Where do we go from here?

Decay without renewal

This is the second of two pieces on our time of global policy decay. If you haven’t yet read the first one, please do so now and then come back here.

The previous post went through the rise and decline of redistributive postwar social democratic policy regimes, followed by the rise and decline of neoliberal policy regimes. The latter involved expanded use of market mechanisms.

This second post further explores issues arising from both systems, and those policy regimes’ interaction with blank slate delusions. We use Minnesota’s welfare-fraud revelations as a particularly florid example of policy decay.

Created order

While commerce operates within institutional frameworks, the existence of informal (including black) markets shows how ubiquitous conventions of property are because of how our cognition is structured. This means the conventions of property can and do re-emerge with startling vigour, even within the most oppressive command economies.

Marx’s claim that private property is alienating, is “self-estrangement from our species-being”, is hogwash. We create property—the acknowledgment of yours!—because we are such social beings, because we are much more social than our primate cousins. We do so even within the pseudo-ordered chaos of command economies, thereby making them more functional than they would otherwise be.

Many civilisations have had notions of proper harmony—see the Egyptian concept of maat, the Chinese concept of dao or the Mongol concept of tore. But they all realised that such harmony had to be actively worked for; that good order was fragile; that disruptive, chaotic (i.e. entropic) pressures always existed, both within and outwith humans.

The capacity for order does not guarantee its achievement—still less does it guarantee an order that is not predatory or parasitic.

It’s a notable delusion to think harmony is natural and can be achieved by stripping away the painfully erected ordering structures of human society; that a cultural heritage is inherently the enemy of flourishing social order, rather than its constructor. Human sociality became much more fluid and egalitarian—and far more capable of creating culture, of being up-scaled via cooperative mechanisms—than that of our primate cousins because we systematically murdered our hyper-aggressive outliers.

Character tests (or their absence) matter precisely because humans are so varied, albeit within identifiable ranges and patterns. A flourishing social order requires pervasive and continuous effort.

We can operate via expectations because we are all human: because we are of a single, shared species, we can have robust expectations about each other. Yet expectations provide no guarantees, not merely because we cannot predict new information, but because we vary.

We can have much more robust expectations about each other within shared cultures—within shared maps of meaning—than across them. And even the degree to which that is true depends on distance between cultures.

Social alchemy theory—the utterly false notion that if we strip away what is constraining-so-oppressive, true social harmony will emerge—comes from Critical Theory. Nevertheless, its pious hopes of harmony-through-stripping-away-the-blocks-to-our-underlying-sameness is a delusion to which blank slate liberal universalism offers weak resistance, and into which it can easily slide. This is especially so when an elite status strategy derived from Critical Theory is added to the mix.

