The Revolt of the Somewheres: II

The politics of the institutionally alienated and culturally repressed

This is the thirty-third piece in Lorenzo Warby’s series of essays on the strange and disorienting times in which we live.

This article can be adumbrated thusly: alienated electorates often evince extraordinary loyalty to deeply flawed political entrepreneurs—for explicable if not good reasons.

The publication schedule and links to all Lorenzo’s essays are available here.

Do remember, my Substack is free for everyone. Only contribute if you fancy. If you put your hands in your pocket, money goes into Lorenzo’s pocket.

However, paid subscribers do get exclusive, unrecorded Chatham House Zoom calls with both Lorenzo and me. We held the first of these last month, and there will be another one this month.

Social commentator David Goodhart has usefully identified two broad groups in modern developed democracies.

About half the population in modern developed democracies are (on average) less educated Somewheres, whose identity and social connections are very much bound up in a local community where they are born, marry, work, raise children and die. Around a quarter of the population are (on average) highly educated—and mobile—Anywheres whose networks are not based in a local community.

The previous essay in this series explored national populism in older Western democracies (dynamics in Eastern Europe and elsewhere have significant differences) as a revolt of the Somewheres.

Once you see the Anywheres/Somewheres division, it becomes hard to un-see; forms of it reach deep into history. It is precisely the Somewhere patterns of repeated local marriage and highly localised lives and connections that create and sustain ethnicities: that is, locality-based dialects, folkways and genetic clusterings.

Most aristocracies are Anywheres: much of the Russian aristocracy, for example, was not Russian in its origins. Academics—particularly in the Anglosphere—tend to be Anywheres. Anywheres not only dominate written sources from the past, they dominate our interrogation of the past.

Anywhere domination and Somewhere alienation

In most contemporary Western societies, Anywheres also dominate bureaucracies, the media, non-profits, and lobbyists. They dominate the mainstream political Parties: the politicians, staffers, and Party activists are typically Anywheres. Public debate is overwhelmingly by and between Anywheres and about Anywhere concerns.

Journalism used to be pervaded, even dominated, by jobbing Somewheres. Often working-class lads (and some lasses) made good. Whatever the power of newspaper owners, mass market newspapers were mostly Somewheres talking to Somewheres.

As university credentialism advanced, newspapers (and the media more broadly) over time became Anywheres talking to Anywheres. In accordance with the modern university’s capacity to screw anything up, increasingly toxic status-and-social-leverage games have proliferated within media and its consumption. These are sabotaging the capacity of modern societies to talk to themselves.

