The Progressive Revolt Against Equality: I

Understanding Dialectical Faith

This is the forty-second piece in Lorenzo Warby’s series of essays on the strange and disorienting times in which we live.

This article can be adumbrated thusly: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs,” is how ants and other eusocial insects behave in service to the lineage of a nest or hive. Humans can only act like that within families or small groups with deep connections. All attempts to do so compulsorily and at scale have been horrible disasters, as Homo sapiens are not ants.

The publication schedule and links to all Lorenzo’s essays are available here.

Housekeeping: apologies for delays and sporadic publication. Normally I’m the one called away to do consulting, but this time Lorenzo has been on the receiving end of a consultancy gig. He’s not been able to respond as much to comments as he’d like on here, or edit his own (future) pieces in response to observations from subscribers.

That said, the Easter long weekend is coming up and he’ll be able to down tools at last.

Do remember, my Substack is free for everyone. Only contribute if you fancy. If you put your hands in your pocket, money goes into Lorenzo’s pocket.

Paid subscribers get access to exclusive Chatham House unrecorded streams with Lorenzo and me (we’ll do another one over Easter), as well as pre-recorded discussions and publication progress reports like this one.

Equity—Diversity Equity Inclusion (DEI)—is concerned with the just distribution of resources within society. In practice, any form of inequality in outcomes is considered presumptively unjust: indeed, as a marker of oppression. Action therefore needs to be taken to ensure shares are made equal.

This subordinates the difficulty in creating and maintaining a complex society to moral demands. In its full Critical Social Justice form—as we shall see—there are no problems of order that are not subordinated to the struggle against power, domination, oppression, and alienation.1

A fundamental feature of Post-Enlightenment Progressivism (“wokery”) is a concern for equality of outcome, but a very specific form of equality of outcome: equality of outcomes between and across identity groups, not between individuals. The existence of any variation in income, wealth, careers, etc. between identity groups is taken as presumptive evidence of some form of unjust deprivation—usually cast as oppression—such as structural racism.

“Wokery”, or Post-Enlightenment Progressivism, is the popularisation of Critical Theory. Critical Theory is a further iteration of the Dialectical Faith, whose first iteration was OG Marxism (aka “vulgar Marxism”).

The Dialectical Faith

We are the normative species because we evolved highly cooperative subsistence and reproductive strategies—using technology—so as to raise our biologically expensive children. We are the religious species, because becoming the language-using species at the level we have required self-consciousness to interrogate and assemble packages of information.

The oldest profession is not lady of negotiable affection, but shaman: a cultural specialist in managing self-consciousness (including of one’s own death), through myth, ritual, narrative and advice. It is from this role that both religions and wisdom traditions develop.

The Dialectical Faith—as developed by Marx, riffing off Feuerbach, Hegel, Schiller, Rousseau, perhaps Helvetius—sees humans as having a distinctive metaphysical role because we are self-conscious agents (i.e., are conscious subjects). We create society and society creates us, in a dialectical process. In the words of Marx:

We know only a single science, the science of history. One can look at history from two sides and divide it into the history of nature and the history of men. The two sides are, however, inseparable; the history of nature and the history of men are dependent on each other so long as men exist. The history of nature, called natural science, does not concern us here; but we will have to examine the history of men, since almost the whole ideology amounts either to a distorted conception of this history or to a complete abstraction from it.

We do not merely act in the world, we act in the world based on our conscious vision of what we seek to create. This means working for someone else is alienating: you are progressing their vision, not yours. The claim is that under primitive (tribal) communism, there was unity of theory and practice. There was no barrier between our vision and action. This unity was, however, restricted to each tribe.

Then, the Dialectical Faith says, division of labour developed, breaking our unity of thought and action. This enabled the development of property, enabling one person to exclude and dominate another, imposing their vision of rightful ordering on those who lacked such property, and commodifying the alienated products of labour.2

It is from here that the language of privilege (exclusion) is used to describe what is often more accurately seen as advantage: indeed, complex patterns of advantage and disadvantage.