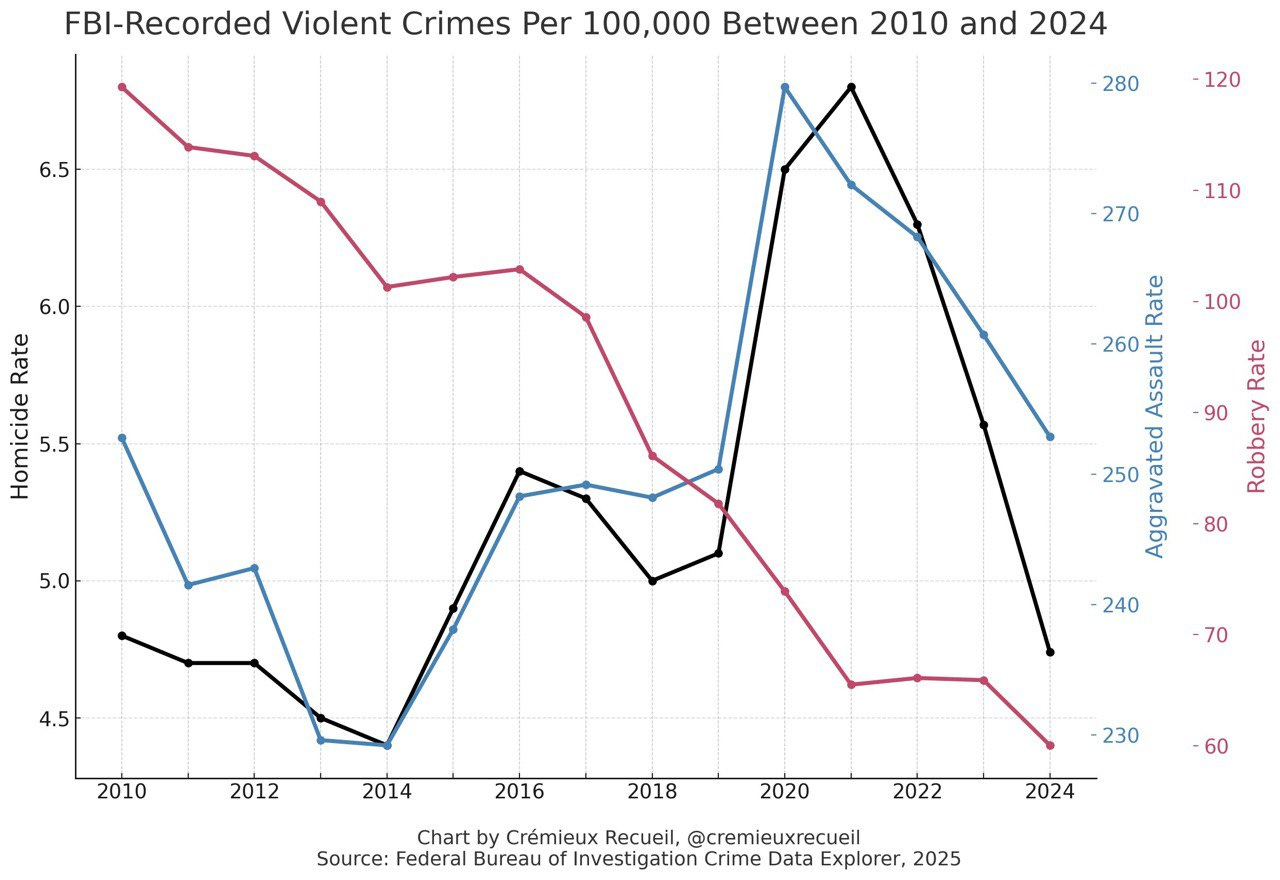

The propensity to look for “root causes” has blank slate roots. Such approaches shy away from considering how people vary in conscientiousness, aggressiveness, propensity to violence, patience, etc. All such variance entails grasping that we are not all basically-the-same blank slates, that we are evolved beings with the variation within our species that helps drives natural (and social) selection. Instead, people look for general social causes which—not coincidentally—elevate the authority and resource claims of those who can allegedly identify, and deal with, “root causes”.

The delusions of the free-floating universalism of liberal theory, especially when wrapped in Critical Theory status games, leads to a war against human particularism, against noticing—and even worse, championing—inconvenient-to-Theory differences. We have moved from a Lockean liberalism that was confident in freedom of speech and discourse to a Hobbesian hyper-liberalism that wants the leviathan surveillance state to impose a harmonious order on discourse.

The great hope of the blank slate is perfect human harmony because of our innate sameness. So, if we just strip away the accretions of difference—including our varied cultural heritages by “de-colonising” everything—harmony will be achieved.

This is delusory nonsense based on a false understanding of humans as a species, of how evolution works, of what being genetic and cultural beings entails, how one scales up human cooperation, how incentives and information interact, risk-management.

Blank slate universalism sees the particularism of culture as an enemy of social harmony even though such universalism is, itself, a product of a specific cultural matrix. Thus, philosopher John Gray wants the leviathan state to impose a levelling individualism without any sense that individualism itself is the creation of a particular cultural matrix.

Blank slate universalism does provide a form of rhetorical dominance, via commitment to imagined harmony. It also provides a program of action—suppress all the inconvenient accretions of difference by using any and all levers of power one can grab. There are status, authority, and power differences between those to be harmonised and those doing the harmonising.

Anti-discrimination/civil rights legislation creates networks of would-be harmonisers—in effect, workplace commissars, or perhaps inquisitors—paid and empowered to treat their fellow citizens as hovering on the edge of wrong-think (racism, etc.) and wrong-act (discrimination). They operate on the inquisitors’ principle that error has no rights and that they can reliably detect error. This has proved corrosive of freedom of thought, speech and association.

DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion)—often as part of ESG (Environmental and Social Governance)—has added training that regularly operates as little more than struggle sessions while producing a moralised “marginalisation” caste system—female over male, coloured over white, gay over straight, trans over cis, disabled over […]—which is corrosive of organisational harmony and function. Creating moral caste systems was very much a feature of DEI’s precursors—Mao’s Black and Red identities and North Korea’s Songbun system.