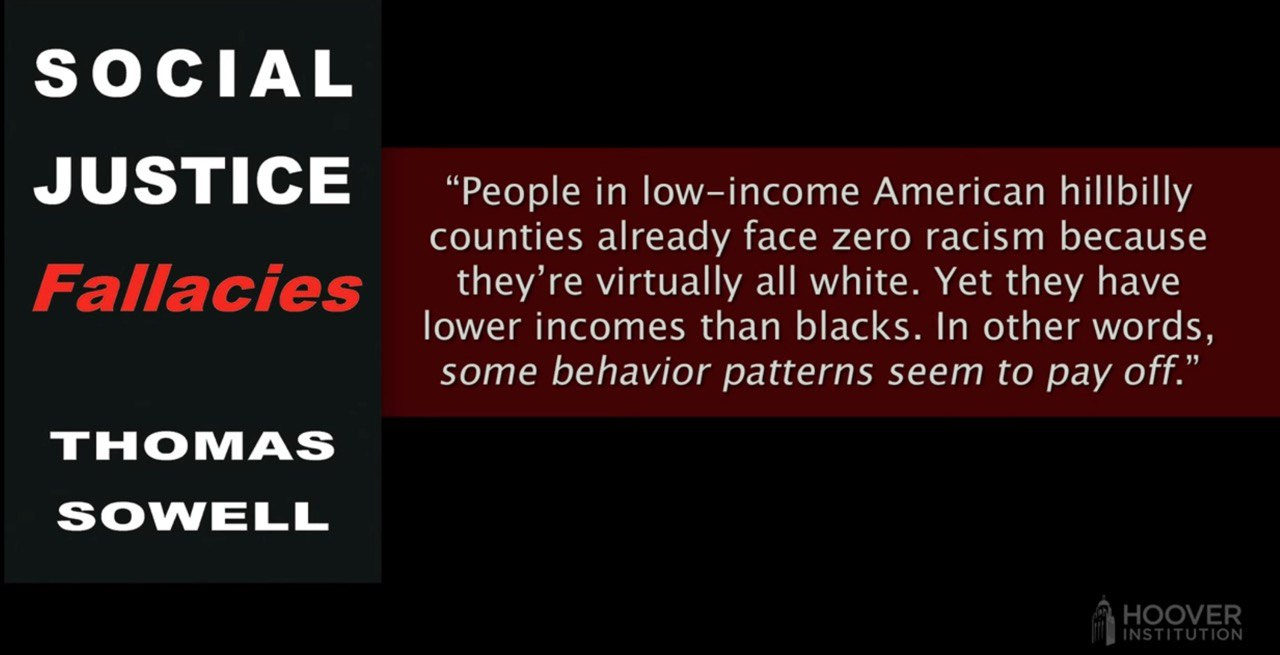

Journalism became yet another profession intellectually and morally corrupted by mountains-of-bullshit built on molehills-of-truth Theory. Theory’s moralising analytical framings distort the ability to understand patterns of social action. Differences in outcomes between groups become “oppression” and bigotry.

Any notion of service to the wider citizenry, or their heritage, is undermined. The wider citizenry is cast—in Theory’s morality-plays—as either human clay to be moulded by their moral and cognitive “betters” or as “deplorable” human dross that stand in the way of such moulding by the righteous moral and cognitive elite.

One does not serve such a citizenry, still less respect their heritage. One seeks to mould them to the proper understanding of events. Such shared senses of superior understanding become embedded in mutually supporting status and social-leverage strategies. Remember—given our capacity for strategic self-deception—something can be both a manifestation of moral conviction and a status and social-leverage strategy.

Elite media has become Anywhere Pravda, pushing social-leverage and status strategy-supporting narratives. Such media has become what you read to give the appearance of being informed while learning what it’s currently acceptable to say. “Fact-checking” provides narrative confirmation while also flattering readers about the superiority of their media-consumption choices.

This has a strong class element to it. Much of the defund the police/anti-police activism in the US has been moralised elite resentment against working-class police officers having authority over them. There is a great deal of class-condescension, even contempt, when Anywhere academics greatly over-ascribe racism to explain patterns of Somewhere behaviour.

If someone who achieves public prominence starts talking to Somewheres—rather than at or over them—they are likely to inspire considerable loyalty from people starved of public representation for their concerns. Such a political entrepreneur is also likely to inspire fury from the Anywheres, who want politics to remain their game: a dominance enforced by policing the legitimacy of discourse. Donald Trump is the most salient (but hardly only) exemplar of this pattern and response.

If one of the Anywhere-dominated political parties does manage to scoop up a sudden surge of Somewhere votes by talking to Somewhere concerns, the Anywhere institutional domination of bureaucracy, media, nonprofits—and the Party organisation itself—is likely to lead to a reversion to Anywhere dominance of politics in government. This is especially so as politicians spend so much time responding to Anywhere media (and social media). Such reversion to Anywhere framing and preferences is likely to be viewed by Somewhere voters as a betrayal (as, of course, it is). The Tories in the UK are currently experiencing this effect.

Alternatively, in a Party shifting towards garnering more Somewhere voters without serving their concerns, one sees a retreat into rhetoric, even political theatre, that seeks to hold onto Somewhere votes despite not serving Somewhere interests or concerns. This rhetoric and political theatre becomes increasingly frantic the greater the tension between Somewhere voters and the Anywhere political and donor class becomes. The US Republican Party epitomises this pattern, and has since well before Donald Trump’s nomination.

A hard question directed at conventional conservative politicians: what have you conserved? —is indicative of this Anywhere versus Somewhere split. In the US, the people and networks derided as Conservative Inc.—folk who seek to lose gracefully while making the right noises—are Anywhere conservatives.

Trump’s “stop the steal” is a classic literally-false-but-metaphorically-true myth. No, the 2020 Presidential election was not stolen. But his entire Presidency was beset by an Anywhere revolt against Somewhere concerns reaching the Presidency. Hence there was a systematic campaign to deny the legitimacy of his Electoral College win, his Presidency, and any implementation of Somewhere concerns. All of which gives his “stop the steal/stolen election” rhetoric (disgraceful) mythic resonance.

The operative paradigm is that as long as enough Anywheres agree, all is fine. The delusion that geopolitics—“old-fashioned” concerns about national security can be supplanted—has helped this push. It reduces further the need to bargain directly with Somewheres.

Struggles between states have been a great driver of broadening political bargaining to mobilise social support: this is a recurring theme in Western history. The less Anywhere elites believe that they need the Somewheres—and especially the consent of the Somewheres—the less incentive they have to seriously bargain with them when they can just practice the non-electoral politics of institutional capture. These politics extending, of course, to campaigns against “disinformation”: functionally defined as anything that contradicts Anywhere social-leverage and status narratives.