Society, the Dialectical Faith historical narrative claims, has been going through various stages, each based on the form of property dominant in that technological era, generating contradictions that are dialectically resolved by the next stage. This is a process of decreasing incompleteness in the humanising of society by expanding becoming.

Eventually, capitalism will so expand our productive capacities—while immiserating the working masses due to the concentration of exclusory capital, leading to transformative revolution—that the administered society of socialism will be able to eliminate classes and exclusory property. The final, global, universal unity of theory and practice (i.e. communism) will thereby come to be.

As Marx says:

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things [Emphasis in original.]

Our productive capacity will be so great, that we will so humanise the world, that division of labour will end, for:

In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Indeed, with this achievement of the global unity of theory and practice:

Communism is the riddle of history solved, and it knows itself to be this solution.

Hence the possessors of the Dialectical (i.e. critical) consciousness have an epistemic authority denied all others.

The Dialectical Faith sees everything that matters as being socially constructed. This means that morality trumps order, as all constraints are signs of oppression. They are a sign of what is socially constructed failing to liberate our subjectivity as a fully humanised society would. The true apotheosis of human society and history is when all those constraints that produce divisions of labour and dominating, exclusory property are eliminated.

This is the worship of the splendour in one’s head—the grounding of judgement in the imagined future—at its most complete. If one does the work (i.e. engages in praxis) to spread the Faith—operationalised by the latest iteration of Theory—unity of theory and practice can be achieved via social transformation.

The Dialectical Faith has generated various spin-offs. The first is that developed by Marx himself: conventional or “vulgar” Marxism where the crucial drivers are economic forces—bourgeois, proletariat, capitalism. The next spin-off is Lenin operationalising Marxism by—as he explicitly says—Jacobinising it: grafting onto it centrally organised politics unlimited in scope and in means.

In reaction to the failure of proletarian revolutions to occur in advanced “capitalist” countries even under the shock of the 1914-1918 Great War, Georg Lukacs and Antonio Gramsci developed cultural Marxism. As Gramsci wrote:

Socialism is precisely the religion that must overwhelm Christianity. … In the new order, Socialism will triumph by first capturing the culture via infiltration of schools, universities, churches and the media by transforming the consciousness of society.

Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse developed Critical Theory in response to the same failure of proletarian revolution to erupt,3 riffing off Marx’s famous comment:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.

The metaphysical significance given to human subjectivity has been extended in the subsequent operationalisations of the Dialectical Faith. Any significant constraints on one’s subjectivity become oppression. This is why the thought of various post-structuralist and post-modern French theorists—with their deep scepticism about structure, their centring of the social relationship of power, and elevation of words and language as self-referential systems—was able to feed into new iterations of the Dialectical Faith.

It’s also why Trans resonated so strongly: bringing the body, and how we conceive of it, in alignment with Trans subjectivity fits the model at the core of the Dialectical Faith. As everything is wounded by its not-yet-fully humanised incompleteness, the axiom of Critical Race Theory—that the question is not whether racism exists, but how it manifests in specific circumstances—also fits right in.

The most recent spin-offs—built on merging Critical Theory with Foucault and other French Theorists—include Critical Race Theory, Queer Theory, Critical Pedagogy and Intersectionality. These outgrowths of the Dialectical Faith can be lumped together as Critical Social Justice. The imposition of compulsory Theory courses in universities—from the 1990s onwards—has helped spread and entrench the Dialectical Faith in academe.

In the original Marxist model there are the bourgeois who possess capital creating the system of capitalism within which the proletariat are alienated and exploited.

In the realm of sex, there are men who possess masculinity creating the system of patriarchy within which women are alienated and exploited. In the realm of race, there are whites who possess whiteness creating the system of white supremacy within which people of colour are alienated and exploited. In the realm of sexuality, there are normal people who possess normalcy creating the system of cis-heteronormativity within which the queer are alienated and exploited. In the realm of education, there are the literate who possess literacy creating the system of power-knowledge within which the illiterate are alienated and exploited.4

All this can be tied together using intersectionality. Oppressor groups possess privilege that excludes and oppresses the marginalised and minoritised. The language of verbalised nouns—minoritised, marginalised, dehoused, undocumented, and so on—all comes from the Dialectical Faith holding that these are all failures to create a fully humanised world. All problems of order are subordinated to the struggle against power, domination, oppression and alienation.