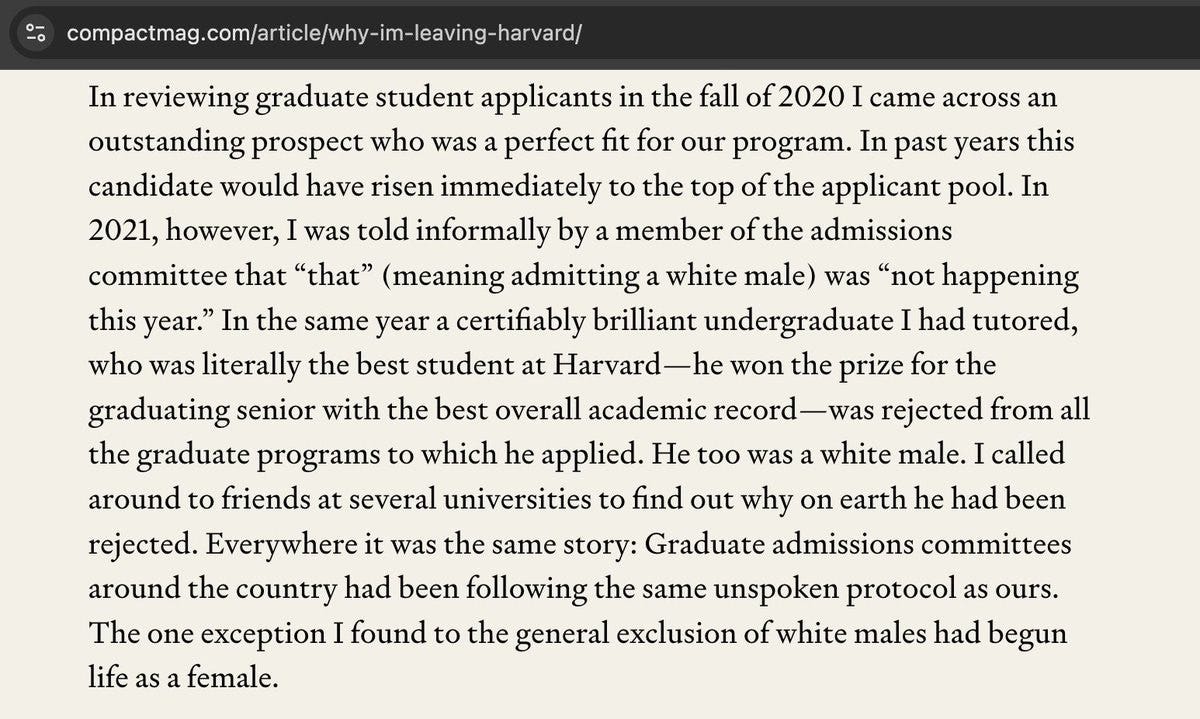

As straight white males are at the bottom of this moralised “marginalisation” caste system, the DEI mentality and commissariat has adversely affected the employment of young males of European descent (“white”), especially in entertainment, publishing and academe. The collapse in the quality of Hollywood’s offerings and box-office returns as a result has been notable—the US has thrown away a considerable amount of its “soft power”.

When contemporary Western elites look like mad utopians, it’s because—to the extent they’re operating on blank slate presumptions—they are. The blank slate is a Platonic vision of humanity, just as human rights law and international law are Platonic legal visions. These visions create Platonic guardians whose great moral understanding makes them moral shepherds and scolds for the rest of us.

International law academics tend to be particularly prone to Platonic Guardian arrogance. Striking moral poses is part of the field’s attraction. Public international law is not law—there are no remedies, beyond declarative statements—so international law academics’ pontifications are not subject to reliable and effective reality-tests. (A widespread problem within academe.)

Platonic views start with an abstract vision, typically highly moralised, and examine the world in their terms rather the world’s. In The Unity of Philosophical Experience, historian of Western philosophy Etienne Gilson writes:

Begotten in us by things themselves, concepts are born reformers that never lose touch with reality. Pure ideas, on the other hand, are born within the mind and from the mind, not as intellectual expressions of what is, but as models, or patterns, of what ought to be; hence they are born revolutionists. And this is the reason why Aristotle and Aristotelians write books on politics, whereas Plato and Platonists always write Utopias.

Platonic visions of humans as blank slates are both utopian—so give adherents a motivating sense of moral and rhetorical grandeur used to claim trumping authority over anyone who disagrees—and false, so delusional. This is a disastrous combination.

Shared delusions can be very powerful. Making shared false claims can aid social coordination. Being willing to engage in any level of rationalisation and not-noticing to affirm a shared false belief signals your commitment to motivating common claims as well as your soundness as a member of a moral in-group. This shifts the use of words from instruments of information and persuasion to signalling moral commitments and in-group soundness. For a particularly stark example of different use of words and moralised commitment to blank slate delusions see:

Cultural conundrums

One can see in neoliberalism implicit blank-slate presumptions. Everything is understood as a matter of incentives, of sticks and carrots. Get the incentive structure right, and all will be well. Show me the incentives—assumed in neoliberal Theory to operate identically across all human groups—and I will show you the outcome.

There’s no role in this for culture; no role for shared (or varied) maps of meaning; no role for underpinning norms; no concept of incentives depending on how one cognitively maps reality. This is an impoverished and delusional anthropology.

It’s clear where the neoliberal policy regime begins to run aground: on the rock of cultural differences and the ordering role of culture. It’s also clear where that will bite most strongly—mass immigration. This explains the rise of national populism.

Whether it is immigration policy, housing policy, energy policy, policing, or cultural politics (such as the debauching of beloved entertainment franchises), Western elites have systematically treated working-class concerns with contempt. (See, for instance, discussion of “toxic fans”.) For such elites, any robust sense of social solidarity and heritage is inconvenient, and probably fascist.

Much of this operationalised contempt has been via elite status games based on the normative dominance of blank slate delusions. But against whom are elite status games to be played? A country’s own working class, of course. This is why the 1991 Soviet collapse is such crucial break. The evaporation of any external existential geopolitical threat to the developed democracies made Western elites far less concerned about alienating their own working classes.

The attempt—via critiques of the postwar “open society” consensus—to re-litigate the Second World War is both fundamentally mistaken about when the key break point was and lets loose some deeply obnoxious ideas. “Weimar problems require Weimar solutions” has to be a serious contender for the stupidest political meme ever. A “solution” that leaves your country bombed flat, occupied by foreign powers, with 20 per cent less territory, and perpetrating a level of mass murder rivalled only by Communist regimes, is a much worse “solution” than the original problem.1

The toxic zealotry based on blank slate delusions that has pervaded universities, mainstream media, entertainment, arts and literature has involved a systematic attack on, and rejection of, the received cultural heritage of Western societies. This amounts to a criminal attack on the sustaining cognitive resources of our societies, and is one that actively sabotages learning.

Worse, such zealotry looks to politics to provide meaning; to provide a sense of purpose and moral validation; to generate maps of meaning—the architecture of belief. This is politics as substitute religion, as secular religion. Hence it replicates patterns that both rhyme with patterns from the Wars of Religion and also represent rejection of all the painful learning from those wars about not engaging in heresy hunting.

Cancel culture is about punishing people for words and ideas: heresy hunting and reputational witch-burning. It’s about blocking debate—and so social feedback—by enforcing a conformist self-righteousness. The leaders of Europe’s historical confessional states would like a word.