Connections and promises

Much of European history since the middle of the medieval era has been a pattern of expanding political bargaining, something the non-electoral politics of institutional capture reverses. One of the more striking European patterns is that monarchy and parliamentarianism tend to be mutually supporting. The European polities with the most consistent Parliamentary traditions (the Atlantic littoral of North-Western Europe) are those most likely to be monarchies.

The basic pattern is that monarchies—outside the former Soviet bloc—that kept bargains they made, survived. Those that did not, failed.

Surviving monarchies that are not micro-states—Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, Monaco—are quite likely to be Protestant: UK, Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Sweden. Only Belgium—which probably needs the monarchy to survive as a unified state given Walloon-Flemish tensions—and Spain (a restoration) are Catholic monarchies that are not micro-states.1

Protestantism leaves the individual naked before God: this may aid bargain-keeping. Edicts of religious toleration in Protestant Europe tended to stick, those in Catholic Europe tended not to be worth the paper they were printed on. There are differences in economic behaviour between Protestant and Catholics. Protestants tend to be more future-directed than Catholics, which affects financial outcomes.

Even though Protestantism valorised direct access to Scripture, and the individual as naked before God, the key political effect of Protestantism was not to increase individualism. Atomised individuals provide no basis for resisting central authority. Much more important politically was changing the priest into a pastor—an instrument of the congregation. This strengthened local connections, thereby giving extra oomph to political bargaining.

Parliaments enabled coalitions of connected localities to have authority over legislating and spending. It was an intense congregationalism that gave the culture of New England its remarkable political and social characteristics—including the most successful social uplift in history.2

The collapse of participation in religious congregations has created a vacuum in local connections that produces more atomised societies. Such atomisation is aggravated by the welfare state’s tendency to replace other forms of social action, or simply make them more difficult. Various forms of expanded liability and certification discourage volunteering, for example.

We live in societies that are far more atomised than they used to be, with startlingly novel information environments. There are reasons for caution in using past patterns as grounds for expectations about likely futures. Even though some of those past analogies—e.g. the printing press, a new information technology disrupting the public sphere, leading to the witch-craze and the Wars of Religion—are rather alarming.

On migration

Migration both exemplifies the decline in local-connection political bargaining and balkanises the demos. Migration to the US, UK and in Western Europe is on a level and of a type that lacks popular support, and is clearly polarising various societies around provincial-metropolitan divides.

Where border control is not enforced, voters are explicitly stripped of any say about their society’s future direction. It’s clear much of the explicit or implicit opposition to effective border control is structured to have that effect.

The economic benefits of migration overwhelmingly go to the migrants. The rest goes to the domestic holders of capital (including human capital): so, largely to Anywheres. And they seek to dominate discourse on this issue, as on others, through control of legitimacy in discourse.

Mass migration that does not select for high human-capital migrants systematically advantages the holders of capital (and land) over labour. Though, as Australia demonstrates, migration that selects for levels of capital—especially human capital—higher among migrants than the domestic average can ameliorate the effect by not increasing the relative scarcity of capital compared to labour.

Australia’s compulsory voting forces politicians to pay more attention to Somewhere concerns. Elsewhere, increasing political alienation among Somewheres leads them to exit from voting.

As for studies of the effect of migration on labour, some studies find a (very small) net gain others a (very small) net loss from migration. These studies almost invariably greatly understate the cost of migration to labour. They treat migration in terms of patterns of exchange without looking at the wider social and economic structures in which those exchanges are embedded.3

For instance, not considering the Baumol effect, whereby increases in productivity lifts wages down the productivity chain as “adjacent” wages have to rise to attract workers. Hairdressers are paid way more in 2023 than they were in 1963—despite a lack of any increase in the productivity of hairdressers. Without such increases, no-one puts in the effort to become a hairdresser.

If you bring in lots of low human-capital migrants, that suppresses the Baumol effect at the low-skill end of the labour market. Given that wages are “sticky”, it’s hard for migration to cut wages, but it can certainly suppress wage rises.

The basic pattern is that globalisation of supply-chains suppresses the Baumol effect in developed democracies for internationally-traded goods and services while mass low-skill migration suppresses the Baumol effect for non-traded goods and services.

As I’ve noted previously, analysis of migration in terms of patterns of exchange does not take into account the break up of locality-based social capital by large influxes of people without local connections. Nor does it usually consider positional goods: supply-rationed status/amenity goods where much of the benefit is that you have it and others do not.