While operationalising the Dialectical Faith is subject to error correction—hence the various spin-offs have evolved through selection processes so as to spread through institutions—the Faith itself is not subject to error correction. This is a problem, as it’s bonkers nonsense.

First, we are a sexually reproducing species, which leads to a division of labour at the biological level. Second, foragers do not display anything remotely like the unity of theory and practice Marx postulates. Their behaviour is conventionally human. Marx expounds yet another version of the noble savage myth.5

Third, division of labour, like commodification, is required to do any resource-using activity at scale. Our productive capacity’s development goes hand in hand with expansion of division of labour and of commodification. Since there’s evidence of exchange and gift transfer networks from the beginnings of our evolution as a species, we are probably adapted to commodification by now.

Fourth, things are only socially constructed within limits set by the underlying structures of the universe. Physical reality, and our own biology, imposes a whole set of constraints to be navigated. This means there are no complete solutions, just various trade-offs—such as the paradox of politics.6

Seeing everything as fatally incomplete—hence the ruthless criticism of all that exists—provides a basis for criticising every trade-off. That means criticising everything that actually works.

What the Dialectical Faith provides is coordinated motivation—including, as James Lindsay says, spiritual answers for resentful people—with an endlessly adaptable template dividing society into oppressed and oppressors. The Dialectical Faith, with its elevation of human subjectivity and transformative social action, is an intense version of progressive cognitive-based identity, built around the splendours in one’s head.

Believers get to sneer at—and denigrate as cognitively, morally and psychologically inadequate—all who do not embrace the Faith. This takes in all human striving across the millennia that does not suit the Faith. Theory grades evidence, so any small study, lived experience, or example that suits Theory can be adopted as support and all that does not suit castigated as manifestations of, or supports for, oppression.7

This leads to deep structural stupidity. If all disagreement with core claims show one’s moral and cognitive inadequacy, feedback and accountability are both fatally undermined. The spread of the Dialectical Faith has much to do with how we have increasingly become a civilisation of broken feedbacks.