More to social life than efficiency

A pervasive difficulty for the neoliberal policy regime is that societies are not just places for free-floating transactions and efficiency is not the only criterion for public policy, human flourishing, or a successful society. Yes, the ubiquity of the pervasive conventions of property—and the power of the loss-gain-risk patterns of commerce—do enable robust predictions of general tendencies in human behaviour.

The problem comes from over-estimating the reach of those tendencies and/or over-rating efficiency. We do not only transact, we also connect. Societies and social orders do not only require efficiency, they also require resilience—the ability to operate across changes in circumstances over time. Most risk-management is about resilience, not efficiency. One of the problems with financialisation—of ever more use of debt, so promises-as-assets—is that it increases vulnerability to sudden information shifts.

If we look beyond efficiency and commerce, the claim that we produce in order to consume also becomes less impressive. We produce for all sorts of reasons beyond consumption: to have or express status; to generate leverage; as hedges against risks and uncertainty.

Off-shoring supply chains willy-nilly because efficiency is all that counts is a bad social strategy—it is all efficiency, no resilience. It is even less impressive if it allows others to maximise leverage over you. It is also less impressive if increased ability to consume for one group is bought at the expense of another group: that is, their ability to earn income has fallen more than consumption has become cheaper.

The China shock was real and grounded in Chinese Communist Party (CCP) policies. It was not driven by commercial motives, but sought mechanisms to maximise its leverage, both internally and externally. This included being willing to engage in remarkable levels of environmental degradation to do so (much of which it has outsourced).

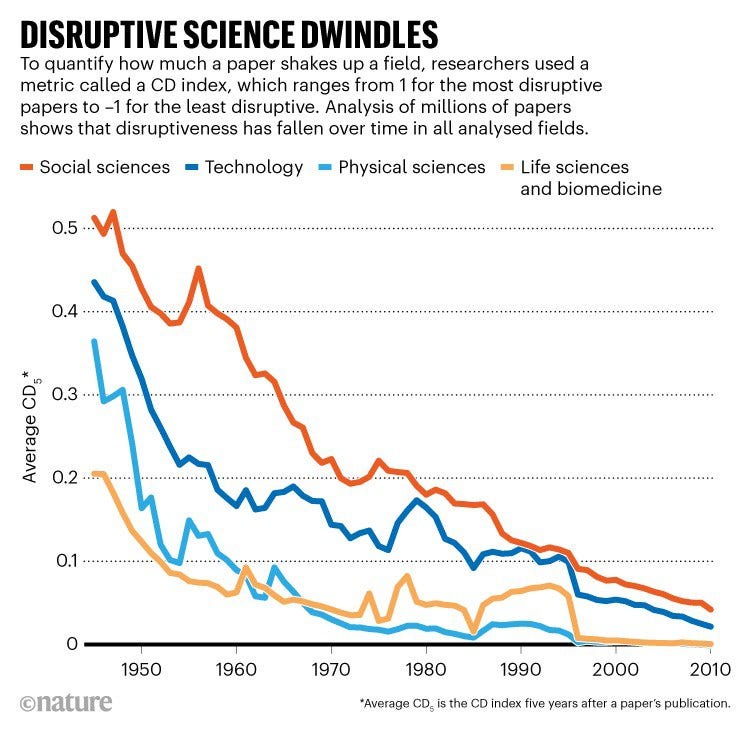

The CCP has even found a way to marry genuine technological innovation with failures of economic calculation, creating economically ineffective innovation, to the Chinese people’s detriment. Meanwhile, if one wants to see toxic innovation in operation, look no further than Western universities, where research grants based on cargo-cult worship of “knowledge innovation”—unconnected to any reality-tests that genuinely select for added value—has generated florid growth in toxic nonsense. The infamous feminist glaciology paper is a relatively mild example.

Our attempt to bureaucratise the scientific revolution has been a failure. Process does not guarantee value.

If we consider more than just efficiency in maximising production, free trade is not without its costs and dangers. It’s also much less important for mass prosperity than cheap, reliable energy. The US achieved unprecedented mass prosperity under a protectionist trade policy, although expanding internal markets on that scale reduces the costs of trade protection.

Just as the social democratic policy regime of 1945-1973 broke down in the stagflation of the 1970s and a flattening of productivity growth, so the post-1979 neoliberal policy regime is breaking down under the pressures of immigration, globalisation, bureaucratisation, feminisation of discourse and institutions, and collapsing fertility, with mass immigration failures providing the key sticking point. We are again witnessing a policy regime run out of puff as something developed to solve a previous set of problems confronts problems for which it lacks useful tools.

Cultural conundrums

Even in terms of maximising gains-from-trade transactions, immigration can increase transaction frictions. Cultural diversity makes social coordination harder and increases points of potential social friction, including competition for positional goods. Particularly when matched with DEI, immigration can actively discourage hiring and training locals. Tech entrepreneur Marc Andreessen says the quiet part out loud: US corporate employers import Africans so they do not have to hire African-Americans.