Positional and quasi-positional goods include access to infrastructure (as it takes time to build extra infrastructure and it is not always practicable to do so) creating crowding and congestion effects; access to land (which is often turned into a positional good via zoning and/or zoning is used to protect existing locational positional goods), raising shelter costs (often quite dramatically over time); access to politics and to policy attention.4

The last effects can be particularly intense when complaints about the effect of migration are de-legitimised or explicitly suppressed, often by use of ever-shifting linguistic taboos. Migration has become an issue where the pattern of required affirmations, not noticings and stigmatising wrongful noticing has been particularly strong, all part of Anywhere discourse policing.

Like any imperial/colonial/domination structure, Anywhere elites benefit from breaking up and balkanising the Somewhere demos. There has been use of mass migration to break-up working-class communities, to divide the demos into competing groups, to devalue citizenship, and to de-legitimise cultural and institutional heritage. The institutional politics of Diversity-Inclusion-Equity—which divides people into identity groups and then creates moralised hierarchies thereof—fits into this pattern.

Asymmetric multiculturalism is particularly useful in supporting these effects: e.g. public-sector support for Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu etc. festivals is “multiculturalism”; support for Christian events is not—indeed, is taken to be anti-multiculturalism. All this feeds into progressivist social imperialism denigrating the cultural heritage of their social “lessers”.

The general pattern is to balkanise the demos to play favour-and-dominate games. Something that migrants, indigenous folk, and other racial minorities can be used to justify.

Differential policing by locality also aids such balkanisation. This is very clear in the Americas, where the ex-slave diaspora and under-policing of fiscal-sink localities—localities that represent net fiscal loss for governments—creates different crime rates by group-associated localities.

We can also see it operating in France’s migrant-dominated banlieue, where police largely operate as an occupying alien force: there is a long French history of treating the underclass badly.

The demand that the Anywhere ownership of morality be universally respected undermines institutions providing sanctuary against these pressures. We can see this very clearly with the Transcult, which is being used, quite systematically, to undermine parental authority. The repeated claim—increasingly expressed in legislation—is that children cannot trust the parents that gave birth to them and raised them, but they can trust organs of the state who have “caring” expertise in an appropriate Theory.

As Anywheres own morality, any opposition to moralised social strategies is against morality, so illegitimate. “Obviously” there can be no bargaining with the morally illegitimate.

Moreover, the fable of progressive innocence—including the claim that cultural imperialism and denigration of existing cultural heritage is entirely worthy—entails that their policies do not have bad outcomes. Any bad outcomes can only come from not doing said policies properly, perhaps due to sabotage by malevolent actors. This pattern of protection and denial is one that Marxists have long used.

Any political entrepreneur who breaks through the Anywhere cartel is likely to be some mixture of unusually egotistical, or unusually ideologically alienated, in order to be willing to endure the angry crap that predictably comes his way. Hostility to considering the downsides of migration drives discussion of the issue to the politically alienated or other outliers. There are likely to be plenty of flaws in such a political entrepreneur, flaws at which Anywhere critics can point.

Meanwhile, the Somewhere supporters of such a political entrepreneur are likely to see attacks as vindication that this person—speaking to their concerns as no one else does—is, veritably, their champion. This generates a polarising spiral of mutual incomprehension and contempt, a polarising spiral aggravated by social media algorithms and by a Pravda model media that systematically sabotages the ability of society to talk to itself.

Moreover, telling Somewheres to trust the institutions that clearly and increasingly do not respect them—and do not serve their interests—is not an appealing strategy. On the contrary, the pose of being a champion who will go over the top of institutions that increasingly obviously neither respect nor serve them is going to have profound appeal—however much said champion is not going to deliver.

The next essay begins the exploration of modern Western civilisation as a civilisation of broken feedbacks.

—

References

Books

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Prey: Immigration, Islam, and the Erosion of Women’s Rights, HarperCollins, 2021.

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018.

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989], 1994.

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

Eric Kaufmann, Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities, Penguin, 2018.

Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Gang Scandal, New English Review Press, 2016.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Stephanie Muravchik, Jon A. Shields, Trump’s Democrats, Brookings Institution Press, 2020.

Vivek Ramaswamy, Woke Inc: Inside the Social Justice Scam, Swift, 2021.

Luke Stanley, Will Tanner, Jenevieve Treadwell, James Blagden, The Kids Aren’t Alright: They 4 Factors Driving A Dangerous Detachment From Democracy. Why young people are detaching from democracy and social norms – and what to do about it, Onward, September 1, 2022.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

Articles, papers, book chapters, podcasts

Abdulbari Bener, Ramzi R. Mohammad, ‘Global distribution of consanguinity and their impact on complex diseases: Genetic disorders from an endogamous population,’ The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 18 (2017) 315–320.