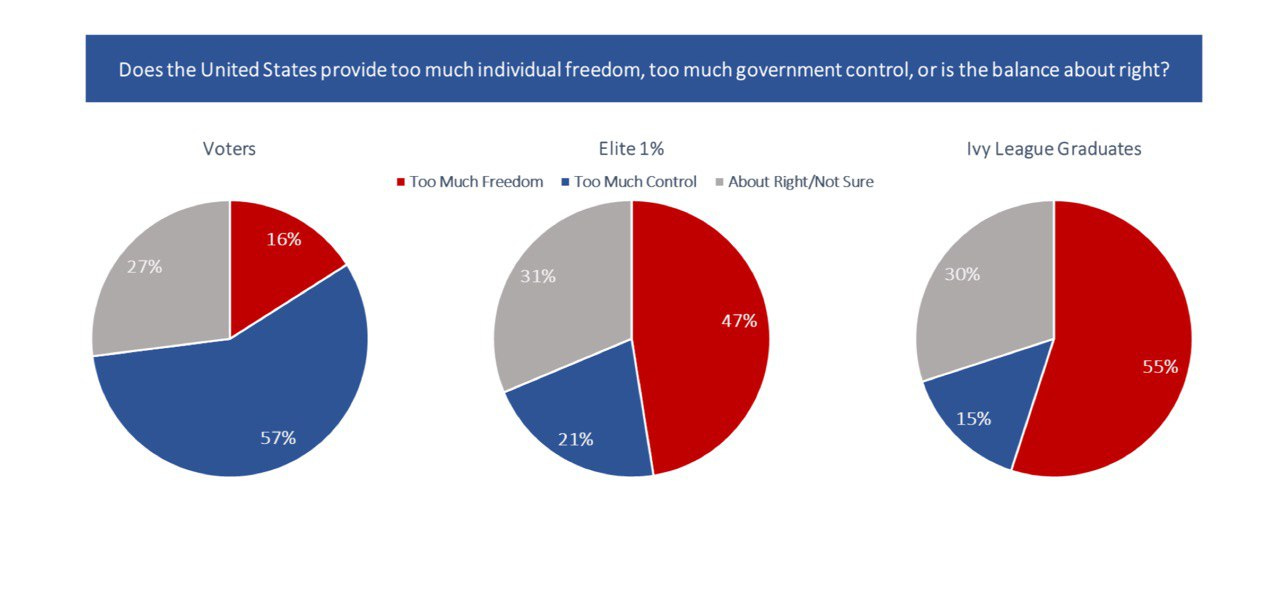

Mainstream media has become dysfunctional precisely because it has become dominated by graduates of elite universities who not only buy into various versions of such claims, but sell the notion of moral and cognitive superiority on the basis of conveying various narratives to their readers. This explains development of the pravda model of mainstream media.

Complications of equality

The streams of thought that descend from Marx have a complicated relationship with equality. From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs is not a principle of equality. First, ability and needs both vary. Second, there is a clear intention that resources be transferred, as a matter of right, not of choice. Indeed, humans are to be so changed that they just do this naturally.

In his Essay on Liberation, Herbert Marcuse holds that we humans have to be transformed at our very being, to create a biological basis for socialism. We have to be transformed so that we will automatically operate on the basis of from each according to his capacities, to each according to his needs.

Biologist E.O. Wilson’s quip—“good ideology, wrong species”—is therefore very apposite. From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs is how ants and other eusocial insects behave: at least in service to the lineage of the nest or hive. Humans can act like that within families or small groups with deep connections (such as kibbutzim). All attempts to do so compulsorily and at scale have been horrible disasters, as Homo sapiens are not ants. We are not a eusocial species, we are an ultra-social species.

We are the species that is better at non-kin cooperation—that is, cooperation across genetic lineages—than any other species on the planet, by orders of magnitude. The Christian Eurosphere—Europe and its descendant settler Neo-Europes—came to dominate the planet by evolving institutional structures that put our non-kin cooperation on steroids. This evolved from the Christian sanctification of the Roman synthesis: law is human (so not based on revelation); single-spouse marriage with mutual consent (so partnership marriages);8 no cousin or other consanguineous marriage; testamentary rights (individual wills). This structure broke up clans and kin-groups in the manorial core of Europe.9

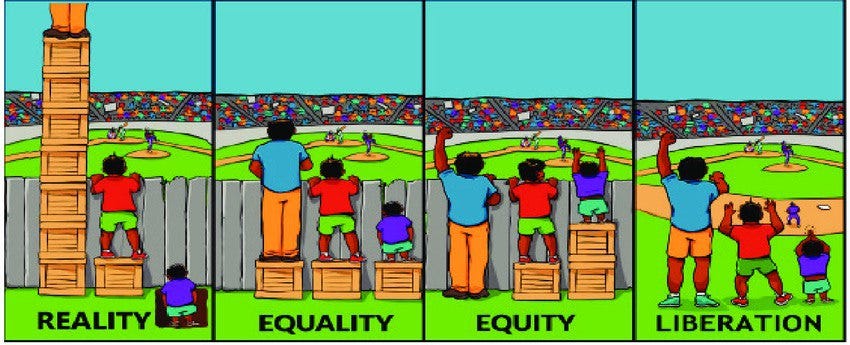

The last frame in the cartoon above depicts a liberatory future based on a freeing from constraints—specifically, those of property. The problems of free riding, the tragedies of the commons, and other problems of collective action, are just wished away, even though almost all species are not social species precisely because of the power of those problems.

This, by the way, is what happens when the perimeter fence is removed or breached during major sporting fixtures.