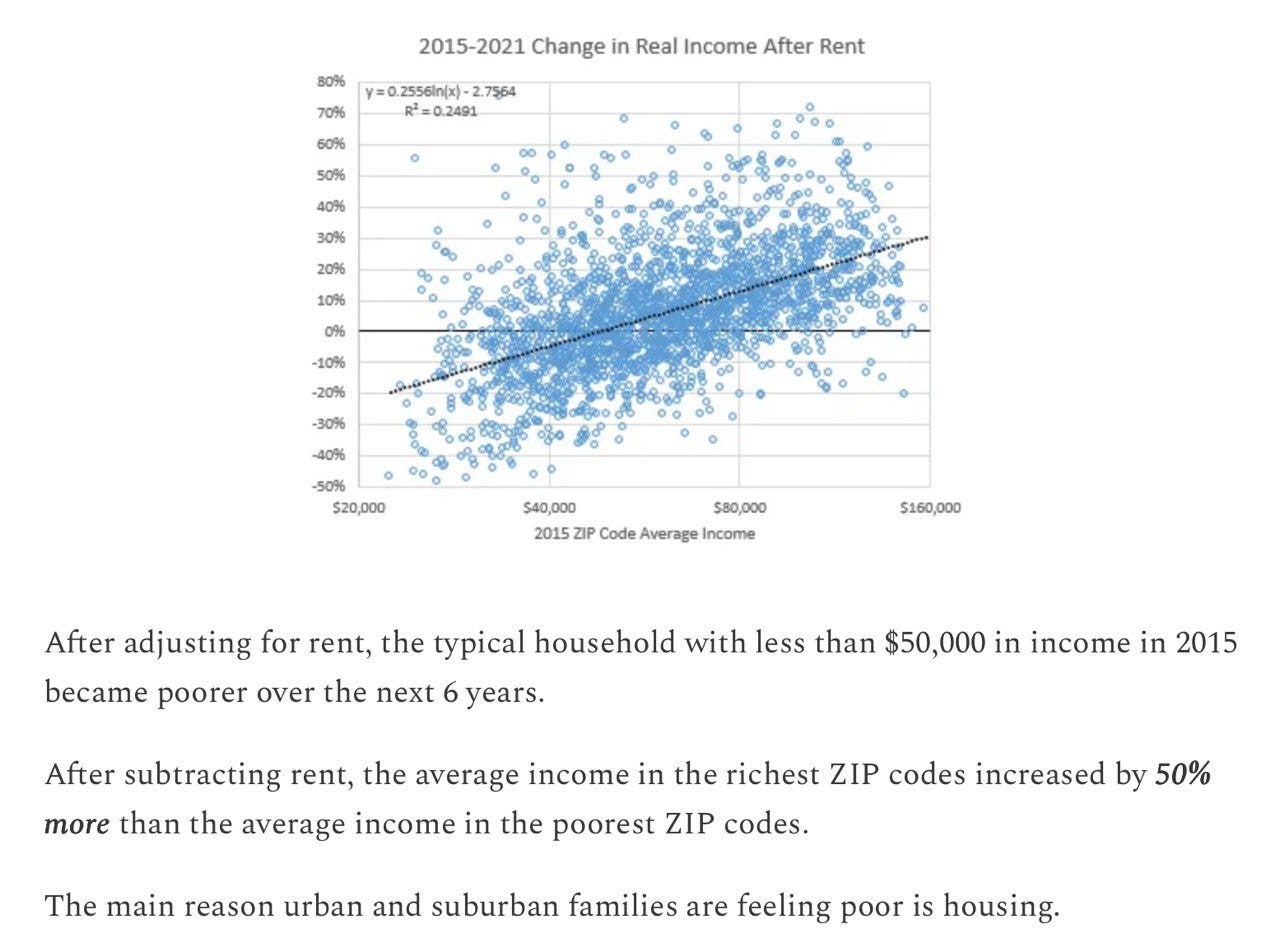

Immigration can also degrade people’s locality-based social capital.2 It can suppress wages and productivity growth through capital becoming relatively more scarce than labour. Immigration also directly immiserates people when population grows faster than housing supply, driving up rents.

Having lots of non-voting housing market entrants encourages restrictive zoning laws, to increase the tax revenue from, and the value of, land. Driving up land values increases infrastructure costs and undermines the tax revenue benefit of providing infrastructure. Social fracturing makes it harder to get things built. It manifests as the common public policy habit of reducing supply (shielding incumbent producers) while increasing demand (by “helping” consumers).

Moreover, the notion that institutions and organisations operate independently of the culture of people in them is flatly wrong. The work of Kenneth Pollack, from his PhD dissertation to Armies of Sand (2019), demonstrates that vividly.

People are not utility-maximising, complete-rationality, socially-interchangeable widgets. They are agents of bounded rationality with persistent cultures pursuing different bundles of life-strategies and they have maps of meaning.

It turns out—especially if migrants are from highly clannish cultures that have been marrying their cousins for 1400 years, and are generally low skill—they can be a net drain on the fisc. Making the fiscal situation of one’s welfare state worse via immigration policies seems an act of remarkable fiscal incompetence on the part of Western European states. But economists treating people as interchangeable social widgets provides cover for such policy incompetence.

Moreover, it is not in the interest of the welfare state apparat to solve or reduce social dysfunction but to sustain and nurture it. This increases its access to resources and the salience of given policy areas. This is dysfunctional social selection, remembering that we Homo sapiens are capable of the required levels of moralised self-deception to carry it off.

The policy point of neoliberalism was to create fiscally-sustainable welfare states. False claims about immigrants and immigration; a narrow market-or-state policy binary; failures to grapple with the flaws of bureaucracy; and ludicrous over-investment in higher education—which, among other effects, has meant that cultural conflicts generated out of toxic academic status games regularly overwhelm needed attention to economic policy—have led to its decay.