George Borjas, ‘Immigration and the American Worker: A Review of the Academic Literature,’ Center for Immigration Studies, April 2013.

Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´inez-Toledana, Thomas Piketty, ‘Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages In 21 Western Democracies, 1948–2020,’ The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol. 137, 2022, Issue 1, 1-48.

Zach Goldberg, ‘How the Media Led the Great Racial Awakening,’ Tablet, August 05, 2020.

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/media-great-racial-awakening.

Mark Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233.

Ryan Grim, ‘The Elephant in the Zoom,’ The Intercept, June 14 2022.

Rob Henderson, ‘Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class—A Status Update,’ Quillette, 16 Nov 2019.

David C. Lahtia, Bret S. Weinstein, ‘The better angels of our nature: group stability and the evolution of moral tension,’ Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 2005, 47–63.

Stephen Leslie et al, ‘The fine scale genetic structure of the British population,’ Nature 2015 March 19; 519(7543): 309–314.

Jacob Mchangama, ‘The Sordid Origin of Hate-Speech Laws: A tenacious Soviet legacy,’ Hoover Institute, December 1, 2011. https://www.hoover.org/research/sordid-origin-hate-speech-laws.

D. Rozado, R. Hughes, J. Halberstadt, ‘Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with Transformer language models,’ PLoS ONE, 2022 17(10): e0276367.

Manvir Singh, Richard Wrangham & Luke Glowacki, ‘Self-Interest and the Design of Rules,’ Human Nature, August 2017.

Peter Thiel, ‘The Tech Curse,’ Keynote Address, National Conservatism Conference, Miami, Florida, September 11, 2022.

Daniel Williams, ‘The marketplace of rationalizations,’ Economics & Philosophy (2022), 1–25.

Finland and Iceland are the most Protestant republics, followed by Germany and Switzerland. Portugal, France, Italy, Austria, Andorra are all Catholic republics, Greece an Orthodox one.

Folk who would fall into underclass poverty in other societies were essentially shamed into prudent behaviour.

Migrants are not just labour units, they are people: their economic effect operates across the entire range of human interactions in society. So, it includes things such as effect on social capital, congestion effects, crowding out effects (e.g. in politics), and so on.

Robert Fogel points out that mass migration destabilised the American Republic along the fault-line of slavery. Higher migration to the more economically vibrant free States systematically reduced the slave States’ federal representation while leading the new Republican Party to finesse nativism by focusing on opposition to “the Slave Power”.

Migration to the slave States increased the numbers of “masterless men”—free folk systematically disadvantaged by a slave system that raised the price of land while lowering the status and wages of manual labour. The plantation elite’s great fear was an alliance of slaves with “masterless men”, especially as the two groups constantly interacted.

The measures that became Jim Crow—when racialised after Reconstruction—originally evolved to suppress the “masterless men”. Slaves plus masterless men was precisely the alliance that the Republican platform of tariffs, homesteading and anti-slavery threatened to bring about, hence the secession of slave States in response to Lincoln’s election as President.

"Trump’s 'stop the steal' is a classic literally-false-but-metaphorically-true myth. No, the 2020 Presidential election was not stolen."

I understand your point, but I believe you overlook the fact that electoral outcomes can be--and have been--corrupted and suborned under color of law.

This is in fact the very argument that is made by those who oppose voter ID laws on the basis that they "suppress the vote." While a substantial part of that argument is mere bloody-shirtism, what is really in play is the ability to manipulate the outcome by blurring who is actually eligible to vote. This was also at the core of the arguments about mail-in and drop-box ballots during the Late Unpleasantness.

You are certainly correct that the "stop-the-steal" argument lacks nuance...though of course, such nuance as is a part of the argument is flattened out by the media's selective reporting. But it is a fact that there have been several presidential elections in our checkered history that have been marred by what I'll call irregularities, all of which were fully and entirely legal and within the four corners of the Constitution: 1824, 1876, and 1960 come to mind. And of course we have spent nearly a quarter-century listening to certain people re-litigate the outcome of the 2000 election as well.

I realize this issue is not central to your larger point, with which I completely agree. I merely wish to respectfully point out that it is neither a new issue nor one that is limited to demagoguery.

Something to remember is that many of the Anywheres grow out of it. They either decide to go home, or they were always looking for a home, and finally find one. This leads me to believe that when we take our next look at immigration, and how to rerform it, we need a different sort of work visa, for the people who mostly want to see the world, experience the broadening effect of travel, maybe teach others a bit about their home culture, etc.