While social species dominate the animal biomass of the planet, they are phylogenetically rare because collective action problems are so salient. All other species that manage social cooperation at scale do so by keeping it within the lineage. The neuter or female workers and soldiers of an ant, termite, wasp, or bee colony serve their mother’s lineage.

We Homo sapiens are the only species that can manage cooperation at scale across genetic lineages. We use language, norms, and institutions to do so. Even given that, what eusocial insects are genetically structured to do with hormones and pheromones is beyond our linguistic, cognitive, and normative capacities to do at the required scale for any society to be based on from each according to his capacities, to each according to his needs.

References

Books

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Roelof van den Broek and Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times, State University of New York Press, 1997.

Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, The Truth about Cinderella: A Darwinian View of Parental Love, Yale University Press, 1998.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Michael Mitterauer, Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path, (trans.) Gerard Chapple, University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2010.

Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, Harvard University Press, [1965] 1982.

Emmanuel Todd, Lineages of Modernity: A History of Humanity from the Stone Age to Homo Americanus, Polity, [2017] 2019.

Articles, papers, book chapters, podcasts

Jacobus J. Boomsma, ‘Lifetime monogamy and the evolution of eusociality,’ Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society B, (2009) 364, 3191–3207.

Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts R, Behrensmeyer AK, Deino AL, Leslie DE, Ambrose SH, Ferguson JR, d'Errico F, Zipkin AM, Whittaker S, Post J, Veatch EG, Foecke K, Clark JB, ‘Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age,’ Science. 2018 Apr 6; 360(6384): 90-94.

Chris D. Frith, ‘The role of metacognition in human social interactions,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2012, 367, 2213–2223.

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353.

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Polygamy, the Commodification of Women, and Underdevelopment,’ Social Science History (2021), 46(1):1-34.

Richard Sosis and Candace Alcorta, ‘Signaling, Solidarity, and the Sacred: The Evolution of Religious Behavior,’ Evolutionary Anthropology, 12:264–274 (2003).

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136.

M, Tomasello, ‘The ultra-social animal,’ European Journal of Social Psychology, 2014 Apr;44(3):187-194.

Robert Trivers, ‘Parental investment and sexual selection,’ in B. Campbell, Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, Aldine de Gruyter, 1972, 136–179.

J. Watanabe, J. and B. Smuts, ‘Explaining religion without explaining it away: Trust, truth, and the evolution of cooperation in Roy A. Rappaport’s “The Obvious Aspects of Ritual,” American Anthropologist, 1999, 101:98-112.

Rousseau and Marx, key figures in the development of this stream of thought, were both somewhat pathological in their personal resentment of various order constraints. These included civility, personal hygiene, care for one’s children, and working for a living.

The owners of such property collectively wield a demiurgic power that imprisons the rest of us in their social dominion: gnostic conspiratorialism. The Dialectical Faith offers—via critical consciousness—the special, Hermetic, knowledge that enables one to see, and break free of, that socially imprisoning demiurgic power.

This failure of the workers to act out the role their cognitive betters—those believers in the Dialectical Faith with a proper grasp of Theory—had assigned to them was the beginning of accelerating disillusion with the working class. It’s reached the point where “progressive” politics now reliably acts against the interests of the resident working class. The pretence that economic migrants are asylum seekers seeks to strip the working class of control over migration policy, for example. Such politics is openly contemptuous of working class concerns, and its moralising fig-leaves give cover to class prejudice.

James Lindsay has done sterling work teasing out how Marx’s underlying model has been recycled.

Rousseau viewed the indigenous folk of the Americas as having qualities that civilised man had lost—and that society needed to regain in a form that enabled the preservation of the achievements of civilisation. Schiller continued this line of thought.

We rely on the state to protect us from social predators but the state is the most dangerous of social predators.

