretched has mythic—not analytic—power.

Fanon in Algeria was neither French nor Algerian. Fanon was Afro-Caribbean, so a descendant of slaves whose ancestors were almost certainly enslaved by fellow Africans. Due to its geography, Africa was a continent where labour was perennially scarcer—and so more valuable—than land. Hence Africa was for millennia a continent of enslavement. This fed into the Islamic and Atlantic slave trades.

Fanon’s identification with Arab Algeria—Berbers/Amazigh are notably absent from his commentary—is an identification with an imperial, settler, enslaving culture by an ancestrally displaced descendant of slaves. This culture was still an enslaving culture at the time of the French conquest.

In colloquial Arabic, the term for Sub-Saharan Africans is abd—creature or slave. Whether the French-speaking Fanon was aware is unclear.

This culture and civilisation pioneered anti-black racism precisely because it was a morally universalist enslaving culture—so had to find excuses for enslaving fellow children of Allah. For instance:

The rest of this tabaqat [category], which showed no interest in science, resembles animals more than human beings …

Also in this category are those who live close to the equinoctial line [equator] and behind it to the end of the populated world to the south. Because the sun remains close to their head for long periods, their air and their climate have become hot: they are of hot temperament and fiery behaviour. Their color turned black and their hair turned kinky. As a result, they lost the value of patience and firmness of perception. They were overcome by foolishness and ignorance. These are the people of Sudan who inhabit the far reaches of Ethiopia, the Nubians, the Zinj and others.

Said al-Andalusi, Ṭabaqāt al-‘Umam [Categories of Nations], Chapter 3.

This categorisation as brutish is a recurring trope in Islamic thought. Here’s Ibn Khaldun three centuries later:

The inhabitants of the zones that are far from temperate, such as the first, second, sixth, and seventh zones, are also farther removed from being temperate in all their conditions. Their buildings are of clay and reeds. Their foodstuffs are durra and herbs. Their clothing is the leaves of trees, which they sew together to cover themselves, or animal skins. Most of them go naked. ... Their qualities of character, moreover, are close to those of dumb animals. It has even been reported that most of the Negroes of the first zone dwell in caves and thickets, eat herbs, live in savage isolation and do not congregate, and eat each other. … The reason for this is that their remoteness from being temperate produces in them a disposition and character similar to those of the dumb animals, and they become correspondingly remote from humanity. … All their conditions are remote from those of human beings and close to those of wild animals.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah, Third Prefatory Discussion.

Fanon replaced history with myth at both the narrative and personal level. Marxism is useful for this: The Wretched of the Earth shows how framing events to suit ideological, emotional and social leverage works. But as serious social analysis, it’s portentous failure.

In Wretched we are treated to generic peasants, generic colonialists, generic settlers, generic trade unionists, standard patterns of nationalists, national feeling as unproblematic for most of the narrative, with specific events plucked out to support the narrative. This then shifts to more specific groupings, and even criticises things previously extolled, as its suits his rhetoric. All social action is then subsumed into the colonialism-and-resistance narrative. It becomes a universal prism. Nothing else has to be learnt or applied.

Fanon universalises general armed struggle as colonialism’s default pattern, when successful pacification was very common—this is what states do, whether empires or not. Colonial authorities defeating a local uprising and then handing power over peacefully happened more than once. Malaysia and Kenya were both examples.

One of the analytical flaws of The Wretched of the Earth’s generic analysis is that Fanon takes French colonialism to be the default: for instance, in its treatment of traditional chiefs. British colonial authorities tended to be more willing to work with local authorities than were more secularist and rationalist French colonial authorities. Fanon does refer to events within the British Empire—the Mau-Mau rebellion for example—but it does not inform his wider analysis.

Fanon also attributes patterns of state control to colonialism that are general patterns of state rule. Peasant revolts, for instance, are a hardy perennial in farming polities.

Fanon himself was a product and a denizen of the Francophone world. He is, understandably, enraged at a Francophone civilisation that made to include him, paraded its universalist values, and then repeatedly reminded him that he was “black”.

Racialisation was a product of imperialism, colonialism and cross-continental slavery in civilisations with claims to moral universalism: if everyone is equal before God, then enslaving fellow children of God has to be justified in some way or another. This is why racism has been in such serious decline in post-imperial Western countries. That is, until Post-Enlightenment Progressivism (“wokery”) revived the racialisation of identity for standard favour-divide-and-dominate reasons.

Postcolonial Theory has encouraged and mobilised this racialisation through its decolonisation narratives. They draw on Fanon’s moral Manichaeanism, making colonialism the only operative moral fact about European civilisation and culture—as if it contains no manifestation of human achievement.