The neoliberal elevation of efficiency over economic—and other forms of—resilience, including resilience-through-connections, creates increasing points of vulnerability in social and economic systems. All this has led working-class voters to shift towards populist parties that are willing to elevate citizenship—and the security of common heritage—over the corrosive effects of immigration and cultural assault. Anti-elitism makes perfect sense when the elites are, operationally, out to get you.

The rise of national populism is an expression of the failures, and decay of, the neoliberal policy regime. Unfortunately, there’s no well-developed replacement policy regime on offer.

Economists, with some honourable exceptions, are rendered largely useless by their refusal to admit that anything is wrong in their Empire of Theory. Hence we see the UK Treasury sticking with an immigration economic model that is clearly false. As former UK PM Liz Truss notes, this is intertwined with a globalising moral universalism.

The universities are mostly worse than useless, dominated as they increasingly are by toxic zealotry wedded to the delusional falsities of blank slate anthropology.

The intellectual resources available to national populists are limited and suffer from the general collapse of trust in expertise. This collapse is connected to how blank slate delusions have achieved normative dominance among Western elites.

Such intellectual resources as national populists do have are focused far more on general critique of the neoliberal policy regime, not the painstaking work of policy development.

Continuing social democratic decay

The apparatus of the social democratic state did not go away. It did, however, pathologise. It metastasised. Minnesota is providing us with an example of the social democratic state in its metastasised form.

The neoliberal policy regime did not cut back on the size of the welfare state apparatus nor the scale and reach of the administrative state. In some ways, it aided both by elevating technocratic policy claims. Mastery of the correct Theory gave one the keys to the public policy kingdom.

Alas, technocracy typically presumes way more knowledge than is actually held by the technocrats; greatly narrows the consideration of trade-offs; and skirts (or worse) accountability issues. It means either pretending one is not making such trade-offs; being very narrow in your consideration of trade-offs; or making trade-offs that do not bear much public scrutiny.

Both the welfare state apparatus and that of the administrative state rely on the great advantage of bureaucracy—it regularises administration. This is no small advantage, which is why bureaucracy is used so much.

Alas, bureaucracy also comes with various pathologies that tend to get worse over time. On this point, it’s worth considering some Chinese history. It was China that pioneered the use of examinations to select and appoint officials by testing for cognitive capacity. While some form of this dates back to the Warring States period (475-221BC), it reached full flower with the keju imperial examinations introduced by the first Emperor of the Sui Dynasty (r. 581-604). As it was not abolished until 1905, we have 1300 years of historical experience to consider (apart from its suspension during the Yuan Dynasty).

The only European polity to replicate a Chinese imperial dynastic collapse was the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. Like the imperial Chinese dynasties, it was a bureaucratic autocracy on imperial scale. To add to the similarities, the resource-consuming and authority-expanding imperial bureaucracy strangled the urban self-government that had made the preceding Principate a more capable state.

The keju directed the human capital of China overwhelmingly towards the service of the Emperor. This helped along China’s loss of technological dominance. It encouraged its elite to develop what became a crippling lack of curiosity about the outside—physical, mechanical or commercial—world.

Over time, the keju became more and more focused on an inward-looking Confucianism, and mastering its complexities provided a clear selection device. In our universities, the inward-status games of Theory increasingly disconnected from reality display the same dynamic. This extends to open attack on the scientific method, seeking to subordinate them to Theory’s moralised status games.

The keju also selected for capacity not character. While Confucianism attempted to encourage good character, it was not robust enough as an ethical system to do so in a systematic way. Hence, over time, there was selection within the imperial bureaucracy for capable Machiavellians. It had no equivalent of the duel of honour that provided early modern Europe with a character test.

So, across each imperial Chinese dynasty, bureaucratic pathologies mounted. The bureaucratic tendency to accrue resources to itself, to become more corrupt via the sale of official discretions, to become more focused on internal power and status games, to suppress alternative means of information and organisation, to avoid the complexities of competence, to find ways to frustrate oversight and accountability—all increased as each dynasty aged.3

We can absolutely see these patterns across the developed democracies. Minnesota just allows us to see them in particularly florid form, with added cultural dysfunction. We can see Minnesota Scandinavians being exploited by Somali immigrants in much the same way actual Scandinavians in Sweden have been.

Aspects of Scandinavian culture may have aggravated the problem, although the US has not reached the point Sweden has of paying immigrants to go away.

Well-structured institutions require that their rules and norms be enforced and followed. It is easier to enforce the rules of institutions when people’s culture is congruent with norms than when they are very much not. What we are seeing across the West is elites who are not willing to enforce the rules and norms that make Western institutions functional.

So, the leavings of the social democratic policy regime are metastasising in ways that bureaucratic governance always does. Overweening bureaucracy is not merely an enemy of efficiency—though it is that. It consumes the resilience of its social order by suppressing, atrophying or replacing other social mechanisms. The “demon in democracy”—democracy’s tendency to reduce everything to a single pattern of legitimacy—aggravates this.

What we see again and again is, if there’s a choice between enforcing the norms and rules on which institutions were founded, or failing to do so under the cover of new, socially imperial, moral projects, Western officials and bureaucracies choose the latter. That creates “skin suit” institutions—institutions that claim legitimacy on the basis of what they pretend to be about (or once were about), but increasingly aren’t. This is what cultural collapse looks like.