As James Lindsay correctly notes, in terms of the Christian mythos, it is Satanic. It’s the serpent in the Garden of Eden seen as a light-bearer bringing liberating knowledge. God, meanwhile, is an imprisoning delusion, to be replaced by the creative power of a liberated humanity. This delusory nonsense makes the Dialectical Faith much nastier and more conceited than Christianity, hence its horrific consequences when in power. Many commentators have noted the astonishing cruelty of Dialectical Faith regimes. Cancel culture—and its virulent abuse of dissenters—also displays considerable cruelty.

Partnerships centred around care for their shared children so that wives could be—and typically were—managers of households and were left in charge when the husband was away. Polygynous societies divert elite women into mutual competition within a household over prospects for their children. Folktales warning of the dangers of stepparents occur across human societies. Other wives or concubines of an elite male are stepmothers to his children not their own—and harem politics can be notoriously vicious. Polygyny thus typically precluded leaving a wife in charge in the absence of the husband.

Kin-groups persisted in pastoralist areas (the Celtic fringe and the Balkans) until suppressed by state action. The political suppression of kin-groups—replacing identity-by-lineage with identity-by-location—extended back to the Classical Mediterranean. For instance, constitutional reforms in both Athens and Rome changed the definition of tribe from lineage to location (tribus is Latin for what we would call a constituency).

The long absence of kin groups from the core of what became Western civilisation has persistently led Western scholars to underestimate or miss their significance in other cultures. Daniel Pipes’s study of slave warriors in Islam is a classic example of failing to see the significance of kin groups. Slave warriors only became dominant in kin-group Islam after the Abbasids abolished the tribal confederacy model of the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates. The lineage confederacy polities of steppe Islam did not use slave warriors. Nor did non-kin-group Islam (notably Islander and Malay), as its rulers did not have to worry about kin-groups colonising their armed forces.

"The existence of any variation in income, wealth, careers, etc. between identity groups is taken as presumptive evidence of some form of unjust deprivation..."

This isn't quite right. Any variation favoring whites or males, relative to blacks or Hispanics, say, on such metrics is, of course, indisputable evidence of unjust structural privilege, but any variation favoring Jews, Asians, or women, say, relative to whites or men, is apparently no such thing. You'd be certain to be called a racist or misogynist for even mentioning this inconsistency, and be at serious risk of losing your job if you were foolish enough to broach the subject in many a professional setting. Among the problems with the Intersectional understanding of social reality is that it doesn't appeal to a consistent standard of evidence. Instead, it rests on a priori assumptions about who is privileged and who isn't. Since actual social reality is often quite different from what Intersectional Theory would predict, the theorists can only maintain the façade of credibility by threatening the livelihoods and reputations of those so impudent as to notice.

Outstanding article. Among many other things, it reminds me that the scaling effect, especially where socialism is concerned, is something I've been curious about for many years now.

Several different kinds of human social organizing structures can work (at least reasonably well) for groups of fewer than Dunbar's Number of 150 people or so. The kibbutzim are one well-known practical example. Another is BBSs and MUDs and other small online groups from the Modem Age of social networks, which were frequently very good at self-policing into enjoyable and productive small communities. Discord servers are a similar success story today... but then there are the big social networks. These massively inflated chat groups aren't as successful, often turning incredibly toxic. Why does this happen?

Like the bar Cheers, small groups seem to work because "everybody knows your name" -- reliable personal trust can be established that lowers the predicted cost of cooperation with others in the group. (Axelrod's "Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma" remains a fantastic resource for exploring how cooperation can emerge.)

When scaled up past 100, 150 or so participants, though, many social organizations break down from exploitation. It may be that the majority of social systems don't scale up well. But there are a few social structures that somehow do (mostly) work. Why? What makes the difference? What are the structural features that enable one social organizing system to be productive even with millions of participants, while another scales up so poorly that subterfuge, or moralizing abuse, or the gun (or some combination of all these) must be used to force people to participate in it?

Capitalism in particular (mostly) does work at scale. What are its distinctive norms and institutions that allow it to be so successful at filling in for the absence of personal trust among billions of people, where the distinctive structural features of socialism do not?

Fodder for a future article, maybe. :)