This nonsense builds on a refusal to see imperialism as overwhelmingly a state activity and unwillingness to note its normality throughout history. The achievements of Western civilisation are real, and have little to do with either imperialism or colonialism. This is how landlocked and empire-free Switzerland became richer than Portugal, despite the latter engaging in serious colonialism for centuries.

Fanon repeats the nonsense claim that European wealth came about thanks to imperial exploitation. First, this is simply not true. The Imperial metropoles got richer after they lost their maritime empires. Secondly, European productive, technological and organisational capacity was how they were able to be imperial in the first place.

The reality is that Europeans were able to conquer most of the planet with relatively minor expeditionary forces precisely thanks to the depth of their (home-grown) institutional, technological and organisational superiority. Often, the biggest military difficulty even outside Europe was other European forces: American settlers, Boer farmers, rival European imperial forces. Even today, Western armies dominate conventional warfare.

Fanon also has a patchy sense of how things work. By default, he reduces social complexities and historical events to a Manichaean power dynamic, with oppression the only salient moral fact. The role of the British Empire in abolishing slavery—like Israeli Jews as descendants of refugee populations—has nowhere to fit.

Fanon’s analysis requires no numeracy, no field work, no grappling with the complexities of constraints and trade-offs, nor even inconvenient consistency. It requires only mastery of Theory: rhetoric and narratives that impart to its initiates a gratifying moral grandeur. The world’s problems are solved by having the right critical consciousness. The work is full of bad history, bad anthropology, and cookie-cutter economics held together by deracinated rage.

Fanon writes, in what was become a dictum of modern schooling:

The level of consciousness of young people must be raised: they need enlightenment.

No, they need to be provided with an education, not grandiose indoctrination of the Postcolonial variety.

Myth is not reality

The Wretched of the Earth is a powerful statement of mythic rage. But mythos is not logos. Myth is not reality. That such myth-making has become a founding text of Postcolonial Theory—a book that uses Theory as a substitute for evidence—expresses so much of what is wrong with Decolonising-the-[fill in the blank] activism.

Postcolonial Theory exemplifies why activist scholarship is degraded scholarship. Understanding is sacrificed in favour of creating motivating myths. These myths are now used to fuel and excuse Jew-hatred.

The Iranian ex-Muslim who argued that comparing Muslim indifference to Muslim suffering elsewhere with Muslim obsession over Israel shows that Palestinian sloganeering is really cover for Jew-hatred has a point. But there’s more to the story. There’s also Postcolonial Theory—with its “settler colonialism” rhetoric. It’s ur-text is Fanon’s mythic rhetoric of rage. Hamas even rewrote its Charter (in 2017) to bring it into line with decolonial ideas.

When various supporters of decolonisation claimed that the Hamazi attacks of October 7 were decolonisation, they were correct. There’s a direct line from terrorising settlers in Algeria to terrorising Israelis. Yet Postcolonial Theory is so analytically and morally bankrupt that it cannot parse the difference between colonial settlers—who could retreat back to a metropole where they were still citizens—and a country full of refugees and their descendants who have nowhere else to go.

The Wretched of the Earth, with its dehumanising Manichaean moral binary, is a terror manual. The vile simplicities Fanon expressed continue to generate and excuse horror.

I admit struggling through The Wretched of the Earth. I did not learn anything beyond one man’s obsessions. This work has no place in the academy except as a study in myth-making and rhetoric. It’s not a work of moral righteousness, but a grandiose, overwritten substitute for one.

References

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Penguin, [1961] 1967.

Robert Neuwirth, The Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Pantheon Books, 2011.

Unlike European bourgeoisies, which he regards as creative—until he gets to his anti-Europe rant of a conclusion, when they become exemplars of a monstrous, inhuman, dead-end civilisation.

The post-French FLN regime disrupted traditional Algerian culture—particularly traditional Sufi religious culture—far more than the French managed. This then created a religious-institutional vacuum into which a virulent Islamawi, Islamism, moved, with brutal and disastrous consequences.

Given a legal consultant's work is never done, a short comment to let you all know that I'll be leaving for the US today for work. Presence around here--at least on my part--will be light to variable for the next week or so.

An interesting essay...agree with all of it. I would just make this observation though: In my view, most white-liberal Correct-Think does not primarily derive from any deep ideological stance. It is shallower than that. The 'causes' - 'oppression', 'colonialism', 'racism', 'sexism' et al - are, to the white-liberal, just shallow abstractions. The real driver is "the endless struggle to think well of themselves" (as TS Eliot put it). https://grahamcunningham.substack.com/p/are-we-making-progress