The continuing normative dominance of blank slate delusions due to Western elites being addicted to status games makes it hard to even begin to discuss where to go from here. A general critique of current failures and problems is not a policy program. The post-liberals are not only a policy-free zone, they’re often innumerate as well.

Both the postwar policy regimes are dying. Yet it is not at all clear that any useful replacement is struggling to be born.

There are two longstanding stupid arguments about Hitler and the Nazis. First, Was Hitler a socialist? Yes, of course he was. He said so, he argued in socialist ways, he did socialist things and stated that he intended to do more of them after Final Victory. Secondly, Was Hitler right wing? Yes, of course he was. He was overtly committed to inequality, militarism, and hierarchy in a way left-wing folk are just not. (Yes, there is an enormous gulf between the equalisers and those to be equalised, but left-rhetoric and self-image is extremely equalitarian.) Adding a third stupid argument—Hitler’s methods provide some sort of solution—does not represent an intellectual advance.

A 2012 study, co-authored by someone since honoured with a Nobel Memorial in Economics, manages to shoe-horn in a term—compositional amenity—as a belittling “explanation” of its results while completely failing to notice that what folk covered by the study were actually complaining about was the degrading/dilution of their local social capital (a term that appears nowhere in the paper). But there are few things that are more appealing to contemporary academe than sneering at the concerns of working class folk; especially working class men, especially about immigration. Conversely, this 2010 study (published in 2013) found that strong local social capital led to greater political accountability. The appeal of immigration—and of favour-divide-and-dominate identity politics—to the political class thus becomes less surprising.

The pacification that Imperial dynasties achieved led to growth in population that would eventually butt up against the constraints of resources and technology, leading to shrinking social niches, more onerous taxes, and aggravated banditry. This interacted destructively with increased competition among the ever-expanding number of elite aspirants for elite positions that did not increase commensurately in size. These patterns aggravated the effect of bureaucratic pathologies increasing over time. Some version of these patterns was experienced repeatedly across states and civilisations. The Chinese version was particularly intense due to elite polygyny and its reliance on a command-and-control bureaucracy.

References

Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano, ‘Culture and Institutions,’ Journal of Economic Literature, 2015, 53(4), 898–944. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.53.4.898

Plamen Akaliyski, Vivian L. Vignoles, Christian Welzel, & Michael Minkov, ‘Individualism–collectivism: Reconstructing Hofstede’s dimension of cultural differences,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (2025). Advance online publication. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2027-01517-001.html

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Prey: Immigration, Islam, and the Erosion of Women’s Rights, HarperCollins, 2021.

Douglas Allen, The Institutional Revolution: Measurement and the Economic Emergence of the Modern World, University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Jan van den Beek, Hans Roodenburg, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, ‘Borderless Welfare State - The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances,’ 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371951423_Borderless_Welfare_State_-_The_Consequences_of_Immigration_for_Public_Finances

Jan van de Beek, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, Hans Roodenburg, The Long-Term Fiscal Impact of Immigrants in the Netherlands, Differentiated by Motive, Source Region and Generation, IZA DP No. 17569, December 2024. https://docs.iza.org/dp17569

Abdulbari Bener, Ramzi R. Mohammad, ‘Global distribution of consanguinity and their impact on complex diseases: Genetic disorders from an endogamous population,’ The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 18 (2017) 315–320. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110863017300174

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Christopher Boehm, ‘Egalitarian Behavior and Reverse Dominance Hierarchy,’ Current Anthropology, Vol. 34, No.3. (Jun., 1993), 227-254 (with Comments by Harold B. Barclay; Robert Knox Dentan; Marie-Claude Dupre; Jonathan D. Hill; Susan Kent; Bruce M. Knauft; Keith F. Otterbein; Steve Rayner and Reply by Christopher Boehm). https://lust-for-life.org/Lust-For-Life/_Textual/ChristopherBoehm_EgalitarianBehaviorAndReverseDominanceHierarchy_1993_29pp/ChristopherBoehm_EgalitarianBehaviorAndReverseDominanceHierarchy_1993_29pp.pdf

George Borjas, ‘Immigration and the American Worker: A Review of the Academic Literature,’ Center for Immigration Studies, April 2013. https://cis.org/Report/Immigration-and-American-Worker

George J. Borjas, We Wanted Workers: Unraveling the Immigration Narrative, W.W.Norton, 2016.

Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith, Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Migration, First Second, 2019.

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018.

Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira, Stefanie Stantcheva, ‘Zero-Sum Thinking And The Roots Of Us Political Differences,’ NBER Working Paper 31688, September 2023, Revised April 2025. http://www.nber.org/papers/w31688

Michael A. Clemens, ‘Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 25, Number 3, Summer 2011, 83–106. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.25.3.83

Ronald Coase & Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

European Commission, Projecting The Net Fiscal Impact Of Immigration In The EU, EU Science Hub, 2020. https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/projecting-net-fiscal-impact-immigration-eu_en

Mohd Fareed and Mohammad Afzal, ‘Genetics of consanguinity and inbreeding in health and disease,’ Annals Of Human Biology, 2017 Vol. 44, No. 2, 99–107. https://www.academia.edu/33934871/Genetics_of_consanguinity_and_inbreeding_in_health_and_disease

Milton Friedman, ‘The role of monetary policy,’ American Economic Review, 58(1), 1968 (March), 1-17. https://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/58.1.1-17.pdf

Adam K. Frost, Zeren Li, ‘Markets under Mao: Measuring Underground Activity in the Early PRC,’ The China Quarterly, 2023, 1–20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/china-quarterly/article/markets-under-mao-measuring-underground-activity-in-the-early-prc/FCED40169CCA6DEEF21B48012BC4D38C

Etienne Gilson, The Unity of Philosophical Experience, Ignatius Press, [1937] 1964.

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Ryan James Girdusky and Harlan Hill, They’re Not Listening: How the Elites Created the National Populist Revolution, Bombardier Books, 2020.

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

Mark Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233. https://www.csc2.ncsu.edu/faculty/mpsingh/local/Social/f15/wrap/readings/Granovetter-revisited.pdf

Laurenz Guenther, ‘Political Representation Gaps and Populism,’ February 3, 2025. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4230288

M.F. Hansen, M.L. Schultz-Nielsen,& T. Tranæs, ‘The fiscal impact of immigration to welfare states of the Scandinavian type,’ Journal of Population Economics, 30, 925–952 (2017), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-017-0636-1

Oliver Heath, ‘Policy Alienation, Social Alienation and Working-Class Abstention in Britain, 1964–2010,’ British Journal of Political Science, 48(4), (2016), 1053–1073. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/70E409B4E2274FAE7844449B95DA0EBB/S0007123416000272a.pdf/div-class-title-policy-alienation-social-alienation-and-working-class-abstention-in-britain-1964-2010-div.pdf

Yasheng Huang, The Rise and Fall of the East: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success, and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline, Yale University Press, 2023.

Garett Jones, ‘Measuring the Sacrifice of Open Borders,’ George Mason University, November 2019. http://digamoo.free.fr/garettjones2019.pdf

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Frank H. Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Cosimo, [1921] 2005.

Katherine J. Latham, ‘Human Health and the Neolithic Revolution: an Overview of Impacts of the Agricultural Transition on Oral Health, Epidemiology, and the Human Body,’ Nebraska Anthropologist, 2013, 187, 95-102. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/187/

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Ryszard Legutko, (trans. Teresa Adelson), The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies, Encounter Books, 2016.

Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Gang Scandal, New English Review Press, 2016.

Tommaso Nannicini, Andrea Stella, Guido Tabellini, and Ugo Troiano, ‘Social Capital and Political Accountability,’ American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2013, 5 (2): 222–50. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.5.2.222

Debin Ma, ‘Rock, scissors, paper: the problem of incentives and information in traditional Chinese state and the origin of Great Divergence,’ Economic History Working Papers 37569, London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Economic History, 2011. https://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/WorkingPapers/Economic-History/2011/WP152.pdf

Debin Ma & Jared Rubin, ‘The Paradox of Power: Principal-agent problems and administrative capacity in Imperial China (and other absolutist regimes),’ Journal of Comparative Economics, (2019), 47(2), 277-294. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/esi_working_papers/212/

Robert Neuworth, The Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Pantheon Books, 2011.

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

R.R.Reno, Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West, Regnery Gateway, 2019.

Dani Rodrik, ‘Feasible Globalizations,’ NBER Working Paper, 9129, September 2002.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w9129

Jonathan F. Schulz, Duman Bahrami-Rad, Jonathan P. Beauchamp, and Joseph Henrich, ‘The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation.’ Science 366, no. 6466 (2019): eaau5141. https://web.ics.purdue.edu/~drkelly/SchulzHenrichetalTheChurchIntensiveKinshipGlobaPsychologicalVariation2019.pdf

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Polygamy, the Commodification of Women, and Underdevelopment,’ Social Science History (2021), 46(1):1-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354584406_Polygamy_the_Commodification_of_Women_and_Underdevelopment

David Ramsay Steele, From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation, Open Court, 1999.

David Sun, ‘Arctic instincts? The Late Pleistocene Arctic origins of East Asian psychology,’ Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, Online First Publication, March 3, 2025. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2025-88410-001.html

Tuan-Hwee Sng, ‘Size and dynastic decline: The principal-agent problem in late imperial China, 1700–1850,’ Explorations in Economic History, Volume 54, 2014, 107-127. https://conference.nber.org/confer/2011/CE11/Sng.pdf

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

United Nations, Replacement Migration: Is it A Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?, Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs United Nations Secretariat, 21 March 2000. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd-egm_200010_un_2001_replacementmigration.pdf

Yuhua Wang, The Rise and Fall of Imperial China: The Social Origins of State Development, Princeton University Press, 2022.

Richard W. Wrangham, ‘Two types of aggression in human evolution,’ PNAS January 9, 2018, Vol.115, No.2, 245–253. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1713611115

Xueguang Zhou, The Logic of Governance in China: An Organizational Approach, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Fei Xiaotong, From the Soil: the Foundations of Chinese Society, trans, with an introduction and epilogue by Gary G. Hamilton and Wang Zheng, University of California Press, 1992.

Chenggang Xu, ‘The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development’, Journal of Economic Literature, 2011, 49:4, 1076–1151. https://hub.hku.hk/bitstream/10722/153452/2/Content.pdf

I very much like how you note the problems start with the conflict between Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau (though he remains un-named); perhaps the biggest problem is that we're still arguing about which of them is right, when really none of them are up to the challenges we live with now.

Absolutely magnificent on first reading and I am confident it will improve each time I visit it.

Featuring Sargon, Niall and Marc Andreessen no less!

You two are spoiling us, more please.